Acadians in Madawaska - Their Journey and Struggle

On 28 July 1755 British Governor Charles Lawrence signed a document forever changing the lives of thousands of Acadians. On this date he ordered that all Acadians be deported from Acadia. Many reasons have been suggested for the deportations including: the Acadians were French and Catholic, the Acadians would not sign an unqualified Oath of Allegiance to the King of England and the British wanted the Acadian farms for British settlers. Although each of these probably played a role in the decision to deport them, the more significant reason likely was that Britain and France had been fighting in Europe and North America for over a century and another war was looming. With some skirmishes occurring in the early 1750s, the Seven Years War (also known as the French and Indian War) began in earnest during 1756. Sensing war was inevitable, Lawrence feared that the Acadians may support the French during any fighting in Acadia.

Since the Treaty of Utrecht in 1713, Acadia belonged to Britain yet most French Acadians chose to stay in Acadia. They only wanted to live in peace on their farms and not choose between the French or the British. In their minds they were Acadian - not French or British. Both the British and French, however, continually harassed and threatened the Acadians - trying to gain their allegiance and support. The British threatened the Acadians that they had to sign an unqualified Oath of Allegiance to the King of England or leave Acadia. The French had several priests, including Abbé Jean-Louis Le Loutre, threaten the Acadians by telling them that they must move to nearby French territory or the priests would have the local Mi'kmaq people attack them.

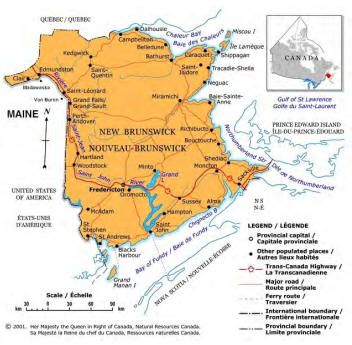

By 1749 some Acadians had taken the harassment of their priests seriously and began migrating to Île StJean (today Prince Edward Island), Île Royale (today Cape Breton) and southern New Brunswick. They joined a small number of their cousins who had settled in these areas many years before. On 13 August 1755 the first Acadians were deported from the Beaubassin area. For the next 8 years Acadians continued to be deported to the Atlantic seaboard colonies of North America, to France and even to England. More Acadians began to flee - especially to the French territory of New Brunswick.

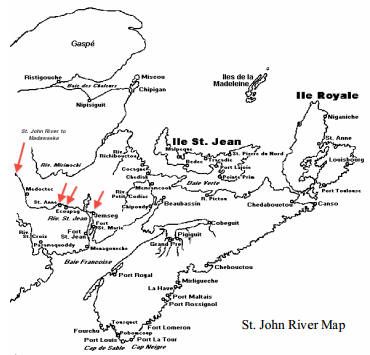

A number of years earlier a small group of Acadians had settled on the lower St. John River in New Brunswick near old Fort Latour. By 1701 fifty people lived in this area. In 1732 over eighty Acadians from fifteen families fled the British authorities in Acadia and resettled on the St. John River near today's Fredericton, New Brunswick. They called their village Sainte-Anne-des-Pays-Bas or Ste-Anne's Point. Their numbers continued to grow as other villages sprang up nearby. By 1755 over two thousand Acadians were at Grimrose, Jemseg, Nashwack, Ecoupag and Ste-Anne.

The British under Colonel Robert Monckton continually raided the lower St. John River, burning down Acadian villages and massacring settlers, but the Acadians clung to their new lands in the only significant Acadian settlements in New Brunswick. In 1759 Monckton's Rangers burnt the village of Ste-Anne to the ground. The surviving Acadians fled to nearby forests where they lived for the next eight years. The Acadians' resourcefulness, their strong friendship with the local Native Americans and the help of Charles des Champs de Boishébert, the local French military commander, contributed significantly to their survival. Living each day was a constant struggle.

In 1763 the French and Indian War ended and the Treaty of Paris was signed. The Acadians were now free to migrate to new places. Being very poor and having no means to pay for transportation, many Acadians languished for several more years petitioning colonial governments to pay for their transport to Québec, Acadia, Louisiana, Saint-Domingue or elsewhere. The Acadians hiding in the woods of New Brunswick returned to their old homes near SteAnne only to find them being occupied by English colonists. Even the town of Ste-Anne had acquired a new English name - Fredericton.

