Bazile Lanneau (1746-1833) of Charleston, SC - Acadian Resistance, Persistence and Triumph

Born in Belleisle, Acadia in 1746 to René Lanoue and Marguerite Richard, Bazile Lanoue was the sixth of seven children. Founded about 1680, Belleisle was one of the earliest Acadian villages on the Annapolis River (originally Rivière du Dauphin) and by the mid1700s became one of the most prosperous. By the early 1700s the Catholic church on the north shore of the Annapolis River, the parish of Saint-Laurent, was at Belleisle.

Bazile Lanoue's great-grandfather Pierre La Noue was born in 1647 in Bogard, France. Pierre, a wealthy Huguenot, lived in France during a period of political and religious struggles between Catholics and Huguenots. To keep his wealth, lands and likely his life, Pierre was forced to renounce his Huguenot religion. In 1667 Pierre left France and sailed to Acadia where religious persecution was not a problem. In Acadia Huguenots and Catholics could intermarry and newcomers could settle any available lands and pursue any occupation. Pierre La Noue settled in the Port-Royal area where he is listed in the 1671 Census as a cooper (barrel maker) and, when asked his age, responded that he felt fine, but would not give an answer.

Apparently, he was still wary of the government after his experiences in France. Pierre La Noue was the last person of the PortRoyal area censused in 1671 and thus likely lived some distance from Port-Royal itself. Pierre almost certainly lived in Belleisle, just upriver from Port-Royal, where he later became the village blacksmith.

About 1682 Pierre married 16-year-old Jeanne Gautrot, daughter of François Gautrot and Edmée Lejeune, at Port-Royal. Pierre Lanoue II, only known son of Pierre La Noue and Jeanne Gautrot, was born 21 November 1682 and married Marie Granger, daughter of Laurent Granger and Marie Landry, on 21 November 1702. They had six sons and two daughters.

The fourth son of Pierre Lanoue II and Marie Granger, René Lanoue was born 2 December 1710. He married at Grand-Pré, Acadia on 8 January 1732 to Marguerite Richard, daughter of Michel Richard and Agnès Bourgeois and the granddaughter of surgeon Jacques Bourgeois. By this time the Lanoue family were well-established Catholics with all their births and marriages registered in the Catholic church.

René Lanoue and Marguerite Richard remained in the Bellisle area and between 1734 and 1750 had seven sons - Joseph (b. 1734), Amand (b. 1737), Jean Baptiste (b. 1738), Gregoire (b. 1741), Pierre IV (b. 1744), Bazile (born 13 November 1746) and François (b. 1750). From the earliest days of the founding of the Acadian colony, there was constant conflict between the British and French over Acadia. There were numerous battles - both localized conflicts and broader battles in Acadia- between the French of Québec and France and the British of Massachusetts and England. Many of these conflicts occurred at Port Royal. The Acadians, knowing that the victor changed frequently, tried to remain neutral and not participate in the conflicts.

Their goal was to live peacefully farming their marshlands and fishing the abundant Acadian waters. During the siege of Port Royal in October 1710 the British captured the fort and never lost control of Acadia after that.

In 1751, shortly after the birth of his son François, René Lanoue died at Belleisle. Marguerite Richard now had seven young boys between one and seventeen years old to raise by herself.

In the early 1750s rumblings began in Acadia about a major international conflict between Britain and France with almost certain spillover into the North American colonies. For many years the British had attempted without success to have the Acadians take an unqualified oath of allegiance to the British monarch. The Acadians refused - insisting on a qualified oath allowing them to maintain their Catholic religion and to not have to take up arms against the British, the French or the Mi'kmaq. Several years earlier many Acadians had taken a qualified oath, but later Acadian governors did not recognize it as valid. In reality the British wanted to rid the colony of Acadians for several reasons. The Acadians vastly outnumbered the British in Acadia and the British feared that they may side with the French in the next conflict; the Acadians had recovered vast amounts of marshland using dykes and this land was exceptionally fertile so the Massachusetts government wanted to confiscate these lands and settle Massachusetts farmers on them and Acadia was situated near the mouth of the St. Lawrence River - the only route to the interior of Canada and its lands.

