Pierre Guédry dit Labine and the Battle of Grand-Pré - 10-12 February 1757

A rather unknown battle that was a stepping-stone to the Acadian deportations, the Battle of Grand-Pré was known also as the Battle of Minas, the Attack at Grand-Pré and the Grand-Pré Massacre. It was one of the most gallant exploits in French-Canadian military history.

In 1744 and in 1745 French forces had used Grand-Pré as a staging ground for sieges on Annapolis Royal. In 1746 another failed siege attempt on Annapolis Royal occurred. The frustrated British wanted to take control of Grand-Pré and end these irritations.

Anticipating a major engagement with the British, in June 1746 the French at Québec sent Captain Ramezay with 600 Canadian military to the Chignecto area near Beaubassin (today Amherst) to join 300 Malicites and a large body of Mi'kmaq. They were staged to assist the French navy in attacks on Louisbourg and Annapolis Royal. Due to various complications, the French navy did not arrive in time for the planned summer attacks in 1746. Ramezay did march his forces to Annapolis Royal in October and camped about two miles from the fort, but the navy never appeared so he and his forces returned to Chignecto in early November. The prepared to winter at Chignecto and made camp.

The presence of the French navy in Nova Scotian waters enhanced the fear of New Englanders. Massachusetts Governor Shirley immediately sent 300 Massachusetts militia to reinforce Annapolis Royal. Governor Shirley then sent another 500 Massachusetts militiamen under Colonel Noble to interior Nova Scotia. They arrived at Annapolis Royal in late Fall 1746, and immediately departed for Grand-Pré to construct an English fort including two blockhouses in preparation for a spring offensive against the French at Chignecto. In early January 1747 the British forces arrived at Grand-Pré with the ground covered in snow and the soil frozen. They anchored their two vessels containing food, ammunition and building supplies midstream in the nearby Gaspereau River and established winter camp at Grand-Pré. With winter in full swing the British decided to wait until the snows subsided before constructing the blockhouses and unloading the two ships. After all, the French, Malicite and Mi'kmaq at Chignecto were 150 miles away - separated from Grand-Pré by frozen rivers and snow-laden, pathless forests. Initially, the 500 British troops were billeted in Acadian homes at Grand-Pré and in nearby communities; however, Colonel Noble soon ordered that all of the troops be brought to Grand-Pré and distributed into 24 Acadian houses that stretched over two and one-half miles. All, but one, of the structures were wooden. One large building was made of stone.

Captain Ramezay at Chignecto learned that several hundred British troops were wintered at Grand-Pré. He reckoned that this force was larger than his and he would likely be attacked at Chignecto in the spring. He thus determined that his best course of action was to march overland to Grand-Pré and surprise the British in a winter attack - a technique not unknown to the French. Because Ramezay was not feeling well at the time, he appointed Nicholas Antoine Coulon de Villiers to lead the attack. He also had several capable officers assisting Coulon de Villiers.

On 23 January 1747 about 200 hundred snow-shoed Canadian soldiers hauled their sledges across the Isthmus of Chignecto to the headwaters of Baie Verte on the eastern edge of the Chignecto peninsula. As they sludged through the snow toward Grand-Pré, they gained additional people. From the shores of Baie Verte, they followed the shore of the Northumberland Strait to Tatamagouche - a two-day trek. Here they replenished their supplies and turned inland for Cobequid (today Truro). To reach Cobequid, they used the well-traveled road for cattle drives and other business. They followed the frozen French River and then crossed the Cobequid Mountains to reach Nijaganiche on 31 January. Here the Acadians replenished the supplies of the French soldiers who then headed east to Cobequid where they got additional provisions. Just ahead was the almost impassable Shubenacadie River near Old Barns.

Because of the high Bay of Fundy tides in this area, the Shubenacadie River did not freeze near its mouth. The French could not assemble enough canoes for all to cross; therefore, Coulon de Villiers sent Ensign Boishebert and ten men across the hazardous river to the western shore to secure the road to Pisiguit (today Windsor). Coulon de Villiers and the rest of the party then proceeded 25 miles on the eastern shore to where the Stewiacke River joined the Shubenacadie. After crossing the frozen Shubenacadie there, the French trekked to the headwaters of the Kennetcook - reaching it on 7 February and rejoining Boishebert and his ten men. Following the frozen Kennetcook River to Pisiguit, the French were a bit cautious in the event that some British had stationed themselves within the village of Pisiguit. They reached Pisiguit on 8 February and found no British. For the first time on their march the French soldiers were able to sleep within homes with guards posted on the roads. By noon on 9 February the French pushed forward toward Grand-Pré - only a few miles farther. A severe winter blizzard began as they marched making travel extremely difficult, but also securing their element of surprise.

