The Acadian Deportations

The Beginnings

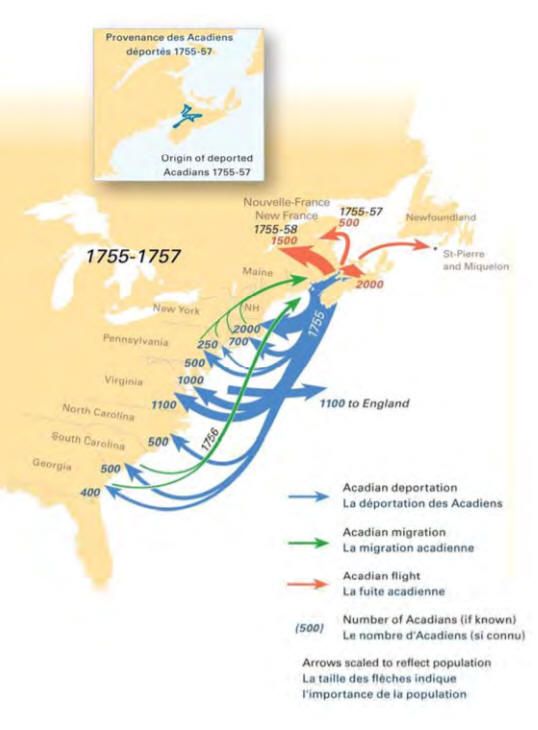

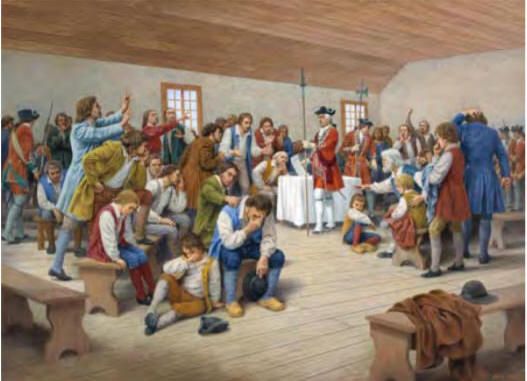

Although the deportation of the Acadians is often considered a singular event spanning eight years, in reality it was two major upheavals with several smaller expulsions and disturbances occurring throughout the eight-year period. On 28 July 1755 Lieutenant Governor Charles Lawrence signed the order passed by his Nova Scotia Colonial Council to deport the Acadians from Nova Scotia. Members of the Council included Charles Morris, John Collier, Mr. Cotterall, Benjamin Green, John Rous, Jonathan Belcher and Richard Bulkeley. In 1754 Jonathan Belcher became the first Chief Justice of the Nova Scotia Supreme Court and in mid-1755 he wrote the official opinion that deporting the Acadians was both authorized and required under the law - a biased and flawed judicial opinion based on the Acadians' refusal to take an unqualified Oath of Allegiance. The maps of the Acadian villages done earlier by Charles Morris, a surveyor, and Morris' plan to surround the Acadian churches were used by Lawrence to initiate the Acadian expulsion.

Lawrence's deportation order was done without the knowledge or authority of the British government including the Lord Commissioners for Trade and Plantations. Furthermore, Lawrence and his Council did not notify the American colonies along the Atlantic seaboard prior to passing the deportation order - despite the fact that the deportation order specifically stated that the Acadians would be sent to these colonies. Only Governor William Shirley of Massachusetts knew of the Acadian deportations in July 1755 because he had worked with Lawrence to ensure that they became a reality. Later, on 11 August 1755 Lawrence sent a circular letter to the governors of the colonies although they did not receive the circular letter prior to the Acadians reaching their colonial shores. Lawrence lost little time implementing his deportation order. On 31 July 1755 he announced his order to arrest Acadians and expel them from Nova Scotia. He then ordered Colonel Robert Monckton to Chignecto and Chepody, Lieutenant Colonel John Winslow to Minas and Cobequid, Captain Alexander Murray to Pigiguit and Major John Hanfield to Annapolis-Royal. They were to capture the Acadians immediately and prepare to send them to the American colonies along the Atlantic seaboard. In addition, to prevent the Acadians from attempting escape or returning to Nova Scotia, these military leaders were to burn churches, houses and other buildings to the ground, destroy crops and confiscate belongings of the Acadians. Although Justice Jonathan Belcher justified the deportations based on the Acadians refusing to take an unqualified Oath of Allegiance, Lawrence and his Council almost certainly considered other reasons also. Without examining how significant each was in their decision, these factors certainly included:

* Acadians refusing to take an unqualified Oath of Allegiance

* A few Acadians taking up arms against the British despite the Acadian claim of neutrality

* The approaching French and Indian War (also called the Seven Years' War; 1756-1763) and the fear that the Acadians would assist the French

* Providing the fertile Acadian farmlands to immigrants from the American colonies

* Fear of the Acadians influencing the Mi'kmaq against the British

* Fear of the large French Catholic population in Nova Scotia in 1755 compared to the small British population (mostly soldiers) at that time

* The strong political organization within the Acadian communities that resisted outside influence

* Frustration of the Nova Scotia leaders with the smart, conniving Acadians

* The Catholicism practiced by the Acadians rather than the Anglican religion of the British

Why were some Acadians deported to the British colonies in America and others deported to France? In the period 1755-1763 Britain owned Nova Scotia. They defeated France in Queen Anne's War (1702-1713) and with the 1713 Treaty of Utrecht received from France the part of Acadia now known as Nova Scotia except for Île Royale (today Cape Breton Island). France retained Île Royale, Île Saint-Jean (today Prince Edward Island) and Saint-Pierre and Miquelon. New Brunswick also remained French although its boundaries were contested for many years. Thus Acadians living in Nova Scotia during 1755-1763 were British citizens and only could be deported to British territory (Britain or its possessions). Acadians living on Île Royale, Île Saint -Jean and New Brunswick during this period were French citizens and had to be exiled to France or its territories.

The Acadians experienced horrible conditions on the deportation ships. They were treated the same on each ship. The crew of the ship feared the Acadians overpowering the crew and overtaking the ship. The Acadians, therefore, were placed in the hole of the ship. The hatch was opened and the Acadians were forced into the bowels of the ship - using a ladder to descend. There was no lighting and no air circulation. Only when the hatch was opened did any light penetrate into the depths of ship. Otherwise, the Acadians lived in almost total darkness. No air circulated in the bowels. Again only when the hatch was opened did even a small stream of fresh air enter the area housing the Acadians. The air quickly became stale and shortly afterwards foul-smelling - the stench almost unbearable. There were no "beds" to sleep on or any place to relax. The Acadians had to sleep on the floor or on any elevated position they could find. All of the ships were overloaded - exceeding the two persons per ton limit. Acadians often had to take turns resting due to lack of space. Occasionally, the crew opened the hatch and allowed a few Acadians at a time topside briefly for fresh air. There were no sanitary facilities in the bowels of the ship. The floor became the "toilet". The stench became horrific after a brief time. Dysentery affected many. Likewise, the rolling seas caused much seasickness. Vomit mixed with the other wastes on the floor. These conditions were perfect for disease and it spread quickly among the Acadians - causing great distress and even death. These were the conditions in which the Acadians had to survive in the hole of the ship - often for two months or more at sea and several weeks after reaching port. How any Acadians survived is truly amazing.

The Bay of Fundy Campaign - First Major Upheaval

By 8 August 1755 the ships to deport the Acadians had been secured - most were contracted from the Boston mercantile firm of Apthrop and Hancock. They were outfitted to hold two persons per ton although nearly every vessel was significantly overloaded during the deportations. By the end of August the ships began arriving in Nova Scotia although only a few at a time. During August and September the British began capturing and imprisoning Acadians throughout Nova Scotia. The British commanders held the captured Acadians at Fort Cumberland (formerly Fort Beauséjour), Fort Lawrence, Annapolis Royal, Fort Edward, the Catholic Church at Grand-Pré as well as Georges Island at Halifax.