On 28 July 1755 Acadian Governor Charles Lawrence and his council decided to deport all the Acadians from the country and send them to the British colonies of North America. They developed a secret plan to capture the Acadians, hold them until transports arrived and then deport them throughout the British colonies. Their goal was to destroy the Acadians as a people and make "good" British citizens of them in the colonies. In August 1755 the British began putting their plans into action at the four major Acadian settlements - Beaubassin, Grand-Pré. Pisiquid and Annapolis Royal (Port-Royal). In October 1755 with almost 6000 Acadians loaded on transports, the exodus began. Due to the confusion in loading the transports, many families were separated, being delivered to different colonies - never to see each other again.

Marguerite Richard and her family were able to avoid being deported for a short period, but by December 1755, they were captured and taken to Goat Island in the Annapolis River - opposite the old Port-Royal Habitation. It is uncertain where the two oldest boys Joseph and Amand were sent; however, they did return later from exile to Nova Scotia. Marguerite and her five younger sons were forced aboard the transport Hopson along with 336 other Acadians with only their clothes and a few valuables in their arms, placed into the "hole" below deck with inadequate space, almost no ventilation, little light, poor food and limited water. Master Edward Whitewood then departed Goat Island on 8 December 1755, entered the Bay of Fundy and sailed into the Atlantic Ocean during a freezing, stormy winter. Their provisions were one pound of beef, 2 pounds of bread and five pounds of flour per person per week.