Halfway to Grand-Pré, Coulon de Villiers halted his 300 or so men as he divided them into ten squads to prepare the attack. Through the driving snow they proceeded a short distance and halted again to await darkness and increase the element of surprise. They could see the flicker of lights in Acadian homes along the Gaspereau River. One squad cautiously approached the first house and heard loud music and voices. As they peered through a window, they realized there had been a recent marriage and this was the reception. No British could be found. The advance guard returned to the waiting French soldiers and a detachment was sent to the home. It was the home of the Melancon family on the eastern shore of the Gaspereau River. They told the French that the British were occupying the 24 homes on the western shore of the river. It was late on the evening of 9 February. The French then planned the attack. Each of the squads was assigned two specific houses to attack. The attack was to begin at 2:30 am on 10 February - at which time each squad was to creep up quietly to the first of their assigned homes and strike. The French priest then held a short mass and blessed each of the men.

Shortly before 2:30 am each squad began to get into position unbeknown to the sleeping British. The howling, blowing snow provided cover, but also made it difficult for the French soldiers to determine exactly where they were. To the surprise of startled British militiamen, the attack began in earnest as axes split open doors and shots rang out. Many British were killed outright, others wounded. Prisoners were taken. Some British were able to grab a weapon and fire back - wounding and killing a few French. Many of the surviving British ran from their abodes to the Stone House - which protected them from musket balls and fire. About 300 British survived the hostile fire and crowded inside the Stone House.

As day broke on 11 February, the British attempted a morning counterattack, but quickly realized that the waist-deep snow precluded the attack and quickly retreated to the Stone House. Eventually, the ranking officer from each side met over the course of the day and worked out the beginning of an armistice. There would be a ceasefire until 9:00 am on 12 February. The leaders met again on the 12th and agreed that the British would be allowed to return to Annapolis Royal and could not bear arms for six months. The French, being victorious, would get all the armament, supplies, the two ships and British prisoners. The armistice was signed.

It was a deadly battle. The British lost 67 killed including Colonel Noble and his brother, 40 wounded or sick and about 40 prisoners. The French lost 53 men and Coulon de Villiers was severely wounded. The British marching back to Annapolis Royal through the heavy snow suffered immensely from extreme fatigue, colds and other difficulties during the six-day trek. Over 150 of them died.

Shortly after the Battle of Grand-Pré, the French left the village and retired to the Cobequid region. The New England militiamen returned to Grand-Pré in March 1747.

Pierre Guédry dit Grivois

Pierre Guédry dit Grivois (also called Pierre Guédry dit Labine) and at least eleven other Acadians provided direct support to the French troops. Acadians guided the French from the Beaubassin area during the march to Grand-Pré. The French also met guides at the Melancon home that directed them to the 24 homes at Grand-Pré that housed the British. Pierre Guédry dit Grivois helped guide the French troops. It is uncertain if any Acadians actually took up arms against the British at Grand-Pré.