By mid-October 1755 the British believed enough ships had arrived in Nova Scotia waters to begin the deportations. Because the British believed Acadians of the Chignecto peninsula (Beaubassin and area) were the most ruthless, the British began exiling them first - sending them to South Carolina and Georgia, the most distant British colonies from Nova Scotia. About 400 of the Acadians were in Fort Beauséjour when the British captured it and many of these held arms. Their claim, backed by the French military, was that they had been forced by the French to take up arms. Still Colonel Monckton used this incident as an excuse to claim the Acadians were not neutral and thus must be deported. Many of these Acadians originally had resided at Beaubassin (which the Mi'kmaq had torched in 1750 under the orders of Abbé LeLoutre) and they had been forced to move north to lands near Fort Beauséjour. Others came from Tintamarre, Wescock, Aulac, Baie-Verte and nearby areas - having escaped Nova Scotia shortly before and resettled in New Brunswick. Many Acadians in New Brunswick escaped the grasp of the British and had fled to more distant outposts in New Brunswick.

On 13 October 1755 eight ships with approximately 1200 Acadians set sail from the Chignecto area for South Carolina (ca. 800 Acadians) and Georgia (ca. 400 Acadians) - over 200 Acadians perished during the voyage of one to two months.

On 27 October 1755 Lt. Colonel Winslow and Capt. Murray loaded the Acadians from Grand-Pré, Pigiguit, Rivière-aux-Canards, Rivière des Habitants, Rivière Gaspareau and nearby areas onto the transports. Fourteen ships set sail that day with approximately 2550 Acadians bound for Maryland (4 ships, ca. 900 Acadians), Pennsylvania (3 ships, ca. 450 Acadians), Virginia (6 ships, ca. 1000 Acadians) and Massachusetts (1 ship, ca. 200 Acadians). Acadians being deported from the Grand-Pré area by Lt. Colonel Winslow embarked at Pointe-aux Boudrot (today's Starrs Point) on the Rivière des Habitants (today's Cornwallis River). The Acadians from the Pigiguit area deported by Capt. Murray embarked at the junction of the Avon River and St Croix River (near today's Windsor). All transports reached their final ports within two to four weeks except one ship going to Virginia that took two months. A furious gale arose in the western Atlantic on November 5th and six of the transports sought safety in the Boston harbor for several days. The Boston authorities inspected the ships and removed several Acadians due to overcrowding.

On 30 November 1755 a sloop departed from Pointe-des-Boudrot with approximately 170 Acadians bound for Connecticut where it arrived on 22 January 1756.

On 13 December 1755 two ships departed from Pointe-des-Boudrot for Massachusetts (ca. 230 Acadians) and Connecticut (ca. 110 Acadians). They both arrived at their assigned ports on 30 January 1756.

On 20 December 1755 two schooners sailed from Pointe-des Boudrot for Massachusetts (ca. 120 Acadians) and Virginia (ca. 110 Acadians). Massachusetts was reached in only six days while the other schooner reached Virginia on 20 January 1756. The Virginia authorities refused to accept the exiled Acadians sent there. After five months on ships and ashore in Virginia, the Acadians were loaded onto new ships and sent to England. Here they were kept in squalid conditions at Bristol, Falmouth (Penryn), Liverpool and Southampton until the end of the Seven Years War in 1763. The surviving Acadians were taken to France.

Acadians detained near Annapolis Royal were taken to Goat Island in the Annapolis River (near the old habitation at Port-Royal) for embarkation. On 27 October 1755 a snow with approximately 320 Acadians left Goat Island for Boston, Massachusetts and arrived there in three weeks. Then on 8 December 1755 five ships loaded with Acadians sailed from Goat Island: two for Connecticut with approximately 600 Acadians, one for New York with about 250 Acadians, one for South Carolina carrying approximately 350 Acadians and one bound for North Carolina with about 230 Acadians. One ship bound for Connecticut arrived in six weeks; however, the second transport for that port was blown off course and took refuge at Antigua before eventually reaching Connecticut in five and one-half months. Over one-third of the Acadians on this ship died from malaria. The ship to New York also was blown off course to Antigua and finally reached New York in about five months. Acadians on the ship to South Carolina reached port there in about five weeks. The snow to North Carolina never reached its destination. Angry Acadians seized the snow off the coast of New York and sailed it back to Rivière St-Jean in the Bay of Fundy. They evaded the British moving deep into New Brunswick with a number of them attempting to walk to Québec - a walk along which many died. One snow with about 250 Acadians in the hole left Goat Island on 13 October 1755 for Connecticut; however, it never reached its destination - likely sinking in the Atlantic with its cargo of Acadians.