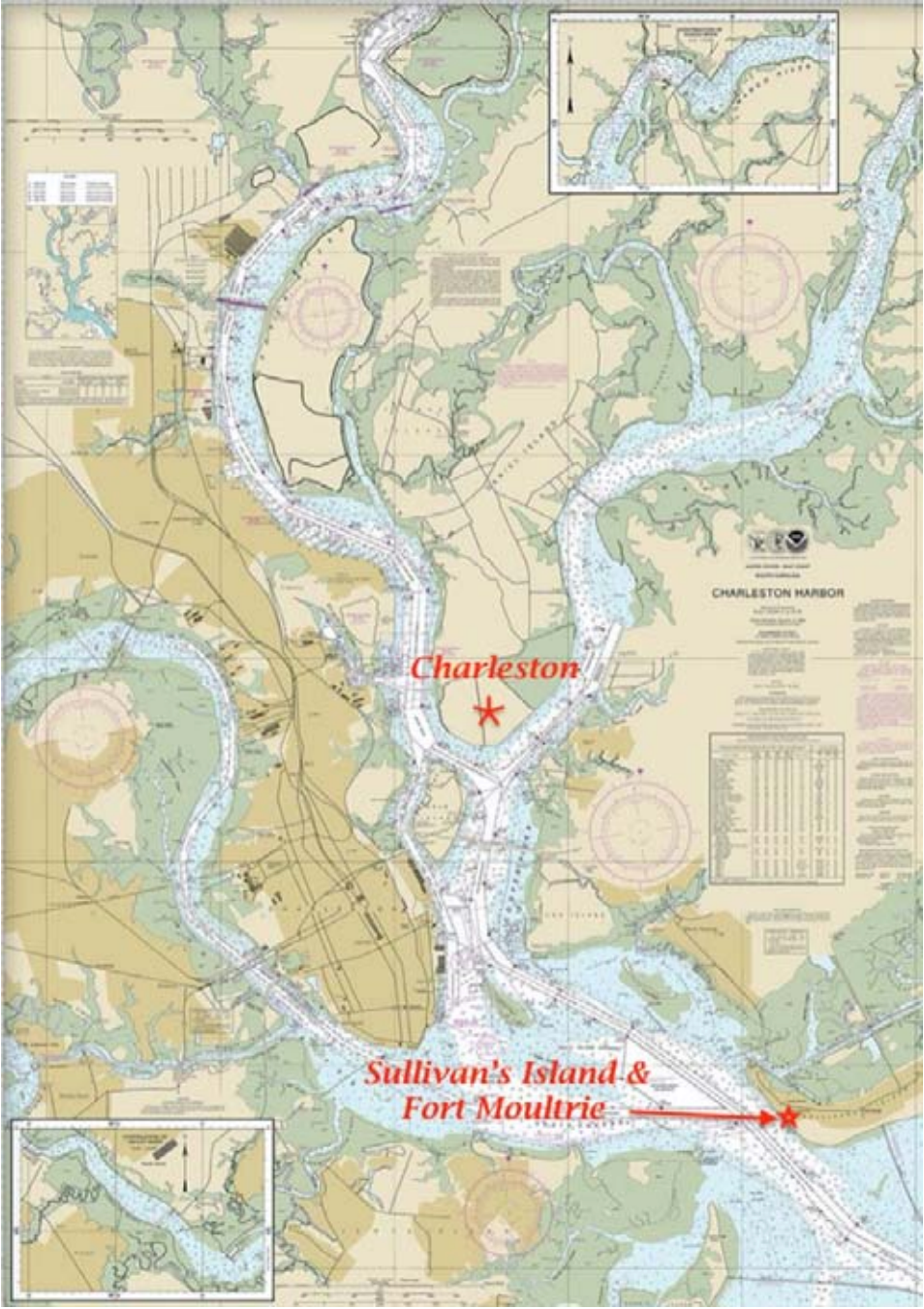

On 15 January 1756 after a voyage of 39 days, the Hopson arrived at Sullivan's Island near Charleston, South Carolina. According to Governor Glen of South Carolina, these Acadians arrived in great distress. The South Carolina House initially refused to allow them to land because the 651 Acadians having already arrived at this port were a significant burden on the town. Governor Glen fought for the Hopson Acadians as they had little rations left and were desperate. Finally, on 5 February 1756 the Acadians landed on Sullivan's Island and were kept in quarantine in the pest house on Sullivan's Island. It likely was located in the parking area of today's Stella Maris Roman Catholic Church just north of Fort Moultrie. The pest house had four to six rooms and was about 16 feet by 30 feet in size. On 22 March 1756 the Acadians were still being quarantined on Sullivan's Island where there was sickness among the Acadians due to the bad water and lack of proper care. Many had died and others were ill. The few valuables, even clothes, that they had carried aboard the Hopson were stolen by the sailors during the voyage so these Acadians had nothing.

Eventually, the Hopson Acadians were allowed to leave quarantine at Sullivan's Island and enter Charleston.

[Note: Although no manifest exists for the Hopson , it appears very improbable that Marguerite Richard and her family could have arrived on any ship except the Hopson . For three of the five transports landing at South Carolina, manifests do exist and Marguerite Richard and her family are not listed on these manifests. These three transports were the sloop Dolphin , the ship Edward Cornwallis and the ship Endeavor . No manifest is known for the brig Two Brothers ; however, it departed from the Beaubassin area with Acadians from Chignectou. Marguerite Richard lived at Belleisle near Annapolis Royal. The Hopson was the only ship arriving at South Carolina that carried Acadians from the Annapolis Royal area. It departed from Goat Island. Although not a transport, the escort sloop Syren carried only 21 passengers who were dangerous and disaffected male prisoners]

From the moment the Acadians arrived in Charleston, they aroused great concern and dissent. Technically, they were British citizens, yet they were Catholic and had French ancestry. South Carolina allowed freedom of conscience, but forbade citizenship to Catholics. Had not Governor Glen fought vigorously for the Hopson Acadians, they likely would have been allowed to perish on the ship in the harbor. Once they were allowed into Charleston, the question of how to support them arose. Citizens in the various South Carolina parishes adamantly refused to assume the burden. In July 1756 the South Carolina government did partition the Acadians to the various parishes despite the resistance.

The Acadians lived for several years in poverty doing what little work was available at low wages and begging. In 1760 a smallpox epidemic hit Charleston and over one third of the Acadians in town perished - leaving countless orphans that were indentured to tradesmen and artisans.

Shortly after arriving in Charleston, Marguerite Richard and her youngest son François contracted "stranger's fever" which likely was smallpox. It is uncertain if her other sons (Jean-Baptiste, Gregoire, Pierre and Bazile) also became ill. Very likely the family was still on Sullivan's Island when Marguerite and François became ill. Mr. Vanderhorst took the family to his plantation where Marguerite and François soon died - leaving JeanBaptiste (age 17), Gregoire (age 14), Pierre (age 12) and Bazile (age 9) as orphans.

Although some sources state that the Vanderhorst plantation was near Charleston where the Battery is today, that appears to be incorrect. The Battery is located on Kiawah Island - about 35 miles southeast of Sullivan's Island. There is a Vanderhorst Plantation located on Kiawah Island; however, it was not owned by a Vanderhorst until 1772 when Elizabeth Vanderhorst, wife of Arnoldus Vanderhorst II, inherited it.

