Guillaume Petitpas and Angélique Sceau, Wayfarers of the Atlantic

Dans les prisons de Londres et dans le port de Nantes,

pendant de longues années, ils vivèrent dans l'attente

de pouvoir retourner chez eux en Amérique;

on les a bien nommés, les piétons de l'Atlantique.

Ces braves paysans qui venaient du Poitou,

du Berry, de la Touraine, de la Bretagne, de l'Anjou.

Ils avaient tout quitté pour un peu de liberté;

on les a condamnés à vivre en exilés. 1

[In the prisons of London and in the port of Nantes,

long years they waited to return,

to come back to America.

For freedom they had left behind

their lives in Poitou, Britanny,

in Berry, Touraine, in Anjou,

these uncomplaining farmers, now

condemned to exile, far from home,

wayfarers of the Atlantic.]

While these lines by Acadian singer Angèle Arsenault capture the tragic story of most Acadian families, they are particularly apt in reference to our ancestor Guillaume Petitpas. He and his wife Angélique Sceau, deported to France no fewer than three times, certainly earned the nickname of wayfarers of the Atlantic.

Family background

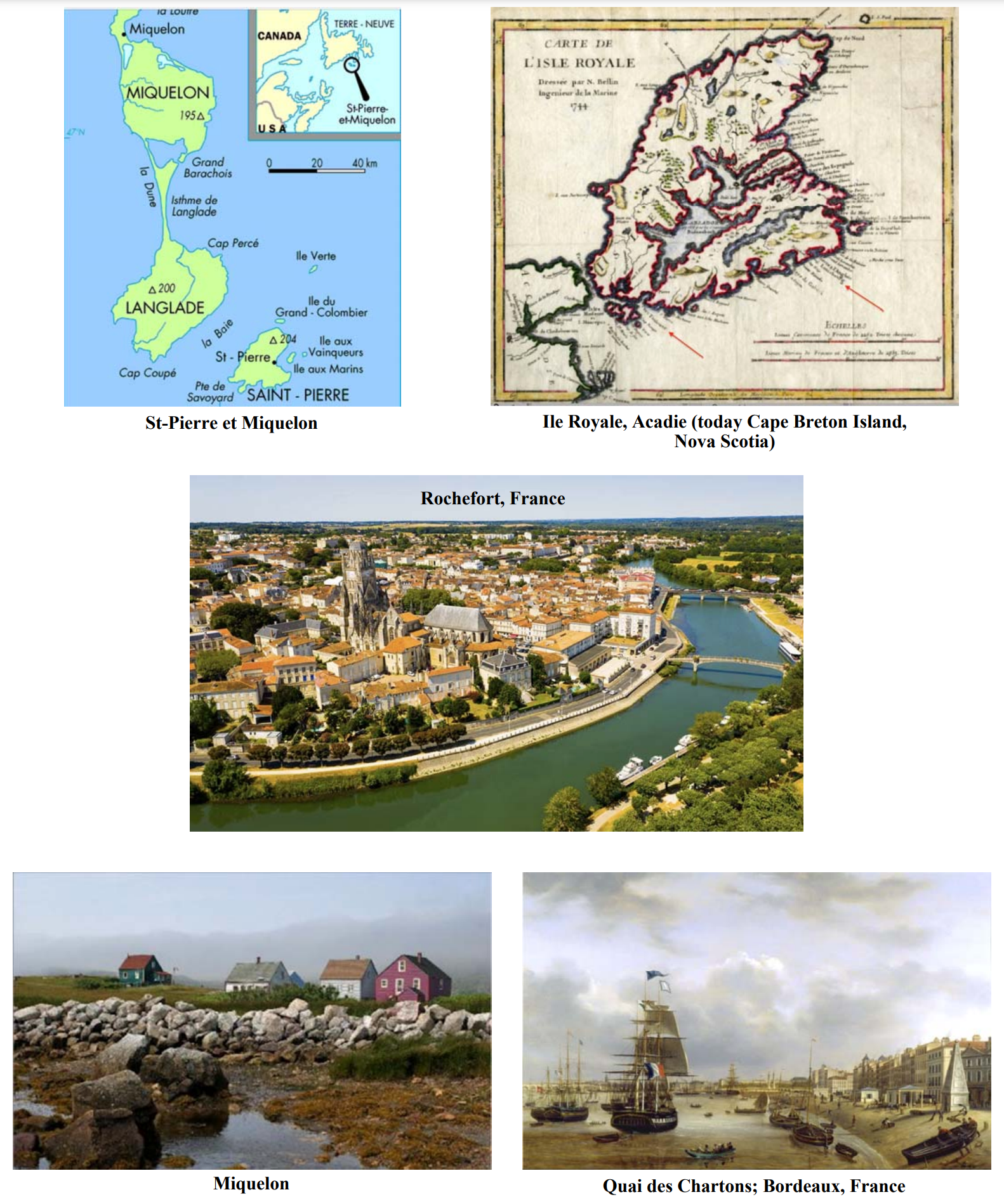

Born in Port Toulouse (now St. Peter's Bay), Cape Breton, around 1735 2 , Guillaume Petitpas was the ninth child and seventh son of Barthélémy Petitpas and Madeleine Coste. His father Barthélémy, son of Claude Petitpas and MarieThérèse, an Amerindian woman, was initially a ship's pilot and later an agent and interpreter with the Micmacs, being fluent in their language. These facts are confirmed in a letter dated August 3, 1734 to France's Minister of the Colonies in Paris:

