Seeking An Acadian Nation

Acadian History in Brief

In 1604, an adventurous group of French colonists settled an area that became known as Acadia (today Nova Scotia, Canada), and over the next 150 years these hardy souls endured and flourished, creating an exceptional Acadian culture in the process. They also developed an exceptional cohesiveness similar to a nationalistic identity that included the ideas of republicanism, independence, and self-rule; strong-minded ideals that eventually became the focus of the American Revolution not long thereafter. But the Acadians fell under British control in 1713, and subsequently maintained a fractious relationship with their antagonists until 1755, when they were brutally erased from their homeland, deported, exiled, and made homeless by the decade-long land grab known as Grand Dérangement, Great Upheaval, or more simply, the Deportation.

About one-third of the estimated 15,000 to 18,000 Acadians died from exposure, dehydration, starvation, or drowning when the ships deporting them capsized. Meanwhile, their homes and lands were burned or appropriated and given to the 8,000 British colonists known as the New England Planters, and to the British and Colonial American soldiers who carried out the Deportation sending the Acadians down the Atlantic coast. A British effort to assimilate them into colonial society failed against stubborn Acadian resistance. Unknown to the Acadians themselves at the time, such resistance was the first step in the creation of a new ethnicity in North America.

A hundred years before the Deportation, the Acadians were living in relative peace. Professor Amy H. Sturgis, Ph.D., author and scholar, noted that the Acadian Deportation was important for two reasons:

Firstly, it was the first European state-sponsored ethnic cleansing on the continent of North America. Acadians had created much wealth, and the British simply came along and took what they wanted by brute force.

Secondly, the Acadian Deportation marked the end of a possible alternative history where there was co-operation between the Acadians and the Native Americans. As stated by Mi'kmaq Elder Daniel N. Paul, it is generally believed that early contacts between the Acadians and the Mi'kmaq quickly grew into a mutually beneficial relationship which paved the way for the French settlers to establish themselves in Acadia without Mi'kmaq opposition. The two peoples established many social exchanges, and inter-marriages were common. Mi'kmaq children attended schools alongside Acadian children. This was in stark contrast to the British treatment of Native Americans: the natives were regarded as a people fated for conquest—and genocide.

Acadians had an economy based upon "trade, not raid." They understood they were on the border between two great powers, France and England, and took advantage by trading with both, thus becoming prosperous. Like the native Mi'kmaq, they came to recognize that they had very basic intrinsic rights, which they believed no government could take from them. According to Dr. John Mack Faragher, once neutrals, they became de facto revolutionaries ahead of their time. This small idea led to big ideas and paved the way for the American colonists to later declare independence from England in 1776. Acadians had become classical republicans: they were against any form of tyranny, whether monarchic or democratic, and stood firmly upon concepts of individual rights and the sovereignty of the people.

The ethnic cleansing was successful in that little trace of the previous owners was left upon the lands that the British confiscated, but the mass elimination of an unwanted ethnic group did not result in the erasure of the owners themselves. The Deportation instead planted the seeds of many new Acadia's in over 40 localities across several countries. Québec historian André-Carl Vachon estimates that 20 percent of the approximately 15,000 Acadians settled in Louisiana and 23 percent settled in the Province of Quebec after the Deportation. A group of 202 Acadians led by Joseph Beausoleil Broussard arrived in New Orleans, Louisiana, in 1765, and their descendants, Corinne Broussard included, saw their post-dispersal culture and identity expand and evolve into today's iconic Cajun culture. This culture is a complex mélange of historical and societal traditions affected by the experiences of the diaspora as well as the influences of many other cultures that the Acadians came in contact with in South Louisiana—Native American, African, Anglo-American, German, Italian, Scots-Irish, Polish, Jewish, Hispanic, Slovak, and Lebanese.

Clearly, the ethnic cleansing carried out against the Acadians by the British in the mid-18th century is still having ramifications in the 21st century. In 1990, the Petition for an Apology for the Acadian Deportation was filed by Warren A. Perrin against the British Crown, resulting in Queen Elizabeth II granting the Royal Proclamation on December 9, 2003. Further, the proclamation designated the 28th day of July—the day the Deportation Order was signed—as an annual Day of Commemoration of the Acadian Deportation. Importantly, the proclamation, an act of contribution declared a closure of the century-long debate whether the Deportation was justified—a historical wrong was symbolically rectified.

The Struggle for World Acadian Reunification

Throughout post-Deportation history, there have been periodic attempts at reunification among the leaders of the Acadian descendants in Louisiana and the leaders of Acadian descendants in the provinces of Nova Scotia, New Brunswick, and Prince Edward Island.