Almost certainly Mr. Vanderhorst, who cared for Marguerite Richard and her sons, lived in Christ Church Parish just north of today's Mt. Pleasant - about 10 miles northwest of Sullivan's Island. By the mid-1700s the Vanderhorst family owned at least four adjacent plantations in Christ Church Parish (located in today's Charleston County). By 1754 Arnoldus Vanderhorst had acquired all the land between Toomer Creek and Wagner Creek in Christ Church Parish including Richmond Plantation, Lexington Plantation, Point Plantation and Vanderhorst Plantation - the original home of John Vanderhorst who immigrated to the area in 1686 and died there in 1717. Arnoldus was a grandson of John Vanderhorst. He is likely the Mr. Vanderhorst that cared for Marguerite Richard and the Lanoue children. It is uncertain to which plantation they were taken.

After their mother's death, Mr. Vanderhorst cared for the four boys. At some point Pierre Lanoue was apprenticed to a physician; howevcr, later the two brothers Pierre and Gregoire Lanoue left Charleston to return to their native Nova Scotia. Jean-Baptiste and Bazile opted to remain in South Carolina and would give their brothers "no ear" to talk of leaving. Living among British citizens, their names became anglicized to John Lanneau and Bazile (sometimes Basil) Lanneau.

John Lanneau remained at the Vanderhorst plantation for a time under the care of Mr. Vanderhorst. Here he became an Episcopalian. Little is known about John's life except that he remained in Charleston during his adulthood and died there at age 42 on 24 August 1781 - possibly of smallpox. On 25 August 1781 John Lanneau was laid to rest in the graveyard of St. Philip's Episcopal Church in Charleston. He had no children during his life. John apparently learned the tanner's trade from his brother Bazile and did acquire some wealth in his lifetime as Bazile Lanneau served as executor of his estate.

