A Unique Gift from the Acadians to Their Andover Landlord

13 October 1755 - A fateful day in Acadian history for on this day the British began deporting the Acadians from their homeland. On October 13 th eight ships packed with 1,100 Acadians left the Chignectou area (Beaubassin) headed for South Carolina and Georgia. 1 Shortly thereafter would follow the deportations of thousands more Acadians from Grand-Pré, Pisiguit, Annapolis Royal and Georges Island. These ships of horror would continue to send multitudes of Acadians to the British colonies of the Atlantic and to France. It would not end until 1763.

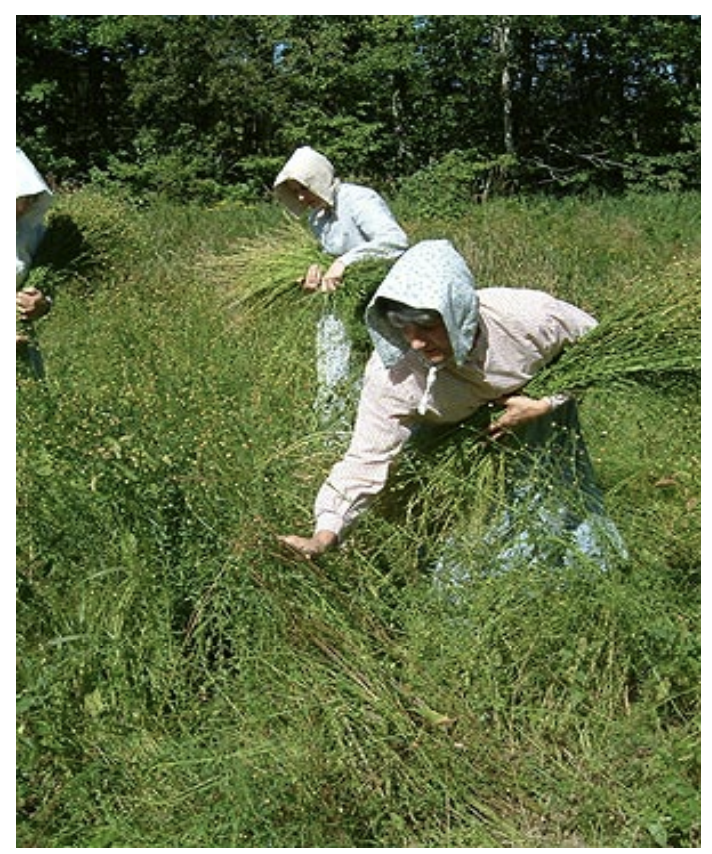

On 19 August 1755 Lt. Col. John Winslow of the Massachusetts militia arrived at Grand-Pré with 300 Massachusetts provincial soldiers. They came from their previous assignment at the Chignecto peninsula. 2 Winslow immediately began fortifying the area around the Saint-Charles-des-Mines Catholic Church to protect his soldiers from the 2100 Acadians in the area who had no concept of what was about to happen. This was to be his base of operations. The soldiers erected a palisade around the church, the priest's home and the cemetery. Winslow moved into the home of the priest and his soldiers pitched tents within the palisade. 3a The Acadians were harvesting their crops - not realizing this would be their last harvest.

On 4 September Winslow issued an order for all Acadian males ages 10 and above to come to the church in Grand-Pré at 3:00 pm the next day for an important announcement. On 5 September 418 Acadian males from the nearby villages walked through the palisade, past the armed soldiers and entered the church. As the last Acadian entered, the soldiers sealed the doors shut and Lt. Col. Winslow read the deportation orders from Governor Charles Lawrence. The British were going to deport them and their families. All of their lands, homes, effects and livestock were forfeited to the Crown. They only could take their savings and some personal items from their homes. No destination was given to them. 3b

Among those in Saint-Charles-des-Mines Church that fateful day were Germain Landry from the Village des Antoine; Jean-Baptiste Landry, a son of Germain, from the Village des Antoine; François Landry, another son of Germain, from the Village des Antoine; Joseph Landry, also a son of Germain, from the Village des Antoine; Jacques Hébert, son-in-law of Germain, from the Village des Hébert dit Groc, Amand Dupuis, another son-in-law of Germain, of the Village des Dupuis and Charles Hébert, also a son-in-law of Germain, from the Grand-Pré area. 3c

The women, girls and young boys stayed in their homes in the various villages of the Grand-Pré region while the men were imprisoned in Saint-Charles-des-Mines Catholic Church under armed guard. Lt. Col. Moncton allowed the Acadian men to select ten of their number from the Grand-Pré area and ten from the Rivière-aux Canards and Rivière des Vieux Habitants to go to the villages and tell the families what was happening. They were also to bring information on any Acadia men absent from the church. 3d

The British strategy relied on the women and families staying at their homes and harvesting the crops while the men remained confined. The women also had to provide food and clothing to the men and boys at the church. A few men at a time were allowed to return to their families to assist with the harvest; however, they must return to the church to avoid endangering the other Acadians. Because of the large number of Acadian men imprisoned compared to the relatively small number of soldiers, Winslow on 7 September 1755 loaded 250 Acadian men on the five available transports while he awaited the arrival of sufficient ships to deport all the Acadians of the Grand-Pré region. 3e

Most of the transport vessels arrived by 7 October 1755; therefore, on 8 October Winslow began embarking the Acadians onto them. His goal was to keep villages together as much as possible and to keep families together. In the confusion of loading this did not always occur. It was a sad day as the men joined their grieving families and reluctantly, they climbed into the rowboats to be brought to the awaiting ships. The very young and the old had to helped or carried into the rowboats and onto the ships. Often personal goods could not be brought on board due to limited space. Families became separated as rowboats filled and some of the family had to await the next rowboat - which often went to a different ship and a different destination. The soldiers were not to load more than 2 people per ton of the ship; however, almost always the ships became overloaded which resulted in very cramped space and not enough food and water for all the Acadians onboard. It also caused greater illness and allowed disease to spread rapidly - resulting in many deaths. 3f As the Acadians were being embarked forcibly on the vessels, they turned and could see their homes, farms and church ablaze - fires purposefully set by British soldiers so the Acadians would not try to return to their villages. On 27 October with favorable winds many of the vessels overfilled with Acadians began departing the Gaspereau anchorage (Horton's Landing) and Boudrot Point (Starr's Point today) for Annapolis, Maryland; Philadelphia, Pennsylvania and Hampton Roads, Virginia. Meanwhile Winslow had to await other vessels to load the remaining Acadians. 4a