Barthélemy Petitpas, interpreter of the savages, can no longer live and support his family on his salary of 300 [livres]. His service does not permit him to engage in other occupations. Previously a ship's pilot, he left everything on the strength of promises made to him that he would have reason to be satisfied. No other subject is fitted to be an interpreter. He is obliged to spend the winter in Mirliguech with the missionary to the savages, to teach him the language. 3

The archives report that, following this request, on January 25, 1735 Barthélémy Petitpas was paid 600 livres. It is also recorded that Barthélémy alternated working for the French and the English, thus annoying them both:

Ironically in Barthélémy Petitpas' career, while in 1717 French writer Pierre-Auguste de Soubras described him as “a bad subject, capable of what is most contrary to our interests”, around the same time English official John Doucett accused him of causing “great harm to his sovereign's subjects, by unleashing the savages' anger against them.” 4

In 1745, after Louisbourg was taken by forces from New England, Barthélémy Petitpas was captured and imprisoned in Boston. Massachusetts Governor William Shirley refused all requests for his release, and Barthélémy died in January 1747, still in a Boston prison. In a letter dated July 31, 1747 to the Marquis de Beauharnois, Gouvernor General of New France, Governor Shirley justifies his position in the following terms:

The pilot to whom Monsieur de Caylus refers in his letter to me was named Petitpas [Barthélémy]; he died before I received the said letter. He was originally from Acadia where, for a number of years after the Acadians became subjects of His Majesty under the Treaty of Utrecht, he lived with the family of his father, who was a faithful subject of the British crown, having received favours from that government for his services; thus the son did not have the right to repudiate his allegiance and enter the service of the King of France. I therefore had an undisputed right to retain him; that said, his death puts an end to any discussion about him. 5

At that time, Guillaume Petitpas was a very young adolescent. According to the census conducted in 1752 by the Sieur de Laroque, Guillaume lived with his family at Baie de l’Ardoise, in the parish of Havre-Saint-Esprit, on Île Royale (Cape Breton):

Madeleine Coste, widow of the late Barthélémy Petitpas, born in Port-Royal, aged 54 years. Her six children, two married: Madeleine, aged 34 years, and Joseph, aged 29 years; unmarried: Jean-Baptiste, aged 24 years, Pierre, aged 21 years, Claude, aged 18 years, Guillaume, aged 17 years, and Pélagie, aged 14 years, all born in Port-Toulouse. Her livestock: one bull, four cows, one calf, two hogs, five hens. Owns a dory and a large garden. 6

First deportation: Rochefort (1758)

The taking of the fortress of Louisbourg on July 27, 1758, was to have devastating repercussions for the inhabitants of Île Royale. After this second capture of Louisbourg, more than 3,100 Acadiens were deported to Britain and, from there, to the French ports of Rochefort, La Rochelle and Saint-Malo. The next traces of Guillaume Petitpas and his family can be found in Rochefort, starting in mid-September 1758. The register of the parish of Saint-Louis notes the death of Guillaume's brother Joseph, approximately 36, on October 24, 1758, and of his sister Madeleine, 41, on November 4. Also in the parish of Saint-Louis, on February 12, 1760, Charles Lavigne, the widower of Madeleine Petitpas, married Marie-Anne Lafargue, widow of Joseph Petitpas. As well, according to the records of the Hôpital royal de la Marine in Rochefort, another brother of Guillaume Petitpas, Pierre, died there on October 17, 1758, three days after being admitted.

What happened to Guillaume's mother, Madeleine Coste, enumerated along with her family in the 1752 census at Baie de l'Ardoise? Her fate is uncertain. Tradition has it that she died around 1754 at Baie de l'Ardoise, or at Port-Toulouse, depending on the source. When Guillaume married in 1764, he was declared to be the son of the late Barthélémy Petitpas and of Madeleine Coste, and thus it has been suggested that Madeleine was still living at that time. This evidence is not conclusive, however: although Guillaume's bride, Angélique Sceau, was declared to be the daughter of the late Étienne Sceau and of Marie-Anne Lafargue, both of her parents had died in Rochefort, Étienne Sceau on October 23, 1758 and Marie-Anne Lafargue on November 6 of the same year.