Approximately fifty Acadians, almost all closely related to the Guédry family, were captured at Merliguèche (near today's Lunenburg) in September 1755 and imprisoned on Georges Island in Halifax harbor. On 15 November 1755 they were loaded onto a sloop and sent to North Carolina where they arrived on 13 January 1756 - almost certainly at Edenton, North Carolina, a thriving port city on the Albemarle Sound.

From 13 October to 8 December 1755 the British had exiled over 6300 Acadians from Nova Scotia - ridding themselves of a "problem", but creating even greater troubles for the British colonies along the Atlantic and an almost unbelievable upheaval in the lives of so many Acadians. Thus drew to a close on 8 December 1755 the Bay of Fundy Campaign to deport the entire Acadian population from Nova Scotia.

As the tensions between the Acadians and the British grew deeper during the late 1740s and early 1750s, many Acadians fled Nova Scotia for nearby French territories - Île Royale, Île Saint-Jean and New Brunswick primarily. Beginning in 1756 those fleeing to New Brunswick were hunted by the British continuously. Many deaths resulted - both Acadian and British - from the fighting and from the severe winters. Some Acadians evaded the British for several years and moved far north above the falls of the St. John River and settled in Maine and northern New Brunswick. Today they remain a strong, vibrant Acadian community in Aroostook County, Maine and across the St. John River in Madawaska County, New Brunswick. Other Acadians were not so fortunate and, when captured, were imprisoned at Fort Cumberland, Fort Edward and Georges Island. Most were kept in these prisons for the remainder of the French and Indian War.

The Forgotten Acadians - A Smaller Exile

On the 1st of April 1756 a sloop departed from Georges Island with approximately four members of the LeBlanc family and took them to Boston which it reached in two months.For some unexplained reason the British initially made no attempt to capture or deport the Acadians in the Cape Sable area. In early 1756, however, plans changed and two ships left Cape Sable with approximately 175 Acadians from Pobomcoup and other nearby areas. Approximately 100 Acadians disembarked on 28 April 1756 at Manhattan, New York and about 75 Acadians were put ashore on 10 May 1756 at Boston.

These three ships transporting approximately 180 Acadians comprised the small exile of Acadians initially "forgotten" from the Bay of Fundy Campaign.

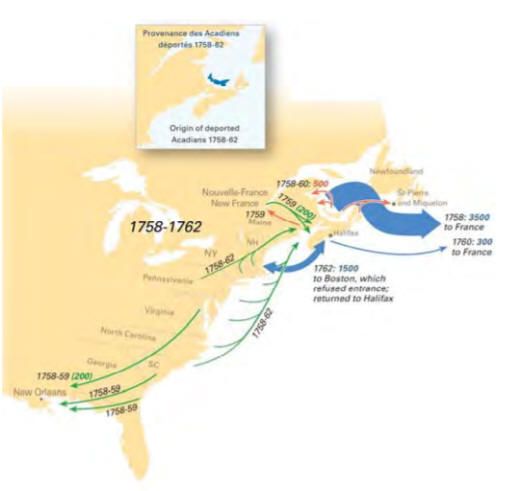

The Islands Campaign - Second Major Upheaval

By the 12th of June 1758 the British under Admiral Boscawen had begun the second siege of the Fortress of Louisbourg on Île Royale. The British earlier had captured the Fortress of Louisbourg from France in 1745 using siege tactics; however, Britain returned the Fortress to French control in 1748 with the Treaty of Aix-la-Chapelle. On 26 July 1758 the French in the Fortress capitulated and the British regained control of Louisbourg and Île Royale. Thus began the second major phase of the British scheme to rid the region of Acadians - deporting Acadians from Île Royale and Île Saint-Jean. These exiles were more brutal and devastating than the earlier Bay of Fundy Campaign with many more Acadians perishing from ships sinking and diseases.Acadians captured on Île Royale and Île Saint-Jean had to be sent to France since these Acadians were living in French territory and thus were French citizens.