As more ships arrived, they were overfilled with Acadians and sailed to their designated port. The Brigantine Swallow , 102 tons under Captain William Hayes, sailed from its Gaspereau anchorage on 13 December 1755 with 236 Acadians packed into its hole and arrived at Boston, Massachusetts on 30 January 1756. A week later on 20 October the Schooner Racehorse with Captain John Banks departed the Gaspereau with 120 Acadians and after a fast voyage of six days reached Boston on 26 December 1755. 4a Among those cramped into these two vessels were Germain Landry, his wife Cécile Forest and their daughters Marie-Josephe, Cécile, Anastasie and Isabelle-Praxède; their son Joseph Landry and his wife Marie; their son Jean-Baptiste Landry; their son François Landry; their son-in-law Jacques Hébert, his wife Marie Landry and their daughters Marie-Josephine, Marguerite, Marie-Josephe, Marie-Magdeleine and Elizabeth; their son-in-law Amand Dupuis, his wife Marie-Blanche Landry and their daughter Marie-Josephe and Charles Hébert and his wife Marguerite-Monique Landry. As noted above, these families had resided in the three small communities Village des Antoine, Village des Hébert dit Groc and Village des Dupuis (near present-day Canard and Port Williams). 4b

Once the Swallow and Racehorse reached the harbor at Boston, the Massachusetts authorities refused to let the Acadians disembark for several days. The Acadians were tired and sick, poorly fed with a bad water supply. The local people despised and feared the Acadians who were French and Roman Catholics. The French and Indian War was heating up and a Catholic was the worst of the worst to these Puritans. The conditions on the ships were dreadful - people were suffering horribly with smallpox and malaria prevalent. Would they be a burden to society once they came ashore? Some in Massachusetts took pity on the Acadians and tried to assist them - including Thomas Hutchinson of the General Court and Reverend Ebenezer Parkman.

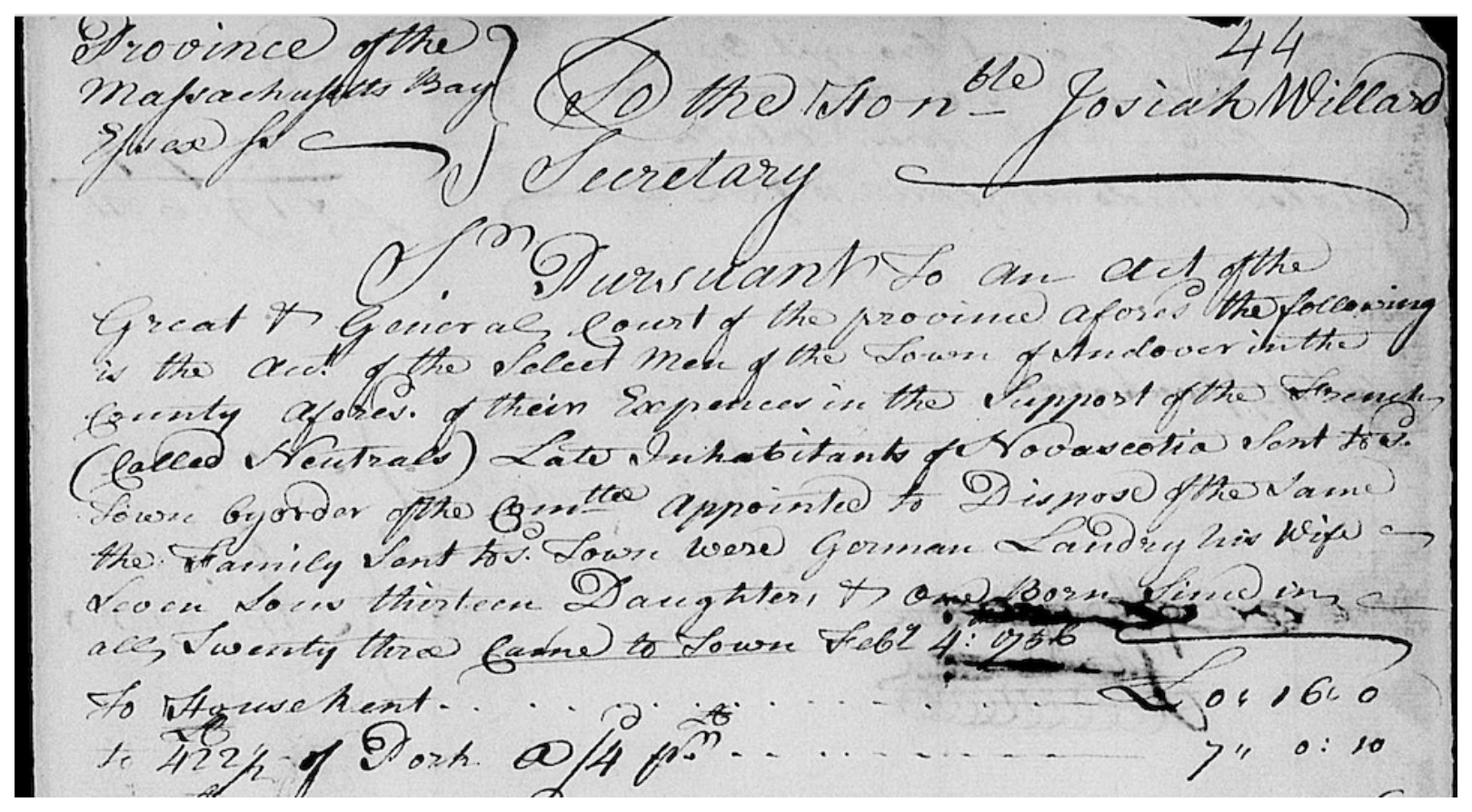

Once permitted to land, the Acadians received temporary quarters on the Boston Common. Shortly, they were parceled out to the surrounding towns. Andover, Massachusetts received 23 Acadians - the extended Germain Landry family plus an infant born shortly after their arrival in Boston - likely Marie-Charlotte Hébert, daughter of Charles Hébert and Marguerite-Monique Landry. The Acadians arrived in Andover on 4 February 1756. 6a