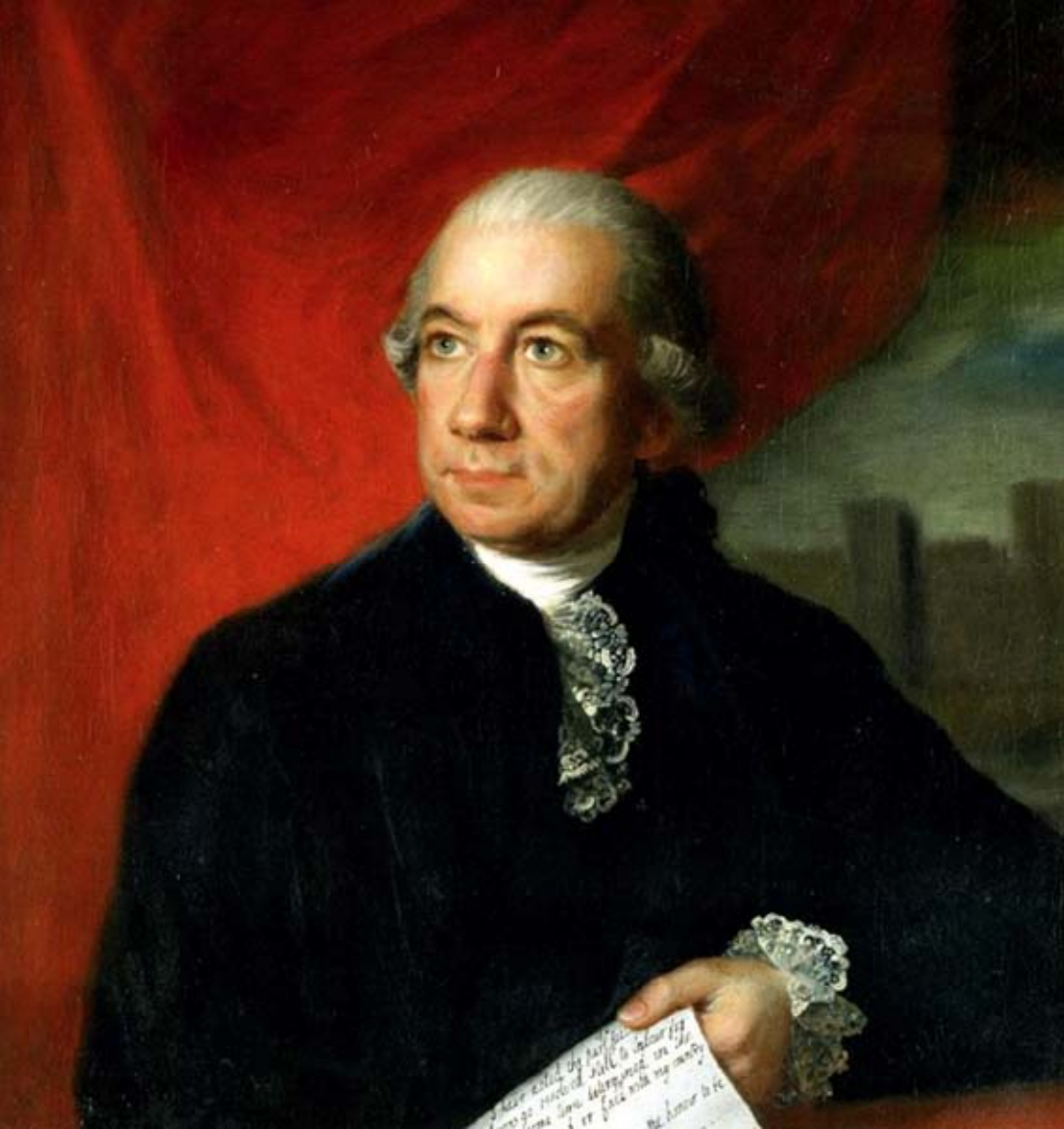

Bazile Lanneau likely lived with Mr. Vanderhorst immediately after his mother's death, but soon caught the eye of Colonel Henry Laurens - a wealthy Charleston merchant with extensive landholdings who traded with England, Spain and the West Indies. After a very successful career as an export merchant in Charleston, Colonel Laurens purchased four plantations in South Carolina where he raised rice and indigo, two plantations in Georgia and town lots in Charleston. In later years he was a member of the Provincial South Carolina House of Assembly, President of the First Provincial Congress in 1775 and Vice-President of South Carolina in 1776. At the national level Colonel Laurens served as a Representative of South Carolina in the Second Continental Congress in Philadelphia and was its President in 1777. In 1780 he was the United States Minister to the Netherlands when he was captured by the British off Newfoundland and imprisoned for 15 months in the Tower of London. He signed the preliminary peace treaty with England after the American Revolution.

Colonel Laurens saw great promise in the young Lanneau boy and took him under his tutelage. Initially, Bazile likely lived with Mr. Laurens and his family in Charleston. In 1762 Laurens purchased Mepkin Plantation in St. James Goose Creek Parish near today's Monck's Corner. He made Mepkin his home and remained there until his death in 1792. Bazile almost certainly moved into Mepkin with Colonel Laurens and his family and remained there for at least a short time.

During his early years Bazile Lanneau worked diligently to educate himself and worked hard at various jobs to provide for his needs. Colonel Laurens taught him how to make shoes and boots and the tannery trade. Industrious and dedicated to his work, Bazile often said that for thirty years the sun never found him in bed. Bazile became a Huguenot, the religion of his great-grandfather, almost certainly through the influence of Henry Laurens, who was a leader in the French Huguenot Church in Charleston.

Bazile's first job as a young man was carrying bricks and mortar for workmen constructing a large building at the corner of Broad and Meeting Streets in Charleston - opposite St. Michael's Episcopal Church. Very likely the building was either the Armory and Guard House (where the present U. S. Post Office and Federal Court are) or the old South Carolina State House that burned in 1788 (where the Charleston County Court House now stands). Soon Bazile established a shoe and boot business on Elliott Street where he likely lived. To expand his business, he began tanning his own leather.

In 1778 Bazile Lanneau purchased from Isaac Harleston six lots in an undeveloped area on the outskirts of Charleston known as Harleston Green. The lots were on the west side of Pitt Street between Beaufain Street and Wentworth Street. On the northwest corner of Pitt Street and Beaufain Street Bazile built his new tannery and shoe factory. Today this location is 1 Pitt Street. Later he built his home next to the tannery at today's 3 Pitt Street. The tannery and shoe factory were large businesses as Bazile owned fourteen slaves in 1790 with most of them working in the two businesses.