Resilient as always, the Acadians packed their meager belongings and moved further up the St. John River - to Ecoupag, French Village and Kennebeccassis. Here they settled, cleared land again and hoped to have land grants approved by the British government. Government officials in Québec and New Brunswick promised to protect the Acadians and their new lands.

A few of the Acadians who had been coureurs des bois (i.e., trappers, traders, woodsmen) became "express carriers". Traveling overland and by water, they kept the lines of communication open between Halifax and Québec. Thus they came to know the upper St. John River and its fertile valleys well.

With the end of the American Revolution in 1783 many English loyalists living in the American colonies fled to British Canada for safety and protection. They were harassed by the victorious Americans and did not feel safe in the Colonies. Some came to New Brunswick between 1782 and 1785 and settled the same lands on which Acadians had lived for twenty years.

Even though they had just been pushed from their homes in the Colonies, they were not sympathetic to the Acadians who had undergone an even worse experience. Without delay the English loyalists became hostile toward their Acadian neighbors - burning fences of the Acadians, stealing animals, destroying crops and opening Acadian cellars during the worst frosts of winter to freeze stored vegetables. They even evicted the Acadians from their own lands. To the English colonists, the Acadians were French squatters even though the Acadians had settled these farms two decades earlier. The belligerent attitude of the new English settlers upset Canadian authorities as they wrestled with solving this problem.

Governor Parr of Nova Scotia tried to help the Acadians, but he did not want to displease the Loyalists. Finally, in consultation with Governor Haldimand of Québec, Governor Parr decided to resettle the Acadians in the upper St. John Valley. Here they could protect the postal routes and safeguard travelers. He confiscated the Acadians' farms and gave them to the Loyalists.

Thus began the Second Deportation for these Acadians.

Fortunately, several of the Acadians as Louis Mercure and Simon Joseph Daigle were "express carriers" and knew the upper St. John River valley. They organized twenty-four of the Acadian families being deported to petition the British government for permission to sell their current lands for the promise of two hundred acres per family in the upper St. John River valley. Once more packing their belongings, these families headed upstream, past the Grand Falls where the British could not follow in a ship to the Madawaska Territory. Within a year over half of the Acadians in the lower St. John River area would follow them. Others would resettle at Memramcook, Miramichi, Caraquet, Tracadie and Pisiquit.

The first Acadians reached the upper St. John River in June 1785 and immediately erected a large wooden cross under the leadership of Joseph Daigle at their landing site (today's St. David, Maine). This was the first Acadian Cross of the Madawaska region. Finally, after thirty years of hardship, wandering and fleeing the British, these Acadians had a permanent home. In five years the British would grant the land claims for each of the Acadian families.

Their struggle to survive, however, was far from over. The Madawaska was not a paradise - being far from any other settlements that could supply goods and having extremely harsh winters. And then there was the new American government and the old Canadian government squabbling over land and the valuable pine forests.

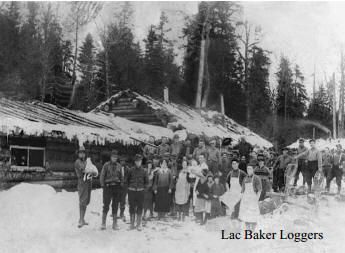

As demonstrated time and again, just because the Acadians had little formal education did not mean that they were simply farmers with no other skills. In Acadia they recovered the salt-marshes using aboiteaux. They were masterminds in the illegal trade industry in Acadia. The Acadians were innovative and very skilled craftsmen. Because of their isolation in Madawaska, they found it almost impossible to obtain trade goods for farming and household needs - so they made their tools, their homes and their boats from wood, which was abundant in Madawaska. Their woodworking skills were second to none and their homes, furniture and boats were quite sturdy and very well constructed. Their clothes came from the land - the hides of deer, caribou and moose.

Immediately after erecting the Acadian Cross, the Acadians befriended the local Malecite natives - a needed gesture to ensure their protection and survival. During the summer they selected their lands and began clearing them. Most families settled to the south of the St. John River in Maine; however, four families chose to settle across the river in Canada. Other Acadians from the lower St. John River joined these pioneers in the summer of 1786.