There is evidence that another Acadian couple also resided at least a short time at Andover. A petition filed in early April 1755 by Acadians of several towns to stop the practice of binding out their children was signed by Jacques Hébert and Joseph Vincent of Andover. This is the only known extant record of Joseph Vincent at Andover. He had a wife Marie-Josephe Daigre and two infant children - Marguerite and Joseph. 5

These Acadians were the first Catholics known to set foot in Andover. They were not wanted. After all Andover's own townsman Major Joseph Frye had fought at Beaubassin in the battle for Fort Beauséjour and also in the engagements on the Petitcodiac River and he had commanded Fort Gaspereaux. Some Andover men had died in the Siege of Louisbourg earlier and others had fought with Major Frye. Were these Papists going to side with the French in the French and Indian War, will their financial burden on Andover be high, will there be work for them? The anxiety level among all in Andover was high. Of course, the Acadians did not want to be in Andover either, but they had no choice. Soon Massachusetts authorities passed laws against the Acadians - no public practice of religion, no moving between towns without a license and having the selectmen remove children from Acadian families and place them with local British families. Furthermore, no local families wanted to house these papists.

In mid-1758 at 63 years of age Germain Landry was quite old, infirmed, not capable of any labor and confined to the bed in winter. He needed a great deal of care in winter - more than his wife could perform. Their son Joseph, husband of Marie, was in such a weakly condition that the town was obliged to support him altogether. In addition, there were 11 young children under age nine in three families. 7a

Despite these hindrances, the townspeople of Andover provided care for the Acadians. To help in providing employment, the townspeople lodged the Acadians in three separate areas. 7a Amand Dupuis and his family stayed at the house of Ebenezer Abbott. In the Records for the Board of Selectmen of Andover the first entry dated 14 June 1756 ordered the Treasurer to pay Asa Carlton six shillings for necessaries for keeping house delivered to the French Neutrals at the house of Ebenezer Abbott. 8 9a

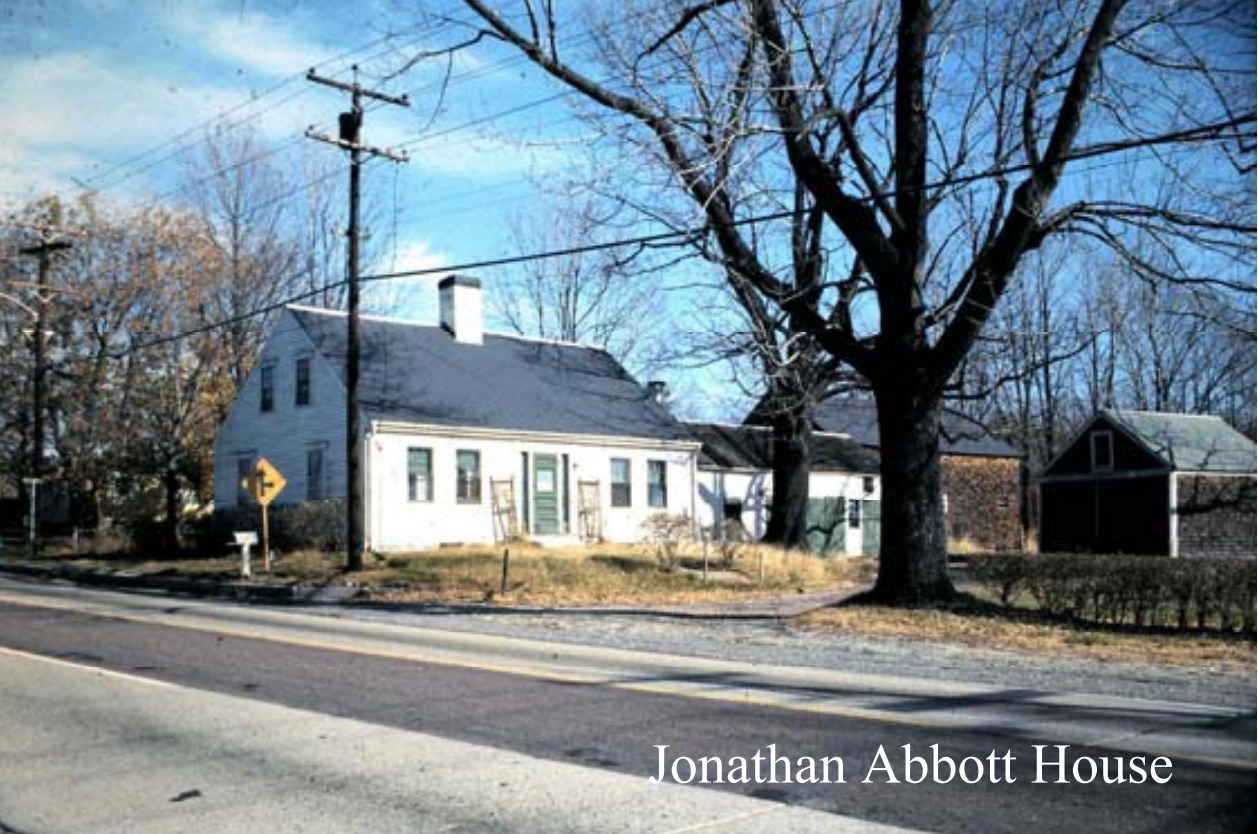

The Jacques Hebert and Charles Hebert families lived at the old Jonathan Abbott house on Ballardvale Road. In 1756 the house was empty as Jonathan Abbott had built a new one across the road. 9a,b When the Hébert families occupied this house, it was part of the extensive Jonathan Abbott farm that extended from Reading Road (today MA Highway 28 or S. Main Street) to Woburn Street and had a very nice spring on it. The major crop grown on the farm was flax and there were woodlands supplying lumber for the houses and buildings.