These were the years of the Revolutionary War and South Carolina saw considerable military action. Bazile joined the South Carolina militia fighting against the British, provided supplies to the colonial troops and rendered valuable service as an interpreter between the Americans and their French allies. He was exceptionally proud of his service to South Carolina and even in his later years would become quite animated when recalling his military service. One story he related often was a large cannonball flying through the center of the chimney of his home in 1779, rolling across the floor and exiting through the opposite wall leaving a substantial crack.

After Charleston surrendered in May 1780 Bazile along with his fellow militiamen signed the required Oath of Loyalty so he could be paroled and continue his work at the tannery and shoe factory. During the years between May 1780 and December 1782, when the British finally left Charleston, it was a very trying time for Bazile and the other citizens of Charleston. His home was occupied by British and Hessian officers and they often insulted him - a point he never forgot.

About 1766 Bazile Lanneau married Suzanne Frizelle, a young Huguenot lady who had arrived in Charleston from England in 1764. Little is known about Suzanne except that she was beautiful, a good lady and the sister of Stephen Thomas's first wife. Bazile and Suzanne had five children; however, all five died of yellow fever before 1790 and Suzanne died a short time later of the fever. In the 1790 U. S. Census Bazile Lanneau is listed with one adult white female, no children and fourteen slaves. Suzanne and her five children were buried at the French Huguenot Church Cemetery (132 Church Street). The locations of the graves are no longer known. During their marriage Bazile and Suzanne belonged to the French Huguenot Church which was also the church of Colonel Henry Laurens.

Bazille and Suzanne had a home at 34 St. Philip Street. During the construction of a city parking garage on this property in 1974, the home was moved to 2 Pitt Street - directly across the street from the tannery and shoe factory location - and was fully restored. The kitchen building for this home was moved to 76 Beaufain Street in 1975 and was restored.

A widower who lost not only his wife, but also his five children, Bazile returned to Nova Scotia in 1793 in search of his family and a potential heir to his wealth and business. He located his brother Amand, who had returned to Nova Scotia from exile; however, Amand had a difficult time recognizing his younger brother. He last saw Bazile as a nine-year old boy and now forty years later, Bazile was a grown man six foot tall and 200 pounds. After Bazile showed Amand the scar on his arm from a dog bite, Amand knew this was his brother for Amand was the one who had rescued Bazile from the vicious dog over four decades earlier.

While in Nova Scotia, Bazile also learned that his brother Pierre IV had died leaving a widow, two daughters and a son. Bazile convinced his sister -in-law to let him adopt the two younger children Pierre V (age ca.7 years old) and Sarah (ca. 14 years old) and take them back to Charleston with promises of a better life. Bazile wanted to train Pierre V, whom he called Peter, as a tanner and shoemaker and make him the heir to Bazile's business. Peter, however, did not like this work and eventually was bound out to a navigator leaving Bazile with no heir. Peter became a seaman, married Rebecca Armstrong, had two sons and left progeny in the Charleston area. Sarah married at age sixteen in 1795 to David Bell and began her own family. Later Bazile sent for his brother Pierre's third child Mary who had married Aquilla Enslow and became widowed when Aquilla drowned. They had one son. Mary and her son came to Charleston in 1795 and lived with Bazile for quite some time.

On 27 October 1796 Bazile married a second time to Anne (Hannah) Vinyard, a German girl born in 1768 to John Vinyard and Annie (Hannah) Mortimer. She was 25 years younger than Bazile, but he had known her all his life. Anne's parents and Bazile and Suzanne were close friends and neighbors. Little Anne, whom Bazile called Hannah, was his pet and he enjoyed teasing and playing with her when she was young. He often teased his wife by saying that Hannah would one day be his second wife. Years later, as a widower, Bazile remembered Hannah and married her at the St. James Goose Creek Parish Church. After his marriage Bazile and his wife joined the Circular Congregational Church in Charleston. They lived in Bazile's home at 3 Pitt Street next to the tannery and shoe factory. Here Bazile began his second family. Hannah had nine children with Bazile; however, five of them died young. They were: Margaret Elizabeth (b. 1798), a unnamed daughter that died at birth (b. 1799), Mary Lanno (b. 1800), an unnamed son that died very young (b. 1803), Emma Louisa (b. 1805), Bazile René (b. 1806), Charles Henry (b. 1808), John Francis (b. 1809) and Joseph Sanders (b. 1813). By 1828 only Emma Louisa, Bazile René, Charles Henry and John Francis were living.