The Cajuns evolved differently economically and culturally in the years following their arrival in Louisiana than did the Acadians of the Maritimes. Early on, the Cajuns' primary focus was physical survival in the wilderness of a new land. Unfortunately, this fact was not adequately appreciated by the leaders in Canada when they first sought to reach out to their Louisiana cousins in the late 19th century to try to create an international Acadian family. 1 Likewise, the Cajuns did not understand that their northern cousins were focused on survival of the French race in North America. At the time, this did not interest the Louisianans. As a result, the early efforts at some sort of tacit reunification were not very successful. Yet, persistence has paid off over the years as evidenced by the very successful first Congrès Mondial Acadien in 1994, held in New Brunswick, an event attended by thousands of Cajuns, many of whom were in Canada for the first time.

Prof. Léon Thériault used the term "Silent Survival" to describe the dark times—similar to the Middle Ages in Europe—of the hundred years that followed the Deportation. Being scattered in several countries prevented them from developing any cohesiveness. Yet, beginning slowly in the 1860s the Acadians began to seek ethnic unity and collective aspirations.

After the poem Evangeline was released in 1847, it had an immediate and profound impact upon historical and social realms. Within ten years of publication, it had been translated into 12 languages. Acadians had deeply felt generational sorrow due to the separation of families during the diaspora. The poem's central theme, the separation of a young couple, resonated with the descendants of the deportees throughout the world. In 1865, the first North American translation of the poem Evangeline into French took place in Québec City. The poem's fantastic international popularity helped to fuel the burgeoning efforts to create an "Acadian Nation."

However, up to this point, the Acadian people of Louisiana had had no contact with their northern cousins. They had influenced many other cultures in the state and developed into a distinctive part of Louisiana's diverse cultural mosaic. Acadian men and women in the Bayou State often married non-Acadian locals thus resulting in new traditions being introduced into the Cajun culture. In contrast, the Maritime Acadians remained in relative isolation, identifying more with their Quebec cousins. In New Brunswick, Acadian men could not vote until 1810. Facing economic and political discrimination, many northern Acadians migrated to New England where they worked in the factories. In 1900, Acadian leaders from Waltham, Massachusetts, formed a commission to promote their interests. It was this group of New England Acadians that began to reach out to their Acadian cousins in Louisiana in the early 1900s.

In 1880, the Société Saint Jean Baptiste of Québec held a convention and invited Acadians to attend. The next year, the first-ever national Acadian convention was held July 20, 1881, in Memramcook, New Brunswick. The 5,000 Acadians who attended discussed education, agriculture, emigration, journalism, and religion. Attendees were told in speeches that they were going to create an Acadian Nation. The second convention was held in 1884 in Prince Edward Island. The third convened in 1890 at Pointe-de-l'Église, Nova Scotia. There were no representatives from Louisiana present for these conclaves. During this period, Louisiana Cajuns were just trying to survive the postReconstruction era which ended about 1877. Although some had ascended to political power, like Sen. Robert Broussard and Congressman Edwin Broussard, the vast majority were mired in sharecropping or other menial labor like trapping, moss picking, or logging. The Louisiana Acadian upper class did not want to be considered Cajun, seeking instead to become more Americanized. They had little interest in reaching out to their Canadian cousins.

But slowly things began to change. In 1887, Québec historian Henri-Raymond Casgrain wrote about his travels in both Canada and Cajun Country where he visited with the former governor of Louisiana, Alexandre Mouton of Lafayette. Using some imagery from Evangeline, he wrote that the Cajuns were upstanding citizens—very much like Canadian Acadians. However, Harper's Weekly magazine, in a series of pejorative articles on Cajuns, wrote that they were low-class simpletons. It is suspected that opinions of visitors to Louisiana were shaped by the individual Cajuns they encountered there.