Their first winter was difficult with heavy snow and little food, but they survived by pooling resources and helping each other. They hunted for food and scavenged herbs and plants from the forests. In the spring of 1786 they planted their first crops, potatoes and wheat, and their harvest in the fall was good except the wheat, which they had planted too late. It suffered due to the early September frost. The small colony progressed well over the next few years with excellent harvests and significant clearing of the land. Spring floods, however, threatened the original settlements; therefore, the Acadians abandoned the low lands and moved their homes and barns to higher ground.

That first summer in 1786 Father Adrien Leclerc of Isle-Verte briefly visited the nascent colony. Overjoyed, the colonists built a primitive bark chapel in anticipation of his returning - which he did in 1787. Periodic visits from area priests continued over the next several years with Madawaska being a mission church. In November 1792 the Madawaska territory became a canonical parish and St. Basil de Madawaska became the Mother Church of Madawaska with Father Paquet as pastor.

Also, in 1787 French-Canadian emigrants from the St. Lawrence joined the Acadians in Madawaska. Thus began the dual French culture of Madawaska that endures to this day - Acadian and French-Canadian.

Until 1784 the area of New Brunswick was governed by Nova Scotia as Sudbury County. In August 1784 the Colony of New Brunswick was partitioned from Nova Scotia with its own Governor Sir Thomas Carleton. Complicating governmental affairs, Québec also claimed Madawaska creating a dual jurisdiction between the New Brunswick and Québec provinces over the territory. Before the Acadians arrived,

Québec had exercised authority in the area granting fiefs and establishing posts to protect travelers. With the arrival of the Acadians and later French-Canadians New Brunswick began exercising authority on a continual basis. The heart of the conflict stemmed from the vaguely described boundaries of this unsettled region in the early treaties.

The Acadians and French-Canadians, caught as pawns in this dispute, lived in a continual flux - never sure of their future. They actively sought to remain as part of New Brunswick. As early as 1787, Québec and New Brunswick attempted to settle the boundary dispute without success. On the sidelines the new United States was watching the dispute and already coveting the vast pine forests throughout the region. The 1783 Treaty of Paris ending the American Revolution did not clearly define the border between Maine and New Brunswick letting Maine attempt to acquire as much of the Madawaska region as it could. The intervention of Maine into the border conflict united Québec and New Brunswick against their interloper.

During this period of uncertainty the Madawaska colonists lived peaceful lives with occasional troublesome periods caused by the border conflicts. The Acadians and French Canadians lived near each other helping their neighbors and becoming one settlement. With intermarriage between the two groups the women of the families brought harmony to the settlement as they dominated the homelife.

There were, and still are to some extent, differences between the Acadians and French Canadians. The Acadians were more reserved, a bit gruffer and were easier to understand as to why they acted as they did.

They typically were more negligent in business affairs, less thrifty and tended to rely on God's Providence in their lives. They preferred verbal agreements rather than formal documents; they helped each other with their individual talents and skills and they had no fences or locks on their property. The Acadians tended to be more wary and less out-going - waiting for their neighbor to come to them. They were pessimistic, always seeing issues in the most unfavorable light and, while not being dishonest, seldom answered questions in a simple, straightforward manner. Their word, however, was their contract and once given, was not broken.

The French Canadians were honest, but not as scrupulous about their given word. They had more education and seemed to have more initiative. Unlike the Acadians, they liked to lock everything. The French Canadians managed their work in a more orderly fashion and were more formal in their relations with the Acadians. They were a jovial people.

Because of their isolation, the Acadians and French Canadians alike relied on their word as their contract. It had the force of law. The greatest insult a man could receive was that he had "lost his word".