It is uncertain how the children were educated, but it seems likely they either were taught at home or by a tutor. John Francis Lanneau later received a college education. The church was close to the hearts of Baziel and Hannah and their faith carried over to their children. Emma Louisa Lanneau married an evangelist and editor of religious papers. Bazile René Lanneau and Charles Henry Lanneau served their churches as Sunday schoolteachers and superintendents. Bazile René Lanneau married a minister's daughter and their son became a minister. Charles Henry Lanneau became a minister in later life. John Francis Lanneau became a minister and devoted his life to missionary work abroad.

On 9 November 1833, just four days shy of 87 years, Bazile Lanneau died in Charleston after a brief illness. His will left his extensive estate to be divided equally among his wife Hannah and his four surviving children. Bazile's life was truly one of astounding successes among heart-breaking tragedies. Exiled from his home at nine years of age with nothing but the clothes on his back, stuffed into the hole of an over-crowded ship for a 39-day voyage, held on the ship for an extended period after reaching Charleston, kept for many days in the pest house on Sullivan Island watching his fellow Acadians die and then losing his mother and brother shortly after arriving in Charleston. He fought on, learned a trade and built a very profitable business through sweat and hard work never looking back. Marrying and then losing his wife and all five of his children to yellow fever certainly was a devastating blow. Yet, he picked himself up, went to Nova Scotia, found a brother and the children of another brother and brought the children to Charleston so he could offer them a better life. He remarried and had nine additional children - five of whom died young. Yet he strove forward leading a life in which he prospered in business, had a reputation of great personal integrity and was a highly regarded member of the community.

Three times Bazile was elected to represent St. Philip's and St. Michael's parishes in the South Carolina General Assembly in 1796, 1798-1799 and 1802-1804 - never having solicited a single vote. Between 1788 and 1826 he was Commissioner of the workhouse and markets for Charleston. Other positions he held included a member of the Fellowship Society, an Elder in the French Huguenot Church in 1788 and 1790, a Trustee of the Mechanic Society, the Commissioner to assess damages sustained by owners of lots and houses near State Street in 1811, a Director of the Bank of South Carolina and the Commissioner of the Charleston Dispensary in 1815. His strong belief in education was demonstrated by his having held a Builder's Share in the Charleston Library Society for his contribution to its first building. In these activities and in his business affairs he associated with many of South Carolina's best known families.

After Bazile's death Hannah sold their home at 3 Pitt Street and lived first with her daughter Emma Louisa and then later with her son Bazile René until her death on 29 April 1847. Bazile and Hannah are buried in Circular Congregational Churchyard at 150 Meeting Street in Charleston. Their side-by-side gravestones have beautiful inscriptions. Bazile's gravestone is one of very few surviving gravestones of Acadians who were deported.

The gravestones read:

Sacred

to the Memory ofBAZILE LANNEAU

Who was born at Balisle N.S., 1744

In 1755 he became a prisoner of war

And was transported to this city

Where he was left

A Stranger and an Orphan.

Where he filled with honor and integrity

Many important and responsible stations

And sustained the relation

Of Husband, Father and Friend

With distinguished fidelity

Sincere affection and rare benevolence

And where he died, Nov. 9, 1833

Leaving an afflicted Widow and four children

To hold his name and many virtues

In Affectionate Remembrance.

Sacred

to the Memory ofHANNAH LANNEAU

Consort of Bazile Lanneau

Who departed this life 29th April 1847

In the Seventy Ninth Year of her Age

In health and sickness, in life

And in death, she was sustained

By the consolations of the religion

Of Jesus which she long professed;

And which she fully exemplified

In her daily walk and conversation

For her "to live was Christ" - to die gain

This stone is erected to her Memory

By her Four Children

Who hope they have obtained

"Like precious faith"

And who still live to cherish her

Meek Christian example

And maternal virtues

In sacred and affectionate

Remembrance.

The error in Bazile Lanneau's birth year on his gravestone (1744 rather than 1746) certainly is understandable as he was quite young when exiled and may not have remembered the year of his birth after such a trying experience in his youth.

