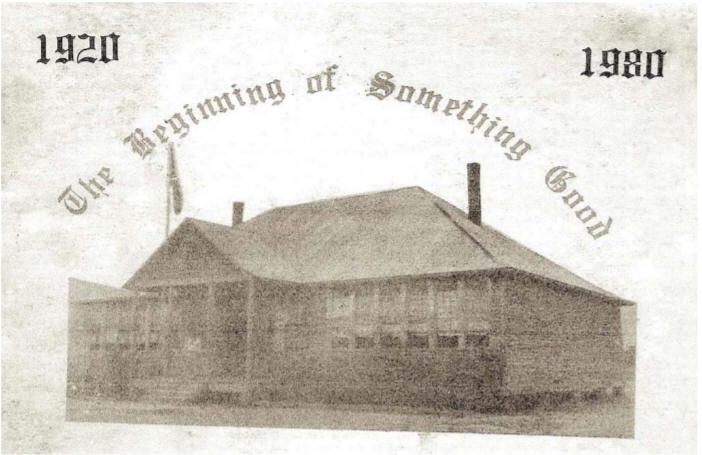

Historic Plaisance Rosenwald

I remember well the first grade classroom where I first started school even though I had no idea it was a Rosenwald. Children set in rows just as many did as they learned their nursery rhymes, counting, beginning writing skills, simple word recognition, learning to get along with the person next to you, wondering why the teacher had placed the student in front whose head reached higher than yours, preventing you from seeing what was going on in front. The children would line up before noon, as the teacher turned on the water spigot so they could wash their hands, water flowing one drop at a time from the small barrel as it dripped into their tiny hands. The teacher prepared the wood barrel daily, placing water inside to swell the planks of wood, keeping them tightly joined to each other, preventing the precious water from escaping before the barrel ran dry. I do not know where the water came from, perhaps from a local well on the school property but the children knowing the resource was limited, had to share while it lasted.

The tall narrow windows opened to the southern sky, taking in soft patterns of light, punctuated by long columns separating narrow and graceful windows, kept the children warm throughout the year. When opened they let in cool gentle winds from the southern skies in the hot season and when closed sealed out the sometimes harsh arctic air of cold winters. The architects of Tuskegee Institute perhaps among the finest of the south with Booker T. Washington and Julius Rosenwald as their visionaries and guides, knew how to design buildings to make best use of the environment without even a mechanical ventilator. Windows opened and closed according to the weather. Even interior walls could slide open to accommodate larger groups for special attractions.

Winters could sometimes be harsh in the south. One coal burner per classroom kept everyone warm. The children, now older in grade 4, took turns stoking the fire, using a long metal rod to turn over coals heating the entire room. In the late afternoon, the children rolled compound over oiled floors, product of local trees. No painted wood was seen anywhere, just oiled floors on the inside and natural timber on the outside.

During recess, children paced the school campus, sometimes speaking in English, at other times in their home language, Cajun French. During the school fundraising period, they sold sweet potato pies, neatly arranged on small trays with waxed paper coverings. On the outside, the pies folded over like modern day apple pastry. On the inside, they were colored a lovely golden flesh, gave off sweet aromas, nearly baked over by the steamy Louisiana sun. They were sumptuous, delights you never wanted to end. Though some children came from small farms that their families owned, Plaisance was in the middle of a sharecroppers’ area so one knew the children had a life with the sweet potato that stretched beyond selling pies.

In the fall, potato diggers were excused from class to harvest the family crop. No matter where one traveled along Highway 167 slicing through Plaisance, one saw sweet potato vines stretching atop elevated rows that seemed to go on forever. During harvest time, the children pushed their small hands deeply into the soil, bringing up the year’s yield, one sweet potato at a time, dusting them off bit by bit, casting them into wooden crates and even dumping them directly into mule drawn wagons.

Nearly all products going into baking sweet potato pies - butter, cane syrup, sweet potatoes themselves, originated in small local fields. Farmers harvested tall, graceful stalks of sugar cane, cut into short bamboo like rods, heated in large vats until pulp juiced into a molasses like consistency, filling the room with a new delicate sweetness. Sometimes, a local community mill turned the stalks into syrup but most frequently families did the work themselves overseeing the entire process from field planting to harvesting and final product, resulting in transforming sugar cane into thick and tasty syrup. Pies then reached the school grounds or were sold at a local market. All of this was to support their families and their school.

In the 1960’s, when schools were ordered to desegregate, battle lines were formed against having children of Plaisance sent to a local school meaning that the Plaisance School would shut down. The community fought against it, rising up meeting after meeting to make their voices heard. They did not mind having children from other areas attend Plaisance School as had been done on other occasions but were against having their own local school closed. Finally, after much debate in the community, they were advised that the school would not shut down and that they could continue to send their children to their local school.

Today, Plaisance School is the only Rosenwald building in Louisiana operating continuously since 1920. It is now a middle school and the band practices consistently in the original all wood structure built in 1920. The National Trust for Historic Preservation awarded the school an historic marker, a living testament to a community’s determination to succeed.

Art Guidry is a digital media entrepreneur who produces, directs and writes content. He started first grade at Plaisance School and now makes his home in New York City. His father, Matthew Millard Guidry of Opelousas, was principal of Plaisance School from 1944 to 1962. Among his dreams was to grow the school from an elementary one to a complete education center serving the Plaisance area from First Grade through High School, which he achieved during his life. He passed away while in office in 1962.