The following few details are known about Guillaume Petitpas' early years in Rochefort. On January 16, 1764, in the church of Saint-Louis in Rochefort, he married Angélique Sceau, daughter of Étienne Sceau and Marie-Anne Lafargue. Angélique was born around 1739 in Havre-Saint-Esprit, the same location where Guillaume's family was enumerated in the 1752 census; thus she, too, was an Acadian who had been exiled from Île Royale. According to Guillaume's marriage certificate, he worked in the port of Rochefort as a day labourer and a carpenter. As well, the fact that Guillaume signed his marriage contract indicates that he was literate.

Certificate of marriage of Guillaume Petitpas and Angélique Sceau, church of SaintLouis, Rochefort,

January 16, 1764 In the year one thousand seven hundred sixty four, on the sixteenth day of January, three marriage banns having been publicized in this church with no civil opposition or canonical bar, the rules and comandments of the Church and of this diocese having been observed, the betrothal having been formalized yesterday before the Church, and the contract having been drawn up by Maître Gaultier, royal notary: after receiving the mutual consent of the contracting parties by proxy, we the undersigned, priest of the Congrégation de la Mission, exercising the duties of curate in the parish of Saint-Louis, Rochefort, conferred the nuptial bessing on Guillaume Petitpas, day labourer and carpenter in the port, of legal age, son of the late Barthélemy Petitpas and of Madeleine Coste, his father and mother, born in Port Toulouse, Île Royale, and living in this city for the past five years; and Angélique Sceau, daugher of the late Étienne Sceau and of Marie-Anne Lafargue, her father and mother, born in the parish of Havre-du-Saint-Esprit, Île Royale, diocese of Québec, and living in this city for the past five years; in the présence of Paul Petitpas, brother of the grooom, Jean Sempau, first cousin of the bride, Hugues Bossol, surgeon […], of Louisbourg, and Jacques Simeau, who with the groom have signed with me, the bride having stated that she does not know how to perform this formality.

[signatures]

Miquelon

The Treaty of Paris, signed on February 10, 1763, finally ended the Seven Years' War (1756-1763), which had been so fateful for the Acadians. Of all its North American colonies, France retained only the tiny islands of Saint-Pierre and Miquelon. A first governor, the Sieur de Dangeac, was appointed on February 23, 1763 and authorized to settle 350 persons, including 50 soldiers, on the islands. However, the islands' small size led to apprehension of overpopulation and ensuing shortages and starvation, as can be seen in the following instructions from the Minister of the Colonies to the new Governor:

With these families, care must be taken to avoid the difficulties experienced on Île Royale after the repossession [the Treaty of Utrecht, 1713]. From the king's stores, all sorts of fishing gear were distributed, most of which were never returned, and which merely gave the inhabitants the benefit of living on the island without being of any use. What is needed on these islands are people suited for fishing, workers, and not inhabitants with no status or occupation ... It is appropriate to reject those who will not be of use. 7

Starting in the summer of 1763, Acadian exiles began to return to these islands, mainly from the French ports of Saint-Malo and Rochefort. It is most likely that Guillaume Petitpas and Angélique Sceau arrived on Miquelon in the summer of 1764. They married in Rochefort in January 1764, and had their first child baptized on Miquelon on February 26, 1765. Miquelon historian Michel Poirier reports that the names of some “fifty Acadians from Île Royale and Acadia, who had been refugees in Saint-Malo (and some in Rochefort) appear on the passenger lists of ships leaving for Saint-Pierre (and Miquelon)” from 1764 until 1766. 8 Suprisingly, there is no mention of Guillaume Petitpas or his family among the 551 Acadians on Miquelon recorded in the May 15, 1767 census conducted by the Sieur de Dangeac; in a footnote to his transcription of this census, Michel Poirier affirms that some families were certainly omitted. 9

Having settled on Miquelon, Guillaume appears to have worked as a fisher and a carpenter, as is noted in the 1785 census. Indeed, at the time of his marriage in 1764, he stated that he was a day labourer and a carpenter in the port of Rochefort. On the island, living conditions were still very precarious, as can be seen from a 1769 report by Joseph Woodmass, who was sent to Saint-Pierre and Miquelon by the Governor of Nova Scotia:

On Miquelon there is a single merchant, with a very bare store. The houses are built of only very small spruce trees, there are a few thin cows, and ewes and lambs brought from France are starving. It costs the government considerable amounts of money to maintain this colony, whose goods are of such mediocre quality and so prohibitively priced that they cannot be sold in the English colonies. In these places, the government not only maintains officers, but is also obliged in winter to provide bread to the inhabitants, at less than cost price. Some Acadians told me that during the first three years they had received only one bread ration from the government, and that, without this assistance, they survived only with great difficulty. A number of them asked me for passports to Nova Scotia. When I refused, they said that at the end of the year they would go there on their own recognizance and at their own risk. 10

In the 1770s, the market for dried cod, shipped mainly to France but also to other French colonies including Guadeloupe, Martinique and Saint-Domingue, gave the islands a significant economic boost. Trade with the New England colonies allowed the Acadians to acquire construction materials such as planks, boards and shingles, as well as flour and tobacco. During this boom, Guillaume and Angélique expanded their family as well, producing eight children between 1765 and 1777:

- Madeleine: baptized on Miquelon on February 25, 1765, godfather Paul Petitpas, godmother Marguerite Sceau; married on Miquelon on July 5, 1787 to Jean Daguerre, son of Jean and of Jeanne Grilhardet of the diocese of Dax, France; died in Bordeaux on January 22, 1853.