The house, built about 1730, was of the Cape Cod Cottage type and located about 1/8 mile west of Reading Road (today MA Highway 28 or S. Main Street) and north of Ballardvale Road well into the field. 12 It was later moved to 354 South Main Street when a new home was constructed where it stood. In 1967 the original Jonathan Abbott house was razed and its 1967 location is now the northwest corner of the parking lot of the Faith Lutheran Church. 9b Arcadia Road that intersects Ballardvale Road near the Jonathan Abbott homesites may be a remnant memory of the Acadians living in the area over 250 years ago.

The remaining Acadians, the Landry family, lived in the third location; however, neither the owner nor the location of the home is known. 7a

The Selectmen and residents of Andover provided necessities to the Acadian families from the time of their arrival and throughout their stay in Andover. By 10 April 1756 - only two months after the arrival of the Acadians in Andover - the townspeople had spent over 185 pounds for rent and food.5a During the next four years the Andover Selectmen filed several expense reports detailing the costs of house rent, food and firewood provided the Acadians as well as medical care from Dr. Abiel Abbott. 6b-d 7a,d Various townspeople and merchants assisted the Acadians with their needs including Isaac Abbott, Samuel Phillips, Moody Bridges, Abiel Stevens, John Farnum, Samuel Johnson and the widow Mary Bridges. 6d 9a

Despite the assistance provided by the people of Andover, problems persisted for the Acadians. Several of the Landry family, including Germain and his son Joseph, were ill when they arrived at Andover in February 1756. Dr. Joseph Osgood of the North Parish provided medical assistance as he did to other Andover Acadians during their stay in the town. 9a It was reported in October 1757 that Germain Landry, his son Joseph Landry, Jacques Hébert and Charles Hébert had been sick and indisposed for several months. 6d

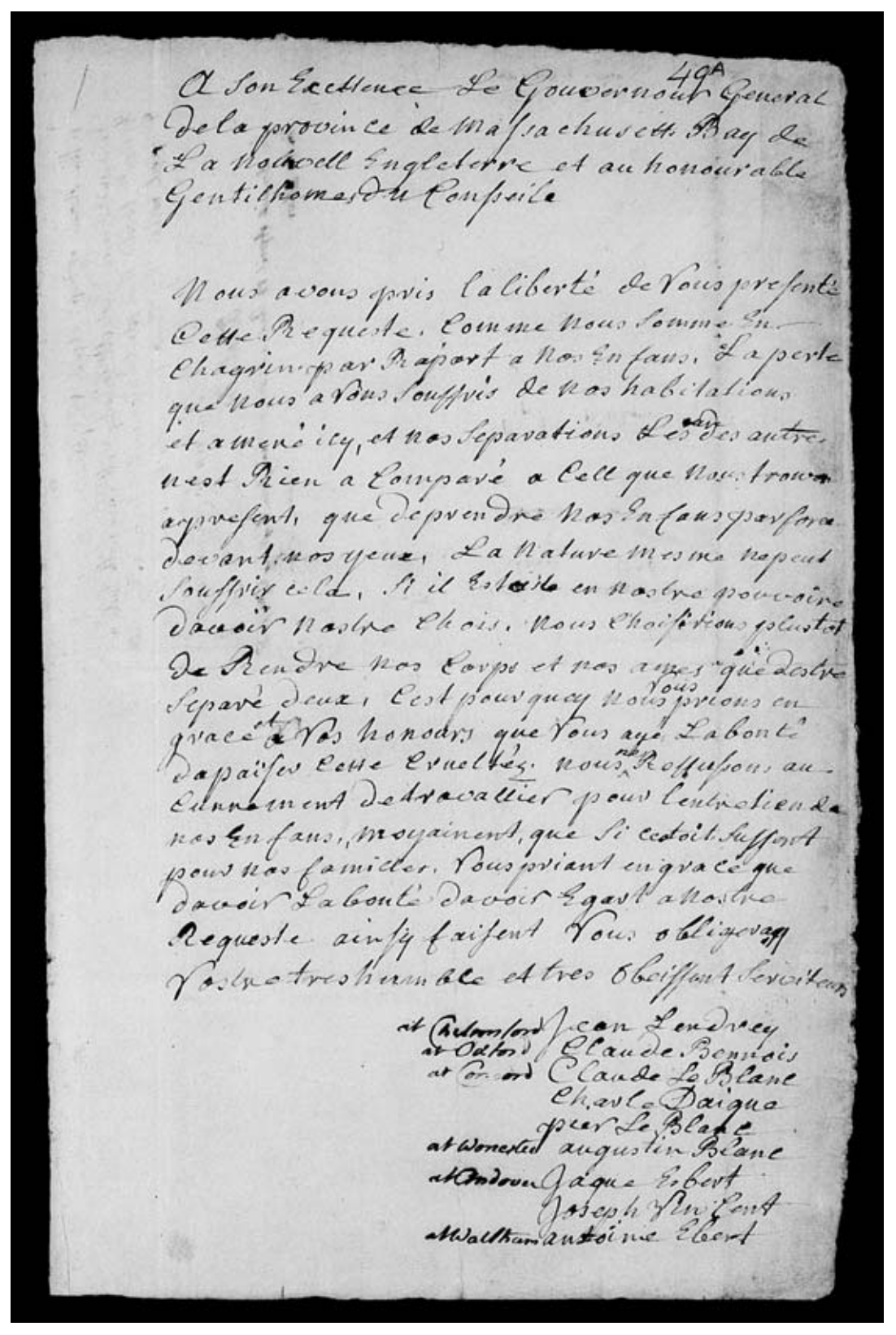

Shortly after the Acadians arrived in Massachusetts, the authorities in Boston passed a law that allowed the Selectmen of the various towns caring for the Acadians to bind out the Acadians including taking Acadian children from their parents and binding them out to townspeople. 10 The townspeople to whom the Acadian children were bound out required the children to do various tasks to earn their subsistence. Acadian parents strongly resisted this due to their strong familial ties and because they did not want their children growing up in British homes, speaking English rather than French and learning British customs. In April 1756 Acadians from various towns including Andover submitted a petition to the Governor and General Court praying for a redress of their grievances. Jacques Hébert and Joseph Vincent signed the petition for Andover. Written in French, the petition brings forth the anguish and deep sorrow felt by the Acadians on losing their children. 5 An English translation is:

To His Excellency the Governor General of the Province of Massachusetts Bay of New England and to the Honorable Gentlemen of the Council

We have taken the liberty to present you this request, as we are in sorrow on account of our children. The loss which we have suffered at your hands, of our houses, and being brought here and our separation from one another is nothing to compare with what we experience at present, that of losing our children by force before our eyes. Nature herself cannot endure that. If it were in our power to have our choice, we should choose rather to lose our body and our soul than to be separated from them. Wherefore we pray your honors that you would have the goodness to mitigate this cruelty. We have not refused from the first to work for the support of our children, provided it were permitted for our own families. Praying you in mercy to have the goodness to have regard to our Petition, thus doing you will oblige your very humble and obedient servants.

at Chelmsford Jean Landrey

at Oxford Claude Bennois

at Concord Claude LeBlanc

Charle Daigre

Pier LeBlanc

at Worcester Augustin Blanc

at Andover Jaque Ebert

Joseph Vincent

at Waltham Antoine Ebert

The 15 April 1756 Order by the Committee considering this Petition required that there be no more binding out of Acadian children. Furthermore, the Order stated that houses be provided for each family so they can remain together and that those Acadians that can work must support their family by their labor. The Selectmen of the towns must assist these Acadians in obtaining jobs at reasonable pay. Furthermore, what the Acadians require beyond what can be obtained by their labor should be provided by the Selectmen. If it became necessary to bind anyone out, it would require the approval of two Justices of Peace in the respective County. 5

In August 1756 the Massachusetts provincial government passed another law forbidding Acadians from moving outside the town or district to which they were assigned unless they possessed a license signed by at least two Selectmen. The punishment for disobeying this law was confinement in the prison for five days without bail and placed on a restricted diet. Any free person could apprehend a "wandering" Acadian. No license could be issued for longer than six days. 10

As elsewhere where the Acadians were deported, the Massachusetts Acadians were not submissive people, but fought for their rights and persisted in their struggles to hold together their families, to keep their religion and to maintain their language and culture.

In the 1600s and 1700s Massachusetts enacted laws forbidding the practice of Catholicism and Catholics were not permitted in the Colony. Catholic priests could not reside in Massachusetts under penalty of imprisonment and execution. It was not until after the War of Independence that Catholics could practice their religion publicly. Since Massachusetts did not permit Catholicism in the 1750s and 1760s, the Acadians could not practice their religion publicly - neither the Mass nor the Sacraments. They had to hold private ceremonies in their houses. When a young couple wished to marry, they had to do it in front of witnesses presided over by a lay person from the community. An adult of the Acadian community had to baptize a young child since no priests were available (referred to as "ondoyé"). The hope was that later a priest would provide the sacramental rites for these marriages and baptisms.

The British in Massachusetts disliked and distrusted the Acadians dropped on their shores. These strange people were French and Catholic for which the British had great prejudice. Furthermore, the French and Indian War was beginning and the horrific news had just been received. The superior military forces of the revered British General Edward Braddock had been defeated on 9 July 1755 by the much inferior French and Indian forces at the Battle of Monongohela and General Braddock had been killed. There was great fear that the French would now overrun the British colonies. Would these Acadians become French spies and assist their "countrymen" during the war?

Although Jonathan Abbott agreed to let the Acadians stay in his empty house, they were a major annoyance to his Puritan character. They not only were tenants in his former house; they were neighbors to his new home. Catholic and French Acadians so close to his home. Despite the strong prejudice of the Puritans and the recent punishing laws, the Acadians overcame all and gained the goodwill of their neighbors in Andover. They were industrious people and very frugal. Although Catholic, they practiced their religion in an inoffensive manner and demonstrated it through their everyday living and good conduct. Even the women worked in the fields pulling flax and harvesting it. 12 13

As the Acadians adapted to their lives in Andover, they toiled for a living, but also continued to have children. Infants born during 1756- 1759 included Jacques Hébert (b. 1758) and Marie-Josephe Hébert (b. 1759), children of Jacques Hébert and Marie Landry; Marguerite Dupuis (b. 1757), daughter of Amand Dupuis and Marie-Blanche Landry and Charles Hébert (b. 1757), son of Charles Hébert and Marguerite-Monique Landry. Other children were born during the 1760s.