The 17th of August 1758 a British force of 500 troops under Lt. Colonel Andrew Rollo landed at Port-la-Joye on Île Saint-Jean and took control of the island. The French surrendered the island with no resistance after learning of the fall of Louisbourg. Immediately the British built Fort Amherst at the site of Port- a-Joye. At the time of surrender there were almost 5000 Acadians on Île Saint-Jean.

Many Acadians on Île Saint-Jean fled across the Northumberland Strait in small boats and French schooners to Miramichi, to other coastal areas of New Brunswick and to Québec. A few went to St. Pierre and Miquelon while others hid in the woods at Malpeque and the Northeast River of Île Saint-Jean. The British captured many others during the latter part of August 1758 and held them at Fort Amherst. At the same time soldiers on Île Royale were rounding up Acadians on that island and bringing them to Louisbourg for exile. Hundreds of Acadians escaped this phase of the deportations by fleeing to the shores of New Brunswick south of the Baie des Chaleurs where Charles Deschamps de Boishebert had refugee camps.

On 31 August 1758 five ships carrying almost 700 Acadians sailed from Fort Amherst to Louisbourg where they arrived on 4 September of that year.

The Islands Campaign of the deportations began on 4 September 1758 when the Duke of Cumberland sailed from Louisbourg with approximately 350 Acadians aboard headed for La Rochelle, France. The next week on the 10th of September two additional ships left Louisbourg with about 600 Acadians bound for La Rochelle. On 27 September 1758 a fourth ship Mary sailed from the Louisbourg harbor with almost 600 Île Saint-Jean Acadians heading to St. Malo, France. It arrived at Spithead, England on 31 October - almost half of the Acadians having died at sea. The survivors were transferred to two other ships and sent to Cherbourg, France where they arrived near the end of November 1758.

Also, in September 1758 four ships sailed from Louisbourg with over 600 Acadians. Three ships (ca. 540 Acadians) were bound for St. Malo, France and one ship (ca. 90 Acadians) was heading to Brest, France. The three ships reached St. Malo on the 1st of November - having lost over 200 Acadians on the voyage and over 40 shortly after arrival. The other ship reached Brest on 26 October 1758 with fifteen Acadians dying at sea and one shortly after arrival.

On 28 October 1758 the approximately 360 inhabitants of the village of Pointe-Prime, Île Saint-Jean were herded onto the Duke William, which sailed first to Chédabouctou Bay near Canso. From there it convoyed with six other ships including the Violet (ca. 400 Acadians) toward St. Malo, France. In late November a violent storm occurred, scattering the convoy of ships. The Duke William and Violet rejoined each other on 10 December. The Violet was in danger of sinking, having taken on a great deal of water. The next morning the Duke William was pounded by the sea and sprung a leak, causing it to take on much water.

The Acadians worked frantically to plug the leak and rid the Duke William of water, but to no avail. A squall appeared and when it cleared, the Violet was seen no more - it had sunk with all 400 Acadians on board. Two days later the Duke William was on the verge of sinking. The Captain threw overboard two lifeboats for himself and the crew. In addition, Father Girard, the Acadian priest, climbed into one of the lifeboats - a total of 37 souls in the two lifeboats. Four Acadians found a small jolly-boat, threw it overboard and climbed into it. Moments afterward, the Duke William disappeared under the Atlantic waters bringing over 350 Acadians to their watery graves. Miraculously, all forty-one of the men in the two lifeboats and jolly-boat survived and reached England. The other five ships reached St. Malo on 23 January 1759 with their combined "cargo" of almost 1000 Acadians from Île Saint-Jean many of whom were very ill and had to be hospitalized.

On 25 November 1758 two other ships sailed from Louisbourg harbor for St. Malo. One carrying over 160 Acadians made initial landfall at Bideford, England on 20 December 1758 and then went to St. Malo - arriving on 9 March 1759. Twenty-five of the Acadians died at sea. The other ship with almost 60 Acadians reached St. Malo on 16 January 1759 after 6 Acadians perished at sea.