- Marie-Josèphe, known as Josette: baptized on Miquelon on March 19, 1766, godfather Jean Coste, godmother Geneviève Sceau; married on Miquelon on November 15, 1787 to Jean Chevalier, son of Georges and of Jeanne Le Breton, of Saint-Pierre-Langers, département of La Manche, France; died in Halifax around 1795.

- Jean-Baptiste: born and baptized on Miquelon on June 14, 1768, godfather Jean-Baptiste Petitpas, godmother Charlotte Lavigne; married around 1795 to Rosalie Vigneau, daughter of Joseph and of Madeleine Cyr, of Miquelon; died at Bordeaux between the 1804 census and August 27, 1805.

- François: Born on Miquelon on January 22 and baptized on January 25, 1770, godfather François Briand, godmother Anne Lafargue; married at Havre-Aubert, Magdalen Islands, on September 16, 1805 to Anne Boudreau, daughter of François Boudreau and of Marie Boudreau known as Castor, of Havre-Aubert; died at Cap-aux-Meules, Magdalen Islands, on Jauary 22 and buried in Havreaux Maisons on January 23,1858 [François is the author's greatgreatgreat-grandfather].

- Paul: born on Miquelon on April 9 and baptized on April 10, 1772, godfather Michel LeBorgne, godmother Jeanne-Suzanne Mancel; died at La Rochelle on September 18 and buried in the parish of Saint-Nicolas on September 19, 1779.

- Pierre: born on Miquelon on Jauary 11 and baptized on January 12, 1774, godfather Pierre Boisramé, godmother Madeleine Hébert; died after 1804.

- Jacques: born and baptized on Miquelon on September 22, 1775, godfather Jacques Arrondel, godmother Madeleine Petitpas; died at La Rochelle on September 15 and buried in the parish of Saint-Nicolas on September 16, 1779.

- Pélagie: born and baptized on Miquelon on October 10, 1777, godfather François Bois, godmother Josette Petitpas; died at La Rochelle on September 27 and buried in the parish of Saint-Nicolas on September 28, 1779.

On November 1, 1776, a new census of the islands of Saint-Pierre and Miquelon provides some details about the family and its possessions:

Guillaume Petitpas, 40; his wife Angélique Sceau, 35; their children: Madeleine, 11; Josette, 10; Jean-Baptiste, 8; François, 7; Pierre, 5; Paul, 3; Jacques, 2; owns a house, a halfshare in a pebble beach shoreline where fish catches are landed, a quartershare in a barn 11 , and a halfshare in a dory. 12

For these islanders, life could have flowed on, slowly and surely, through waves and undercurrents, with each day of patient labour and hard earned rest bringing a little more comfort to evergrowing households - if it hadn't been for political ambitions in high places. By an accident of history, aspirations of independance in the American colonies meant exile once again for the Acadian settlers on Miquelon.

Second deportation: La Rochelle (1778)

In 1775, Britain's Thirteen Colonies in North America initiated a revolutionary war with the old country. The war would culminate in the Declaration of Independance on July 4, 1776 and official British recognition of the United States of America in 1783. On February 6, 1778, France entered the conflict on the side of the colonies, effectively declaring war on Britain. On October 1, 1778, the British took Saint-Pierre and Miquelon and deported the inhabitats once again to France.

The distress among these luckless Acadians can only be imagined, reexperiencing as they did the nightmarish events of 1758, 20 years previously. Once again, the British soliders left nothing to chance:

Whatever was not pillaged was set afire: 237 houses, 126 fishing shelters, 89 storehouses, six bakeries, 79 stables, 38 barns and a great many dories. Even the wharf and the beaches where fish catches were landed were destroyed, and the inhabitants herded aboard with not even an opportunity to save their ragged clothing, the houses being set on fire the moment the occupants had left. 13

Dr. Paterson, surgeon to the British troops aboard H.M.S. Pallas, in a letter written on October 19, 1778 from St. John’s, Newfoundland, writes:

We arrived on the 15th and took possession of the island. On the 16th, we marched all the inhabitants aboard, as they were, to ship them back to France; after which we seized two French ships and loaded them with the most valuable items we had found on the island, valued at 12,000£; otherwise, if we had had enough ships to take all the goods, we could have had three times that amount. As soon as the inhabitants had been taken aboard the ships, we burned the town, the houses, the storehouses and other remaining buildings, along with several thousand pounds of fish. 14

For the second time, now accompanied by his family, Guillaume Petitpas crossed the Atlantic toward the Old World. After landing at the port of La Rochelle in November 1778, they settled (or were settled) in the parish of Saint-Nicolas in La Rochelle. Other groups of Acadians would be located in Nantes, Rochefort, Cherbourg and Saint-Malo.