After the death of Bazile, his children built homes on the Pitt Street lots that they inherited from their father. Charles Henry Lanneau built his home at 1 Pitt Street where the tannery and shoe factory once stood; Emma Louisa Lanneau Gildersleeve built a home at 5 Pitt Street and Bazile René Lanneau built at 7 Pitt Street. The houses at 9 Pitt Street and 11 Pitt Street also have been attributed to the Lanneau family although the house at 11 Pitt Street has been torn down. These homes as well as the home at 2 Pitt Street which was moved from 34 St. Philip Street and the kitchen house at 76 Beaufain Street which also was originally at 34 St. Philip Street stand today as a testament to the will and determination of Bazile Lanneau.

Bazile's four surviving children and his three "adopted" children of his brother Pierre had very successful careers and left many descendants that today are found throughout the southeastern United States including South Carolina, North Carolina, Mississippi, Louisiana, Virginia, Tennessee, Kentucky, Texas and other states. Bazile Lanneau built a strong family foundation during his life and his legacy lives on today through his descendants.

References

Books

- Gaudet, Placide; Report Concerning Canadian Archives for the Year 1905 in Three Volumes, Sessional Paper No. 18 (S.E. Dawson; Ottawa, Canada; 1906; Volume II, Appendix A; Pages 15-21)

- Milling, Chapman J.; Exile Without An End (Bostick & Thornley, Inc.; Columbia, SC; 1943)

- Mowbray, Susie R. & Norwood, Charles S.; Bazile Lanneau of Charleston, 1746-1833 (Hilburn Printing Corporation; Goldsboro, NC; 1985)

- Smith, D. E. Huger & Salley, A. S., Jr.; Register of St. Philip's Parish, Charles Town or Charleston, S. C., 1754-1810 (The South Carolina Society of the Colonial Dames of America; Charleston, SC; 1927; Page 347)

Journal Articles

- Jones, David Clyde: "Exploring the Huguenot Legacy in South Carolina: How an Exiled French Acadian Family Made Baptist and Presbyterian History ( Presbyterion: Covenant Seminary Review ; Covenant Theological Seminary; St. Louis, MO; Volume 40; Fall 2014; Pages 14-26)

- Stoesen, Alexander R.; "The British Occupation of Charleston, 1780-1782" ( The South Carolina Historical Magazine ; The South Carolina Historical Society; Charleston, SC; Volume 63 No. 2; April 1962; Pages 71-82)

- Webber, Mabel L.; "Marriage and Death Notices from the Gazette" ( South Carolina Genealogical and Historical Magazine ; South Carolina Genealogical and Historical Society; Charleston, SC; Volume 23; 1922; Page 205)

- Youell, Lillian Belk; "Henry Laurens, the Neglected Negotiator" ( Daughters of the American Revolution Magazine ; Daughters of the American Revolution; Washington, D.C.; Volume 117; No. 7; August - September 1983; Pages 708-712)

Unpublished and Personal Accounts

- Enslow, Joseph La Noue (grandson of Pierre LaNoue IV); Letter written in 1865 giving a brief history of the family's exile to Charleston and Pierre's return to Nova Scotia. Found in application of Oscar Rogers Wilhelm, Jr. for membership in the Huguenot Society of South Carolina, 1942.

- Lanneau, Alfred; "Bazile Lanneau, the Exile" (Unpublished Manuscript)

- Lanneau, Bazile René; "Schematic Chart of the Lanneau Family in France, Acadia and South Carolina"; (Unpublished Manuscript)

- Lanneau, Charles Henry; "Recollections of My Father, Bazile Lanneau, Taken from Conversations Had with Him" (Handwritten Unpublished Account, 1869)

- Pratt, Joannah Gildersleeve; "Memoirs" (Unpublished Memoirs on file at Presbyterian Historic Foundation; Montreat, NC)

Newspapers

- Royal Gazette of South Carolina (R. Wells & Son; Charleston, SC) Issue of September 1-5, 1781, Page 3

- Charleston Courier (A. S. Willington for Loring Andrews; Charleston, SC) Issue of November 9, 1833

- The Post & Courier (Charleston, SC; "Do You Know Your Charleston: Society May Move Doomed Buildings"; ca. 1975)

Original Documents

- Charleston Deed Book Z-4 , Page 469; Charleston County Court House; Charleston, SC

- Charleston County Will Book 39 , Pages 1216-1218; Charleston County Court House; Charleston, SC