Five other ships left from Louisbourg in late 1758 for France - four for Cherbourg and one for Boulogne-sur Mer. The four heading to Cherbourg had well over 300 Acadians packed in their holes while the one going to Boulogne-sur-Mer was transporting almost 180 Acadians from Île Saint-Jean. This ship first reached Portsmouth, England about 23 December in great distress, but did continue to Boulogne-sur-Mer, which it reached on 26 December. Three of the ships destined for Cherbourg with Acadians from Île Saint-Jean and Île Royale disembarked its passengers at Cherbourg on 30 November 1758. The fourth Cherbourg-bound ship Ruby with over 300 Acadians from Île Saint-Jean encountered gale-force winds and sank off the Island of Pico in the Portuguese Azores. Over 200 Acadian lives were lost. The survivors were taken first to England - finally reaching Cherbourg on 15 February 1759.

Between 4 September 1758 and 25 November 1758 the British deported over 3600 Acadians to France from Île Saint-Jean and Île Royale. Many of these perished on the voyage through the treacherous Atlantic waters. Three ships sank en route to France - taking with them over 950 Acadian souls to their watery graves. The surviving Acadians, stripped of their worldly goods by the British, languished in the port cities of western France for almost thirty years - many trying desperately to re-establish their lives in various agricultural experiments from the interior lands of France as far as the Falkland Islands and even to French Guyana. In all cases the "deck was stacked against them" with arid conditions, poor soils and tropical heat and diseases and thus never did they achieve success. Thus ends the Islands Campaign to extinguish the Acadian nation.

Rounding Up the Stragglers - A Smaller Exile Lasting Several Years

Having deported over 10,000 Acadians from Nova Scotia, Île Saint-Jean and Île Royale, the British now began in earnest to capture and deport or imprison all remaining Acadians in Nova Scotia, Île Saint-Jean, Île Royale and New Brunswick. They were ferocious in their efforts to track down and capture all Acadians remaining. Villages were burnt and livestock destroyed to prevent the Acadians from having shelter in the harsh winters. Acadians occasionally were killed by the British soldiers at their homes or as they fled.In November 1759 British soldiers captured 151 Acadians at Cap-Sable and sent them to England. Shortly after arriving in England in late December 1759, these Acadians were sent to Cherbourg, France where they arrived in mid-January 1760. It seems the British occasionally forgot international law and exiled Acadians to wrong shores - as here sending British citizens to France.

In November 1759 after a very severe winter in New Brunswick, over 900 Acadians who initially had escaped the deportations by hiding in New Brunswick began to surrender to British authorities at Fort Cumberland. They were imprisoned at Fort Cumberland, Fort Edward and Georges Island. In July 1760 at the conclusion of The Battle of Ristigouche on the New Brunswick-Québec border, 300 Acadian refugees were captured near Ristigouche and brought to Georges Island and Fort Cumberland.

In August 1762 over 600 Acadians detained at Georges Island, Fort Edward and Annapolis-Royal were loaded onto five ships and sent to Boston. The Governor of Massachusetts refused to accept them and sent them back to Halifax where they arrived in mid-October 1762. They were again imprisoned until the end of the French and Indian War.

On 10 February1763 France and Britain signed the Treaty of Paris ending the Seven Years' War and the deportations. Acadians were now free to move wherever they wanted; however, being penniless, they often remained "imprisoned by their poverty" - petitioning and begging the local governments to send them to Louisiana, Québec, France or Nova Scotia. Alternatively, many accepted free transportation to Saint-Domingue (today Haiti) where most died from the heat, poor living conditions, unbearably hard work and tropical diseases. The hundreds of Acadians in British prisons at Fort Cumberland, Fort Edward and Georges Island scattered to Louisiana, Miquelon, Québec, France and specific regions of Nova Scotia. The British and French governments negotiated an agreement to transfer to France the Acadians imprisoned in England. A few Acadians remained in the colonies to which they were deported.

Thus ended the tragic deportations suffered by the Acadian people. Never again would many Acadians see their wives and husbands, their children, their aunts and uncles, their cousins. Families remained separated for the rest of their lives despite the untiring efforts of the Acadians to reunite their immediate and extended families. Hundreds of Acadians died during the immediate deportations and many hundreds more died during their "imprisonment" in foreign lands. The Acadians, however, remained a strong people, determined to never lose their culture and their identity. This they accomplished in their new homes in Louisiana, Nova Scotia, Maine and Québec.