For Guillaume and Angélique, as for so many families, this repeated exile was characterized not only by hardship and want, but also by mourning. On September 15, 1779, they lost their son Jacques, 4; four days later, on September 19, they buried another son, Paul, 7; and on September 27, little Pélagie, 2, passed away. And yet, beyond suffering, life goes on: soon three more children, including twins, took the place of those who had died:

- Anne-Pélagie: born at La Rochelle on January 12 and baptized on January 13, 1780 in the parish of Saint-Nicolas, godfather Pierre Letiecq, godmother Anne Lavigne; died at La Rochelle on March 9 and buried March 10, 1784 in the parish of Saint-Nicolas.

- Louis-Toussaint: born and baptized at La Rochelle on March 22, 1782 in the parish of SaintNicolas, godfather Toussaint Letiecq, godmother Madeleine Petitpas; died at La Rochelle on December 27 and buried on December 28, 1782 in the parish of Saint-Nicolas.

- Angélique: born and baptized at La Rochelle on March 22, 1782 in the parish of Saint-Nicolas, godfather Jean-Baptiste Petitpas, godmother Marie-Anne Briand; became a nun and died at the convent of the Filles de Marie Notre-Dame in Bordeaux on December 19, 1850.

Here again, except for baptisms and burials in parish registers, little information remains about the living conditions of Guillaume and his family during their time of exile in La Rochelle. Historian Michel Poirier summarizes the life of the former inhabitants of Miquelon deported to La Rochelle as follows:

For a few years, then, these impoverished refugees were again in touch with family members who had been deported from Acadia and had remained in France, not joining the 1767 emigration. They were granted 12 sols per adult per day and six sols per child per day. For five years, these farmer-seafarers experienced unfamiliar idleness, although replacing French sailors, conscripted by the military navy, on coastal shipping routes. 15

Return to Miquelon

On September 3, 1783, the signature of the Treaty of Versailles, recognizing the independence of the United States of America, also returned the islands of Saint-Pierre and Miquelon to France. A decision was made to reestablish the small colony. A letter was circulated in the main port cities of France, inviting the Acadian refugees to attempt, once again, the adventure of the Americas. There were conditions, however:

Only those persons who could make themselves useful would be transported at the king's expense and supplied with provisions for six months or one year. Nearly 1,250 persons signed up, most of them originally from Acadia, Île Saint-Jean or Louisbourg: 717 in La Rochelle, 420 in Saint-Malo, 26 in Lorient, 23 in Nantes, 27 in Cherbourg, 21 in Bayonne and eight in Granville. 16

Still apprehensive that too large an influx of immigrants would hinder the islands' development, Monsieur Marchais, Shipping Comissioner at La Rochelle, made the following request:

that the number of persons from La Rochelle, particularly unproductive mouths, be considerably reduced; this reduction affects families with six or eight children. [Although] the proposal appears to be very strict, children from the age of 10 can work on the beaches where fish catches are landed. 17

Eventually 120 refugees from La Rochelle set sail again for the islands of Saint-Pierre and Miquelon. According to the census conducted on Saint-Pierre on December 23, 1783, many families had already returned there. The situation must have been the same on Miquelon, where, with the exception of a single entry in 1783, the parish registers begin again on April 18, 1784.

It can be seen that Guillaume Petitpas and his family were still in La Rochelle on March 10, 1784, when their young daughter Anne-Pélagie was buried in the parish of Saint-Nicolas. Thus it was that same year, 1784, that the family crossed the Atlantic for the fourth - and, unfortunately, not the last - time. This time again, Guillaume, Angélique and their six remaining children were obliged to start from scratch. According to the census conducted on Miquelon on November 12, 1785, Guillaume had taken up his former trades again, and the family was relatively well off:

Petitpas, Guillaume, 52; Sceau, Angélique, his wife, 46; their children: Jean-Baptiste, 17, François, 15, Pierre, 13, Madeleine, 20, Joséphine, 18, Angélique, 3. Notes: A fisher and a carpenter, he has a halfshare in a dory that he uses for fishing. He and his children work at the beach where fish catches are landed. He has a garden. 18

Guillaume's nephew Jean-Baptiste Petitpas, the son of his brother Joseph who had died at Rochefort in 1758, occupied the neighbouring property with his wife Marie Vigneau and their three sons. On July 5, 1787, Madeleine, the oldest of Guillaume's and Angélique's children, was the first to marry, in the church of Notre-Dame des Ardilliers on Miquelon, taking as her husband Jean Daguerre, originally from Saint-Pierre d'Arraute in the diocese of Dax, Navarre, France, son of the late Jean Daguerre (or Daguère) and of Jeanne Grilhardet. A few months later, on November 15, it was the turn of her younger sister, Marie-Josèphe, known as Josette or Joséphine, who married Jean Chevalier, son of Georges Chevalier and of Jeanne Le Breton, originally from Saint-Pierre de Langeac, Normandy, France. One of the witnesses who signed the parish register that day was Paul Petitpas, Guillaume's brother and Josette's uncle. Only 10 days later, on November 25, 1787, Paul, who had not married, was drowned off Miquelon at age 48.