The early years in Madawaska offered many challenges to the new colonists - land had to be cleared, crops planted and harvested, floods overcome, harsh winters survived, all necessities of life made from the resources of the land. The Acadians and French Canadians were hardy people and initially thrived in the new region; however, the floods and early frosts of 1795 and 1796 almost entirely destroyed their crops. Compounding their problems, the winter of 1796-1797 was the worst they had experienced. To survive, they had to hunt and scrape for whatever herbs and plants they could find in the forests and surrounding lands. They slaughtered their milk cows and ate what little food from crops that they had before winter was over. Only by coming together as a community, sharing what each had and the heroic, charitable work of Tante Blanche , Marguerite-Blanche Thibodeau (wife of Joseph Cyr), did the people survive. Tante Blanche on snowshoes trudged from home to home, dragging her heavy load of clothes and bits of food that came from herself and the charity of others. Rich or poor did not matter - Tante Blanche visited all sharing her "treasure" and bringing hope to the desperate. She helped bury the dead and save the weak and infirm. The sight of Tante Blanche raised the morale of the discouraged. Eventually as the spring thaws came, life improved and the settlement survived. Since that terrible winter in 1797, the Madawaska people have venerated Tante Blanche. When she died in 1810, they buried her in the church at St-Basil - an unprecedented honor for an unselfish hero of her people.

As the boundary dispute between Maine and Canada heated up, the colonists became more involved. Because the vast interior of the Madawaska region had not been explored in 1783 when the Treaty of Paris was signed, the language for the border in this area was unclear. Over the ensuing years several commissions attempted to resolve the disputes - always unacceptable to one side or the other. In the interim in 1838 Canadian lumberjacks entered the disputed Aroostook region of Madawaska and began cutting timber. Maine responded by sending an agent to expel them. The lumberjacks seized the agent. Thus began the "Aroostook War". Militias were called out by Maine and New Brunswick. Colonists took sides - often depending on which side of the St. John River they resided.

Finally, President Martin Van Buren sent General Winfield Scott to the "war zone" and in March 1839 he negotiated an agreement to avert any fighting.

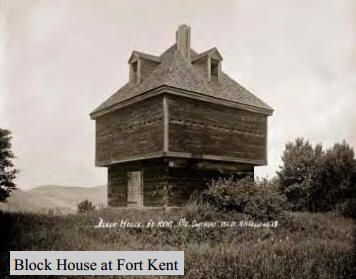

Both sides agreed to let a boundary commission resolve the dispute. In 1842 the Webster-Ashburton Treaty ended the boundary dispute between Maine and New Brunwick and established the boundary we have today - a border that runs through the middle of the St. John River to the confluence of the St. Francis River and then up the St. Francis. This effectively split the Madawaska Acadian community into two - one community separated by an international border. The only trace of the bloodless "Aroostoock War" that remains today is the Block House at Fort Kent.

Today the Acadian community of Madawaska thrives on both sides of the border. Bilingual with over 83% speaking French at home, the Madawaska people have maintained their culture it each summer at the Madawaska Acadian Festival.

References

- Albert, Rev. Thomas; L'Histoire du Madawaska (Imprimerie Franciscaine Missionnaire; Québec, Canada; 1920)

- Albert, Rev. Thomas; The History of Madawaska (Translated by Franics Doucette and Therese Doucette) (Madawaska Historical Society; Madawaska, ME; 1989)

- Collins, Rev. Charles W.; The Acadians of Madawaska, Maine - England Catholic Historical Society Publications, No. 3 (Press of Thomas A. Whalen & Co.; Boston, MA; 1902)

- Doty, C. Stewart; Acadian Hard Times - The Farm Security Administration in Maine's St. John Valley, 1940-1943 (University of Maine Press; Orono, ME; 1991)

- Gagnon, Chip; "The Upper St. John Valley - A History of the Communities and People" (This is an excellent website for the Madawaska region, its history and people) http://www.upperstjohn.com/

- Melvin, Charlotte I. Enentine; Madawaska - A Chapter in Maine-New Brunswick Relations (St. John Valley Publishing Co.; Madawaska, ME; 1975)

- Michaud, Scott; "History of the Madawaska Acadians" (This provides a concise history of the Acadians' plight as they migrated to Madawaska) http://scott_michaud.tripod.com/Madawaska-history.html [no longer available; archived at Internet Archive ]

- Pullen, Clarence; In Fair Aroostook - Where Acadian and Scandinavia's Subtle Touch Turned A Wilderness Into A Land of Plenty (Bangor & Aroostook Railroad Company; Bangor, ME; 1902)

- U. S. Department of Interior, National Park Service, North Atlantic Region; Acadian Culture in Maine (National Park Service; Washington, D.C.; 1994) Also available on the web at: https://acim.umfk.edu/

- Violette, Lawrence A.; How the Acadians Came to Maine (Madawaska Historical Society; Madawaska, ME; 1979)