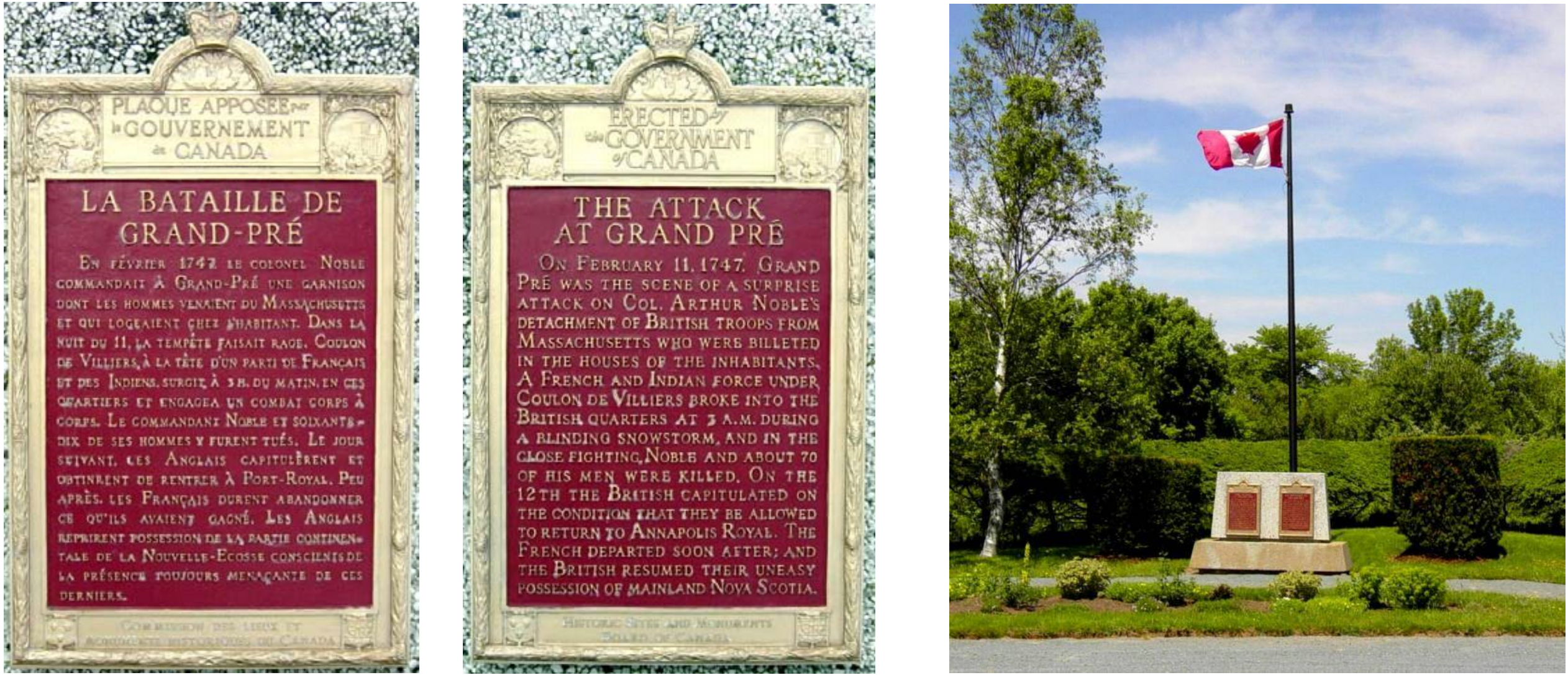

Monument to Battle

A monument to the 1747 Battle of Grand-Pré is located in the village of Grand-Pré, Nova Scotia at the intersection of Grand-Pré Road and Old Post Road - about two blocks from Grand-Pré National Historic Site.