While the taking of the Bastille in Paris on July 14, 1789 triggered significant upheavals in France, its repercussions were felt more slowly on Miquelon. In 1792, the Assemblée générale of the commune of Saint-Pierre and Miquelon was established. It is noted that, in general, the residents of Saint-Pierre had more republican sentiments than the inhabitants of Miquelon, most of whom were Acadian and remained attached to their religion and their institutions. On April 12, 1793, anxious at the spread of revolutionary ideas on their island, a group of some 250 Acadians left Miquelon for the Magadalen Islands, accompanied by their parish priest, the Reverend Jean-Baptiste Allain, who had refused to take the constitutional oath required of clergy by the revolutionaries. This group of people would form the core of the population of the Magdalen Islands.

Guillaume Petitpas, however, decided to remain with his family on Miquelon, where misfortune soon caught up with him again. On February 1, 1793, revolutionary France declared war on Britain; once again, the conflict would have consequences for the colonies in America.

On May 14, 1793, British forces led by Admiral King attacked the islands. The French troops were obliged to surrender and depart for France. By contrast with the events of 1778, this time the British did not destroy the colony but determined to rally the population, then numbering some 1,200 inhabitants, to their cause. This attempt failed in the face of the Miquelonnais' persistent attachment to France, and the British authorities decided to deport the inhabitants of Miquelon, first to Halifax, Nova Scotia, and then back to France. For Guillaume Petitpas and his family, this decision meant deportation and exile once again.

Third deportation: Halifax (1795) and Bordeaux (1797)

On September 14, 1794, all the inhabitants of Miquelon were taken to Halifax, where most of them were employed on fishing vessels and transport ships. During these years of captivity in Halifax, around 1795 Guillaume and Angélique had the sorrow of losing their daughter Josette, who had married Jean Chevalier. Sir John Wentworth, Lieutenant-Governor of Nova Scotia, also attempted to assimilate this French-speaking Roman Catholic population, and failed. Stating that he “could no longer hope to come to any terms with them”, he, too, decided to send the Acadians off to France.

Guillaume Petitpas and his family boarded the ship Washington, and reached Bordeaux on July 20, 1797. For Guillaume and Angélique, this would be the fifth, and last, Atlantic crossing.

On arriving in Bordeaux, like many other Acadian refugees, the family settled on the Quai des Chartrons, now in the neighbourhood of Mériadec, in what had been the monastery of the Carthusian monks, dispossessed by the French Revolution. A list of the occupants drawn up by a monastery official shortly after the arrival of the exiles from Miquelon enumerates 83 persons in 22 families. The names of Guillaume Petitpas, his wife and three children appear at the top of the list. Here, too, living arrangements were precarious, given that the Acadians had been able to bring very few goods with them. In a brief submitted in 1802, Claude Goueslard, a former inhabitant of Saint-Pierre who was deported to Bordeaux, describs the pitiable living conditions of the refugees from Miquelon at that time:

Imagine, citizen minister, a family of persons of all ages and both sexes, taken from their home some eight years previously, and during that time being transported to various countries where they were almost always without work, having nothing more to live on than assistance that the government deigned to provide. One need not offer a lengthy argument to convince you of the extent of their needs. I could swear to you that some of them would be in need of everything. You cannot imagine the extremity to which the elimination of food rations has reduced most of these families. Some of the children are practically naked. As well, to ensure that morality is maintained it will be necessary to provide them with beds and bedcovers. To convince you of this fact one need only point out that many of these people sleep on beds belonging to the Republic. Many do not have a single kettle in which to make soup, most of them using only earthen pots. 19

The end

For Guillaume Petitpas, this life was drawing to a close. After so many deportations, so many times of having to begin again with nothing, his only hope was for an old age that would be, not necessarily happy, but peaceful, with the few of his children who were still living. What became of them is related below.