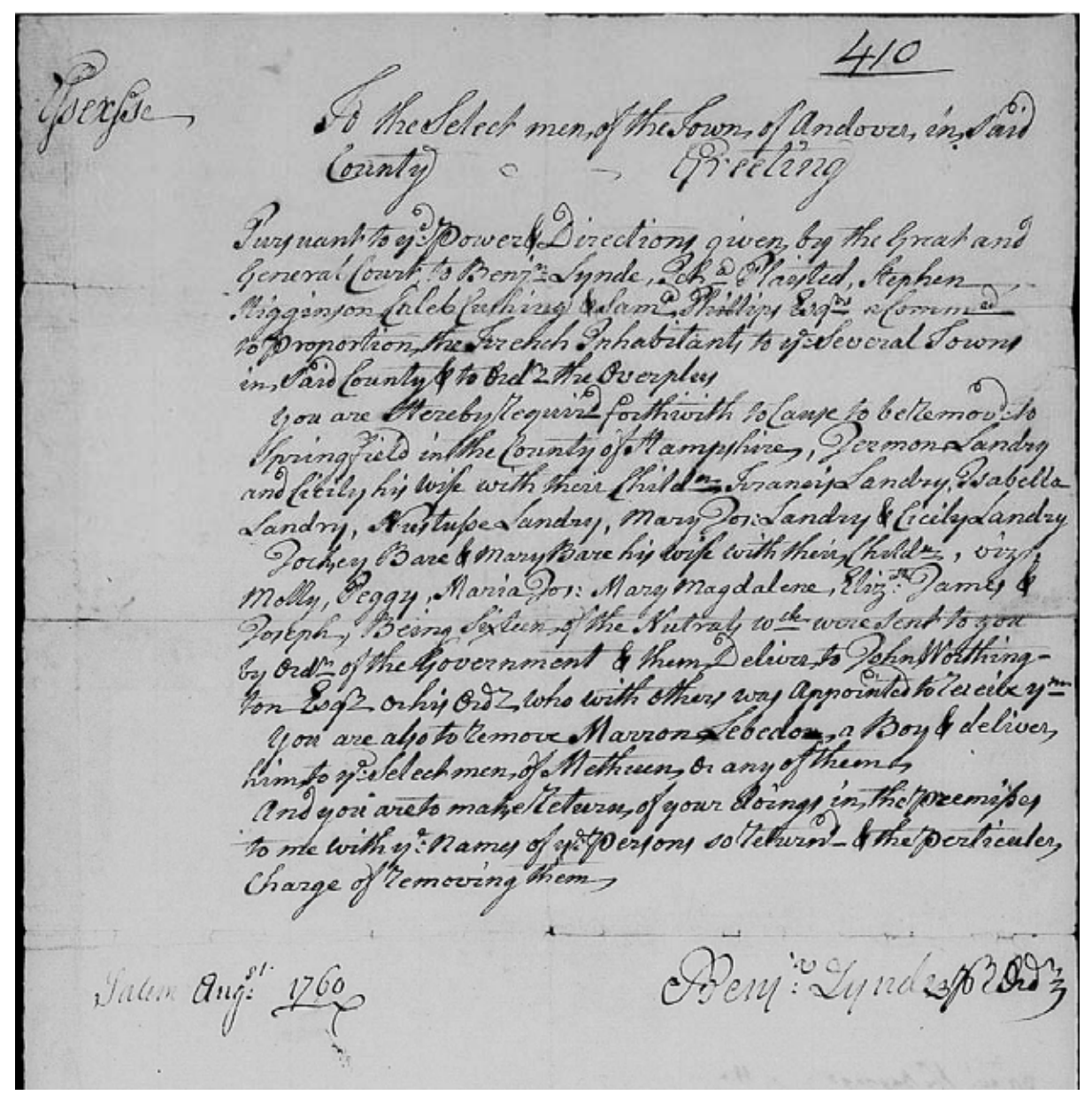

During the decade that the Acadians were held in Massachusetts, the provincial government continually moved groups of Acadians from one town to another for various reasons such as spreading the financial burden among the various towns and requests by Acadians to relocate. In 1760 in order to reproportion the Acadians among the various towns, the provincial government moved sixteen of Andover's Acadians to Springfield, Hampshire County, MA. Located in western Massachusetts, Springfield is approximately 105 miles from Andover. Acadians transported to Springfield were Germain Landry, his wife Cécile Forest, their children François, Elizabeth, Anastasia, Marie-Josephe and Cécile; Jacques Hébert, his wife Marie Landry, their children Marie-Josephe (Molly), Margarite (Peggy), Marie-Josephe, Marie-Magdeleine, Elizabeth, Jacques (James) and Joseph. 7b It was with sadness that Jonathan Abbott and his family watched these Acadians - their friends now - depart for such a faraway place.

The thirteen remaining in Andover were Charles Hébert, his wife Margarite-Monique Landry, their children Mary-Charlotte (Molly, age 4), Charles (age 2), Margarite (Margaret, age 1); Jean-Baptiste Landry; Joseph Landry and his wife Marie; Amand Dupuis, his wife Marie-Blanche Landry and their children Marie-Josephe (age 5), Margarite (age 2), Firmin (9 months). 7c

Interestingly, because the citizens of Andover had a difficult time pronouncing the French names of the Acadians, they "renamed" them with Anglicized names. The Hébert families became the Bear families and the Landry family became the Laundry family. Jacques Hébert was known as Jockey Bear and Germain Landry was called Jermon Laundry. Many of the French Christian names were changed to their English counterparts as Marie became Mary or Molly and Margarite became Margaret or Peggy.

With the 1763 Treaty of Paris ending the French and Indian War many Massachusetts Acadians independently left their assigned towns and moved to Boston. Here on 14 August 1763 were the Germain Landry, Jacques Hébert, Charles Hébert and Amand Dupuis families requesting to be sent to Old France. 14a-d This request was denied to all the Acadians in Massachusetts.

After negotiations in 1765 between the Massachusetts provincial government and James Murray, Governor of Québec, Acadians of the New England colonies were invited to resettle in Québec.

The French and Indian War of 1756-1763 had devastated the economy of Québec. In 1765 to entice as many Acadians as possible to Québec, James Murray offered the Acadians of the New England colonies free land so he could revitalize the Québec economy. Most of these Acadians accepted Governor Murray's offer. They saw in it an opportunity to leave the American colonies which offered no hope to them and their children. This was a chance to begin life anew in a land with a French culture and language, where the inhabitants were Catholic and where many Acadians who had escaped the deportation were settled. Governor Murray granted their resettlement request, but stipulated that they must come at their own expense and they must take an Oath of Allegiance to the British Crown. The Acadians agreed and began arranging how they would pay their transport.

Immediately the Acadians in Massachusetts began making requests to the Massachusetts General Court for financial assistance to go to Québec. Initially, these requests were denied. Acadians who could afford to pay their transportation gathered together and hired a ship to take them to Québec. In early September 1766 two boatloads of Acadians from Boston arrived in Québec. 16 In 1767 the provincial government relented and agreed to pay the transportation costs for Acadians that could not afford to pay their own travel expenses. 17 Additionally, several Massachusetts towns donated money to their Acadians to assist with the travel. Most of the remaining Acadians then left for Québec. By 1775 approximately 1500 Acadians from New England had resettled in Québec. Many of these came from Massachusetts.

All of the Acadians initially assigned to Andover settled in various areas of Québec during the last half of the 1760s.

In 1770 Jacques and Charles Hébert presented Jonathan Abbott with an elaborately carved powder horn as a token of their appreciation for his friendship and his taking care of them and their families. Although there is no primary documentation of the transfer of this gift from Jacques and Charles Hébert to Jonathan Abbott, there are convincing family stories that survive to this day. Furthermore, the powder horn has survived all these years in superb condition and is owned and maintained by the North Andover Historical Society at their headquarters (153 Academy Road; North Andover, MA).