Translation

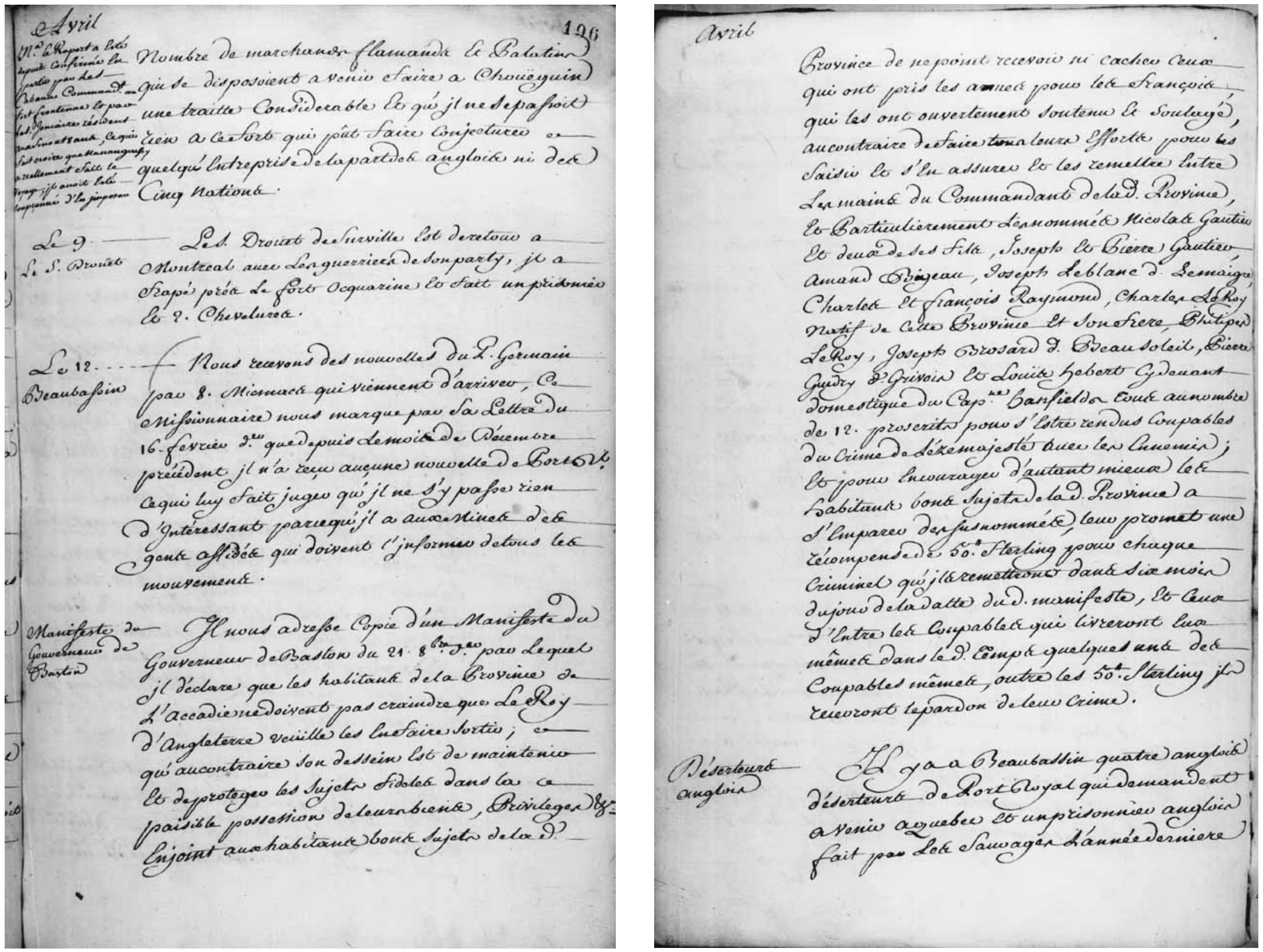

I send you a copy of a Proclamation from the Governor of Boston of October 21 by which I declare that the inhabitants of the Province of Acadia must not fear that the King of England wants to remove them, which would be contrary to his Purpose to maintain And protect the Faithful Subjects in the peaceful possession of their property, Privileges etc. Direct the good subjects of the said Province not to receive or hide those who took up arms for the French, who openly supported them and assisted. On the contrary, to make all their efforts to seize them and secure them and hand them over into the hands of the Commandant of the said Province, And Especially Those named Nicolas Gautier and two of his sons, Joseph and Pierre Gautier, Amand Bigeau, Joseph Leblanc dit Lemaigre, Charles and François Raymond, Charles LeRoy native of this Province and his brother, Philipe LeRoy, Joseph Brosard dit Beausoleil, Pierre Guedry dit Grivois And Louis hebert formerly servant of Captain Barfield, all in number of 12 proscribed for being Guilty of the Crime of High treason to the Enemy. And to encourage all the better the good residents of the said Province to take possession of the aforementioned, he promises them a reward of 50# Sterling for each criminal that they will deliver in six months from the date of the said proclamation, And Those among the Criminals who will confide Themselves according to the said Report some of the same Criminals, besides the 50 # Sterling they will receive forgiveness for their crime.

Transcription

Je nous adresse copie d'un Manifest du Gouverneur de Boston du 21 Octobre par Lequel je déclare que les habitants de la Province de L'Accadie ne doivent pas craindre que Le Roi d'Angleterre veuille les En faire Sortie, ce qu'aucontraire son dessein Est de maintenir Et de proteger les Sujets fideles dans la ce paisible possession de leur biens, Privileges etc. Enjoint aux habitans bons sujets de la dit Province de ne point recevoir ni caches ceux qui ont pris les armes pour les françois qui les ont ouvertement soutenu et soulagé aucontraire de faire tous leurs Efforts pour les Saisir Et s'En assurer Et les remettre Entre Les mains du Commandant de la dit Province, Et Particulierement Les nommés Nicolas Gautier Et deux de ses fils, Joseph Et Pierre Gautier, Amand Bigeau, Joseph Leblanc dit Lemaigre, Charles Et François Raymond, Charles LeRoy natif de cette Province et son frere, Philipe LeRoy, Joseph Brosard dit Beausoleil, Pierre Guedry dit Grivois Et Louis hebert Ci-devant domestique du Captain Barfield tous au nombre de 12 proscrit pour s'Estre rendus Coupables du Crime de Lèsemajesté aux le Ennemi Et pour Encourage d'autant mieux les habitants bons Sujets de la dit Province a s'Emparer de susnommés, leur promet une recompense de 50# Sterling pour chaque criminel qu'ils remettrons dans six mois du jour de la datte du dit manifeste, Et Ceux d'Entre les Coupables qui livreront Eux même dans le dit Compte quelques uns des Coupables mêmes, outre les 50# Sterling ils recevront la pardon de leur crime.

Original Document at:

"Journal of La Galissionière et Hocquart (1747-1748)" - Archives National d'Outre-Mer; Aix-en-Province, France; MG1, C11A, Volume 87, Folios 196-196v