In 1804, Guillaume Petitpas signed a document setting out the names and circumstances of the farming and fishing families from the islands of Saint-Pierre and Miquelon living in Bordeaux. The first lines of this enumeration read as follows:

Petitpas, Guillaume, 70; Sceau, Angélique, his wife, 59; François, their son, “in prison in England”, 27; Pierre, their son,”signed on to a privateer vessel”, 26; Angélique, their daughter, 17. 20

A few months later, on August 27, 1804 (or Fructidor 9, year XII, according to the republican calendar then in use in France), Guillaume died in his lodgings in the former Carthusian monastery, as is witnessed in the following death certificate, dated September 2, 1804:

Death certificate of Guillaume Petitpas, resident of Bordeaux, Fructidor 15, year XII of the Republic (or September 2, 1804)

Drawn up on this date: Death certificate of Guillaume Petitpas, deceased on the ninth day of this month at eight o'clock in the morning, born on Île Royale, aged seventy five years, husband of Angélique Sceau, both deported from the island of Saint-Pierre de Miquelon, living at the former Carthusian monastery, section 6, according to the statement made by citizens Pierre Abraham, Inspector of the general cemetery, and Jean-Baptiste Briand, also deported from the same island and living at the former Carthusian monastery, who have signed the document filed in the archives of the civil registry office. Recorded by myself, Assistant to the Mayor, acting as Registry Officer.

J. M. Pouchan

Angélique Sceau, Guillaume Petitpas' widow, died a few years later, October 4, 1812. Her death certificate names her as Catherine Sceau:

Death certificate of Angélique Sceau, resident of Bordeaux, October 5, 1812

On the fifth day of this month, a document was filed by the Commissioner of Death Records indicating that Catherine (sic) Sceau, aged approximately seventy three, born in the parish of Havre-du-Saint-Esprit on Île Royale, diocese of Québec, widow of Guillaume Petitpas, ship's carpenter, living in the former Carthusian monastery, daughter of the late Étienne Sceau and of Marie-Anne Lafargue, died yesterday evening at four o'clock, according to the statement made by Jean Graule, concierge of the said former monastery and living there, and Louis André Cézenac, day labourer and also living in the same former monastery, witnesses of legal age who have signed the said document filed in the archives of the city registry office.

J. Labrouef, Assistant to the Mayor

After so many departures, displacements and deaths, Guillaume Petitpas and Angélique Sceau now rest in the old Cimetière Nord in the Bruges district of northern Bordeaux, under headstones that have long since forgotten their names.

Descendants

As has been seen, the marriage between Guillaume Petitpas and Angélique Sceau produced eleven children, five of whom - Paul, Jaques, Pélagie, Anne-Pélagie and Louis-Toussaint - died young during the exile in La Rochelle. The six others lived to adulthood, and some of them had descendants of their own, as summarized below.

About Madeleine, the oldest, only her date of baptism, February 26, 1765, is known. The register of the parish of Notre-Dame des Ardilliers on Miquelon does not indicate her date of birth. Was she born on the same day she was baptized, a few days earlier, or during the ocean voyage to Miquelon? No one knows. It is known that on July 5, 1787 she married Jean Daguerre, then in his forties, born on June 27, 1741 in Saint-Pierre d’Arraute (today Arraute-Charritte), Pyrénées Atlantiques, son of Jean D'Aguerre and of Jeanne Guilhardet. This couple, deported to Halifax and then to Bordeaux, are shown on the 1804 census of Acadians in Bordeaux as having five children, then aged between 9 and 2. Jean Daguerre died in Bordeaux on January 3, 1806. Madeleine's name appears on the list of Miquelon refugees eligible for public assistance in Bordeaux in 1832. She died there, at 22, rue Séraphin, on January 22, 1853 “at nine o'clock in the morning”, as her death certificate notes.

It is recorded that Madeleine's younger sister Marie-Josèphe, also known as Josette or Joséphine, was baptized on Miquelon on March 19, 1766 and, on November 15, 1787, married Jean (Le) Chevalier, born in Saint-Pierre-Langers, diocese of Avranches, Normandy, on December 6, 1759, son of Georges Le Chevalier and of Jeanne Le Breton. Josette apparently died around 1795, undoubtedly during the imprisonment in Halifax; Jean died in Bordeaux in 1803. The 1804 census lists their three children, then aged 16, 12 and 8; with the exception of the oldest boy, who had signed on to a ship, the children apparently lived with their aunt Madeleine.

Like his father Guillaume, the oldest son Jean-Baptiste, born on Miquelon on June 14, 1768, was a seafarer and ships' carpenter. Around 1795, undoubtedly during the imprisonment in Halifax, he married Rosalie Vigneau, born on Miquelon on July 19, 1772, daughter of Joseph Vigneau and of Madeleine Cyr. They had four children, all of whom died young in Bordeaux between 1798 and 1805. Named in the 1804 census, Jean-Baptiste had died by the time his son Zéphirin was buried on August 27, 1805. Rosalie remarried, twice, and returned in June 1816 to Miquelon, where she died on August 14, 1859.