The powder horn is inscribed:

JONATHAN ABBOTAnd also:

His Horn Made in Alens Town April ye 5 1770

I powder With My Brother Ball Most

Hero Like Doth Conquer

ALL

The Band

IS B

The verse of the last three lines in the upper inscription is not unique to this powder horn, but has been found on a number of carved powder horns from this era.

Embellishing the horn are figures of animals as a turtle, a fox, a deer, a ram, dolphins and other creatures. Additionally, the carvings include armies waging battle, soldiers in uniform armed with muskets, sabres and bayonets, artillerymen and field pieces.

Several interesting questions arise about this horn. What is the family lore and tradition about the horn? Who carved the horn? Where is Alens Town? How did the Hébert brothers get this horn to Jonathan Abbott since they were residing in Québec in 1770?

In 1880 Mabel Norcross (Mrs. William) Denholm of Worcester, MA and a Jonathan Abbott descendant, owned and cherished the powder horn. She remained the owner until her death in 1939. 12 13 18 19 At some point after 1939 the Jonathan Abbott horn was taken from Worcester, MA to Marblehead, MA. A New York dealer found the horn in Marblehead in 1968 and brought it to New York. During that same year Mr. Roland B. Hammond, a North Andover antiques dealer went to New York on business and discovered the powder horn. He alerted the North Andover Historical Society who quickly arranged purchase of the powder horn before it could be put on the auction block. 20 21

The rich written tradition of the Jonathan Abbott powder horn dates back over 140 years when Sarah Loring Bailey in 1880 recounted the story of the gift from Jacques and Charles Hébert to Jonathan Abbott in her book Historical Sketches of Andover. 13 In 1964 Bessie P. Goldsmith retold this story in The Townswoman Andover . 12 Likely, Mabel Norcross Denholm, the owner of the powder horn in 1880 and a direct descendant of Jonathan Abbott, provided information on powder horn's unique history to Sarah Loring Bailey. In 1896 at age 59 Annie Sawyer Downs penned a beautiful poem "The Acadians in Andover" that discussed the gift of the powder horn. In discussing the stay of the Acadians in Andover she wrote:

….When they

Back to their homes were sent, sad was the day

And mournful their farewell. They left to show

Their love a carven powder horn, and bow,

And snatches gay of song and dance

And stories strange of distant France. 12 22

Occasionally, a news account on the powder horn will mention that Jacques and Charles Hébert carved the powder horn themselves. This seems very unlikely because of the intricate detail and true artistry in the designs, figures and lettering. A person very experienced in carving powder horns in the late 1700s almost certainly carved it. Very likely this carver was Jacob Gay of Allenstown, New Hampshire. William H. Guthman of Guthman Americana (Westport, CT), a prominent antiques dealer who specialized in historical and military Americana of the Colonial and Federal periods and a national expert on carved powder horns examined photographs of the Jonathan Abbott powder horn. Mr. Guthman determined that the carver of the Jonathan Abbott powder horn was the same person who had carved several of his own powder horns - Jacob Gay. 19 One of the best known and most prolific carvers of the period during the French and Indian War and the American Revolution, Gay's powder horn carving spanned the period 1758 - 1787. Several publications refer to Jacob Gay (Guay) as being an Acadian deported to Andover in 1755 and then resettling in Allenstown, New Hampshire after the Treaty of Paris. No evidence of this has been found.

Three towns in the eastern United States have a name similar to Alens Town: Allenstown, NH; Allentown, PA and Allentown, NJ. Almost certainly the Alens Town referred to on the powder horn is Allenstown, New Hampshire - the home of Jacob Gay.

The literature occasionally mentions that Jacques Hébert and Charles Hébert moved to Allenstown, New Hampshire after the Treaty of Paris (1763) and either carved the powder horn themselves or had the powder horn carved in Allenstown in 1770. This could not have occurred since both Jacques Hébert and Charles Hébert and their families moved to the Province of Québec, Canada in the late 1760s. Jacques Hébert and Marie Landry had a daughter Anastasie born in La Prairie, Québec in 1769. The fact that Jacques Hébert and his family were transferred to Springfield, Hampshire County, MA in 1760 may have resulted in confusion with the name New Hampshire. The distance from Springfield, MA to Allenstown, NH is approximately 140 miles.

In some way Jacques and Charles Hébert contracted with Jacob Gay to carve the powder horn and deliver it to Jonathan Abbott. This likely occurred before the Hébert families left for Québec about 1766. The brothers could have met Jacob Gay at some point in their stay in Andover. Allenstown, NH is only 44 miles from Andover, MA so it would not have been difficult for Jacob Gay to deliver the powder horn to Jonathan Abbott after he had carved it in 1770.

I especially want to thank Ms. Carol Majahad, Executive Director of the North Andover Historical Society, for her vast knowledge and wonderful hospitality when I visited the North Andover Historical Society in August 2019. Carol not only set up a visit outside of normal visiting hours because of my limited schedule, but also assisted me for almost two hours showing me the Jonathan Abbott powder horn and other related Acadian material that the Society held.

References

- Webster, John Clarence; "Lieut.-Colonel Monckton's Journal of 1755" ( The Forts of Chignecto - A Study of Eighteenth-Century Conflict Between France and Great Britain in Acadia ; John Clarence Webster; 1930) p. 115 [Original - Royal Library of Windsor Castle; Windsor Castle; Windsor; SL4 INJ; 44(0) 1753 868286; Cumberland Papers]

- Winslow, John; "Journal of Colonel John Winslow of the Provincial Troops, While Engaged in the Siege of Fort Beausejour in the Summer and Autumn of 1755" ( Report and Collections of the Nova Scotia Historical Society for the Year 1884; Nova Scotia Historical Society; Halifax, NS; Vol. IV; 1885) p. 245 [Original - Library of Massachusetts Historical Society; 1154 Boylston Street; Boston, MA 02215; 617-536-1608]

- Winslow, John; "Journal of Colonel John Winslow, of the Provincial Troops, While Engaged in Removing the Acadian French Inhabitants from Grand Pre and the Neighboring Settlements, in the Autumn of the Year 1755" ( Report and Collections of the Nova Scotia Historical Society ; Nova Scotia Historical Society; Halifax, NS; Vol. III; 1883) (a) pp. 72-74; (b) pp. 90, 94-96; (c) pp. 114-122; (d) pp. 95-96; (e) p. 134; (f) pp. 164-166 [Original - Library of Massachusetts Historical Society; 1154 Boylston Street; Boston, MA 02215; 617-536-1608]