François, born on Miquelon on January 22, 1770, went with the family to Halifax and then to Bordeaux, and eventually crossed the Atlantic again around 1803, joining relatives on the Magdalen Islands. The 1804 census conducted in Bordeaux describes François as a “prisoner in England”; his 1805 marriage certificate indicates that he had been living on the Magdalen Islands “for two years”; and an 1806 list of Magdalen Islander residents states that he had settled in Cap-aux-Meules in 1804. On September 16, 1805 in Havre-Aubert, he married Anne Boudreau, born on the Madgalen Islands around 1787, daughter of François Boudreau and of Marie Boudreau known as Castor. Anne died some time between January 13, 1833 and January 22, 1840, a period for which parish registers are missing. François died in Cap-aux-Meules on January 22, 1858, the last surviving child of Guillaume and Angélique. François and Anne had eight children, who would ensure that the family line continued, mainly on the Magdalen Islands and on the North Shore.

About Guillaume's and Angélique's third son, Pierre, born on Miquelon on January 11, 1774, only the first part of an adventurous life is known. On August 7, 1798 in Bordeaux, Pierre was hired as a helmsman on the ship La Résolue. As the Napoleonic Wars loomed between France and Britain, he was captured by the British on October 14 that same year and imprisoned in Portsmouth. Repatriated to France aboard the Jenny and Sally, he landed at Cherbourg on April 17, 1802. The 1804 census conducted in Bordeaux states that he had once again “signed on to a privateer vessel”. There is no further record of his life.

What happened to Angélique is better known. Born during the exile in La Rochelle on March 22 1782, as the youngest and nevermarried child it was her duty to take care of her parents, with whom she lived until they died. On January 6, 1824, she entered religious life as Sister Sainte-Angèle, of the Filles de Marie Notre-Dame in Bordeaux, a congregation reestablished only then after having been dissolved in 1792 by the French Revolution:

In the year one thousand eight hundred twenty four, on the sixth day of January, did take the religious habit of the order of Notre-Dame, to be admitted as a member of the sisters of the quire, Miss Angélique Petitpas, aged 42 years, born in La Rochelle, legitimate daughter of the late Guillaume Petitpas and of Angélique Sceau, inhabitants and landowners on the island of Saint-Pierre de Miquelon, from the hands of Monsignor the Archbishop of Bordeaux and Reverend Mother Marie-Victoire-Bertrande-Cyrille de Brancan d’Estoup, known as Sister SainteThérèse, superior of this house of Notre-Dame. The said young lady took Sister Sainte Angèle as her name in religion; the following have signed:

[signatures] 21

Angélique became a professed sister on January 6, 1826. On December 14, 1827, she was promoted to a position as a chapter mother, becoming Mother Sainte-Angèle. 22 She is enumerated in 1841 and 1846 at the Filles de Marie Notre-Dame convent, 49, rue du Palais-Gallien in Bordeaux, where she died on December 19, 1850 “at seven o'clock in the morning”.

References

- Arsenault, Angèle (1943-2014), Grand-Pré , song composed for the 1994 Acadian World Congress.

- The date of Guillaume Petitpas' birth varies from one census to another: 1735 (1752 census); 1736 (1776 census); 1733 (1785 census); 1734 (1804 census).

- Saint-Ovide de Brouillan et Le Normand to the Minister, Île Royale, August 3, 1734, Archives des colonies , série C11B, vol. 15, fol. 12 et 12v.

- Pothier, Bernard, Dictionnaire Biographique du Canada , Québec, Presses de l'Université Laval, 1974, tome III, pages 554-555.

- Quebec Legislature, Collection de documents relatifs à l'histoire de la Nouvelle-France , Québec, Imprimerie A. Côté et cie, 1884, tome III, page 379.

- Census conducted by the Sieur de Laroque, Île Royale, 1752, page 12.

- Letter from France's Minister of the Colonies to the Sieur de Dangeac, February 1763, Paris, Archives nationales , F3 54, f 39; 467.

- Poirier, Michel, Les Acadiens aux Îles Saint-Pierre et Miquelon , Moncton, Les Éditions d'Acadie, 1984, page 30.

- Poirier, Michel, op. cit. , pages 201-218.

- Colonial official records, London UK, published by Placide Gaudet, Rapport des archives publiques du Canada , 1905, tome 2, pages 225-227.

- Wiktionnaire indicates that the old French term "chafaud" means a building to store hay or grain.

- Poirier, Michel, op. cit. , page 283.

- Ibid. , page 98.

- Published in The London Chronicle , London UK, November 17, 1778.

- Poirier, Michel, op. cit. , page 99.

- Ibid.

- Ibid. , page 100

- Poirier, Michel, op. cit. , page 369.

- Poirier, Michel, op. cit. , page 126.

- Ibid. , page 401.

- Communication from Sisiter Cécile Amalric, Archivist, Compagnie de Marie-Notre-Dame, Bordeaux, March 7, 1997.

- Communication from Sisiter Colette de Boisse, Archivist, Compagnie de Marie-Notre-Dame, Bordeaux, April 9, 2018.