- Delaney, Paul; La Liste de Winslow Explique (Les Éditions Perce-Neige; Moncton, New Brunswick, Canada; 2020) (a) pp. 417-419; (b) pp. 101, 211, 215-217, 236-237, 375

- Massachusetts Archives Collection Database (1629-1799) - Volume 23 (French Neutrals, 1755-1758) (Massachusetts State Archives; 220 Morrissey Boulevard; Boston, MA) Volume 23, Folios 49A-50 (15 April 1756)

- Massachusetts Archives Collection Database (1629-1799) - Volume 23 (French Neutrals, 1755-1758) (Massachusetts State Archives; 220 Morrissey Boulevard; Boston, MA) (a) Volume 23, Folios 44-45 (10 April 1756); (b) Volume 23, Folio 119 (1 June 1756); (c) Volume 23, Folio 229 (10 October 1756); (d) Volume 23, Folios 477-478 (1 October 1757)

- Massachusetts Archives Collection Database (1629-1799) - Volume 24 (French Neutrals, 1758-1769) (Massachusetts State Archives; 220 Morrissey Boulevard; Boston, MA) (a) Volume 24, Folios 47-48 (3 June 1758); (b) Volume 24, Folios 410-411 (August 1760) (c) Volume 24, Folios 367-368 (20 July 1760); (d) Volume 24, Folio 409 (8 September 1760)

- Records of the Board of Selectmen of Andover, Massachusetts (Microfilm copy at North Andover Historical Society; 153 Academy Road; North Andover, MA) Entry dated 14 June 1756

- (a) North Andover Historical Society Newsletter (North Andover Historical Society; 153 Academy Road; North Andover, MA); Spring 1993, pp. 1-2; (b) "Andover Historical Preservation - 354 South Main Street" (Website viewed 24 January 2021 - https://preservation.mhl.org/354-south-main-street

- The Acts and Resolves, Public and Private, of the Province of Massachusetts Bay to Which Are Prefixed the Charters of the Province with Historical and Explantory Notes, and an Appendix - Volume III (Albert J. Wright; Boston, MA; 1878); "Province Laws 1755- 56. Acts Passed at the Session Begun and Held at Boston on the Eleventh Day of December, A. D. 1755 - Chapter 23 - An Act Making Provisions for the Inhabitants of Nova Scotia Sent Hither from That Government, and Lately Arrived in This Province"; p. 887

- The Acts and Resolves, Public and Private, of the Province of Massachusetts Bay to Which Are Prefixed the Charters of the Province with Historical and Explantory Notes, and an Appendix - Volume III (Albert J. Wright; Boston, MA; 1878); "Province Laws 1756- 57. Acts Passed at the Session Begun and Held at Boston on the Eleventh Day of August, A. D. 1756 - Chapter 9 - An Act for the Better Ordering the Late Inhabitants of Nova Scotia, Transported by Order of the Government There."; p. 986

- Goldsmith, Bessie P.; The Townswoman's Andover (The Andover Historical Society; Andover, MA; 1964; 2nd Printing 1970) pp. 16-19

- Bailey, Sarah Loring; Historical Sketches of Andover, Comprising the Present Towns of North Andover and Andover, Massachusetts (Houghton, Mifflin and Company; Boston, MA; 1880) pp. 246-249

- (a) "Liste Generalle des Familles Acadiene Actuellement Repandnees à la Nouvelle Angleterre - Gouvernement de Boston, Province de Massachusset, 14 Août 1763" (Library and Archives Canada; Ottawa, Ontario, Canada) M.G. 5, A-1, Volume 450, Folio 446, pp. 47-48; (b) Massachusetts Archives Collection Database (1629-1799) - Volume 24 (French Neutrals, 1758-1769) (Massachusetts State Archives; 220 Morrissey Boulevard; Boston, MA) Volume 24, Folios 489-490 (14 August 1763); (c) Jehn, Janet; Acadian Exiles in the Colonies (Janet Jehn; Covington, KY; 1977) pp. 164- 165, 171-172, 177-178, 185, 187; (d) Rieder, Milton P. Jr. & Rieder, Norma Gaudet; The Acadian Exiles in the American Colonies, 1755-1768 (Milton P. Rieder, Jr. and Norma Gaudet Rieder; Metairie, LA; 1977) pp. 24-25

- Massachusetts Archives Collection Database (1629-1799) - Volume 24 (French Neutrals, 1758-1769) (Massachusetts State Archives; 220 Morrissey Boulevard; Boston, MA) Volume 24, Folio 558 (14 August 1763)

- Québec Gazette newspaper; 1 September 1766 & 8 September 1766 issues

- The Acts and Resolves, Public and Private, of the Province of Massachusetts Bay to Which Are Prefixed the Charters of the Province with Historical and Explantory Notes, and an Appendix - Volume IV (Wright & Potter Printing Co.; Boston, MA; 1890); "Province Laws 1766-67. Acts Passed at the Session Begun and Held at Boston on the Twenty-Eighth Day of January, A. D. 1767 - Chapter 17 - An Act in Addition to the Several Laws Already Made Relating to the Removal of Poor Persons Out of the Towns Whereof They Are Not Inhabitants"; pp. 911-912, 946-949

- Grancsay, Stephen V.; American Engraved Powder Horns - A Study Based on the J. H. Grenville Gilbert Collection (The Metropolitan Museum of Art; New York; 1945) pp. 41 (No. 5), 85

- Guthman, William H.; Letter to Ms. Martha Larson, Curator, North Andover Historical Society; August 22, 1978 (In possession of the North Andover Historical Society)

- Press Release - April 4, 1969; Thomas W. Leavitt; North Andover Historical Society; North Andover, MA (In possession of the North Andover Historical Society)

- "Old Powder Horn Recovered"; The Eagle-Tribune Newspaper (100 Turnpike Street; North Andover, MA) 8 April 1969

- Downs, Annie Sawyer; Poem: Historic Andover (The Andover Press; Andover, MA; 1896)