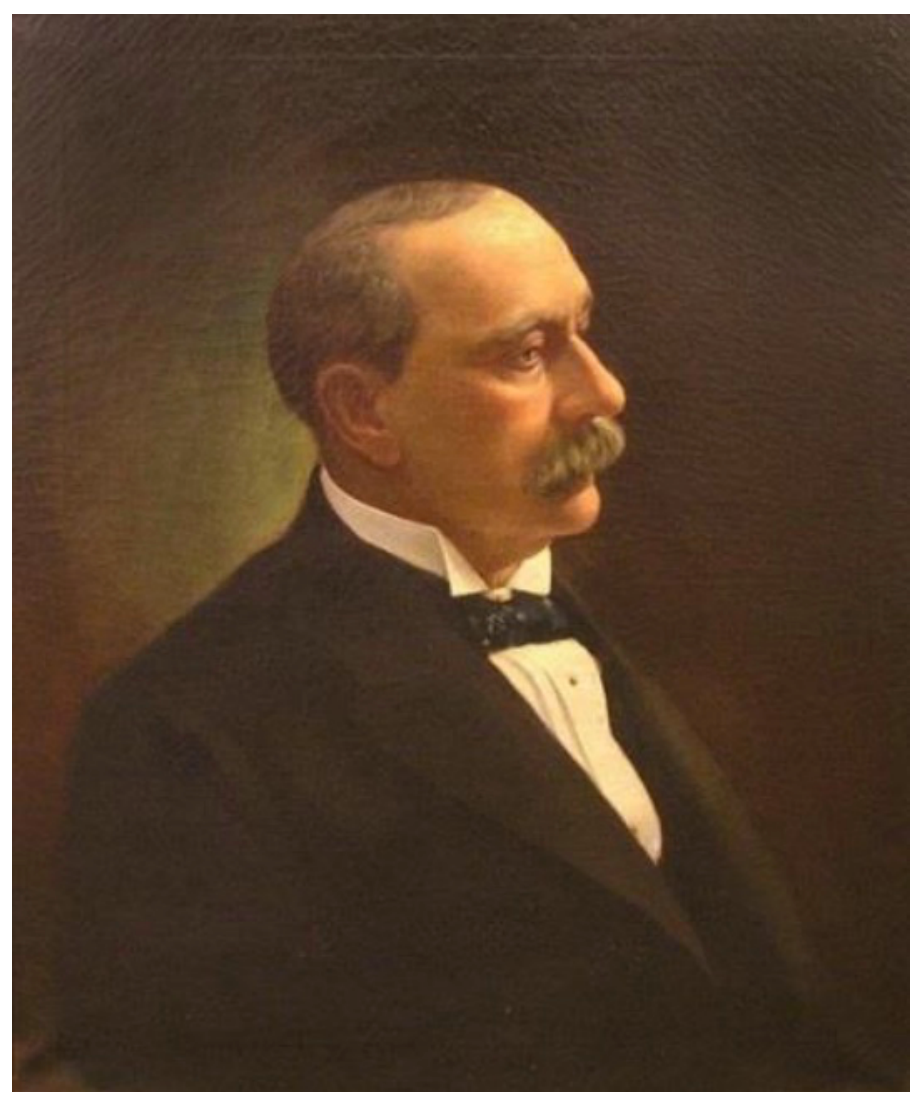

The first several national Acadian conventions—dominated by speeches seeking to show loyalty to the British Crown—were only composed of Acadians from the Maritimes. Later, they invited Acadian representatives from throughout the world. The first Cajun to finally attend a convention was Louisiana Supreme Court Justice Joseph A. Breaux (1838-1926) in 1902. 2 Breaux made a speech at the New England Congress held in Waltham, Massachusetts, where he spoke about the "baleful intentions of the British Crown." Journalists covering the speech praised the French that Breaux spoke. Following this meeting, Breaux was invited to tour the Maritimes where he made the acquaintance of many Acadian leaders. In an article written by Justice LeBlanc, "Acadians from Far and Near to Meet at Shrine," wherein it is confirmed that Justice Breaux was in contact with Acadians in the early 1900s. Breaux had fought in the Civil War and was captured by the Union Army. In 1868, after the war, he married Eugenie Mills in 1868 and they relocated to New Iberia where he set up a law practice soon after Iberia Parish was created. He was the first attorney in the parish.

Breaux participated in international conclaves in 1905, 1908, and 1910. Debates raged during these events about whether the British Crown should be held accountable for the tragedies caused ethnic cleansing brought about by the Acadian Deportation. Breaux correctly noted in speeches that most Cajuns were not concerned with those issues at that time and were more interested in being accepted as Americans, but the Canadian delegates could not understand why Cajuns did not seek to be part of the international Acadian community. But, in the end the delegates glossed over their differences and focused on their shared history, religion, language, and genealogy without exploring any serious economic or linguistic linkage.

In 1888, Breaux had become a member of the first Louisiana State Board of Education. Also on the board was renowned Tulane historian Alcée Fortier who had published numerous books on Louisiana history and the Creole language. Fortier collaborated with Breaux in firming up some semblance of a relationship between Francophones of Louisiana and Canada. In 1908, they attended the Tricentennial Commemoration of the founding of Québec, and in 1912, Fortier represented Louisiana at the North American Conference on the French Language. This helped to increase interaction between the two groups of Acadians, but again it was focused more on culture rather than language or economics.

Another major Francophone leader working closely with Breaux and Fortier in the burgeoning Acadian Renaissance was a native of St. Martinville, Louisiana, LSU Prof. Dr. James F. Broussard (1887-1942), Chair of the Department of Romance Languages. James F. Broussard co-wrote with Lucien Fournon the book Pour Parler Française (Boston, NY, and Chicago, D.C. Heath & Co., 1921) and was the author of Louisiana Creole Dialect (Kennicat Press, Port Washington, NY, 1942). In the preface of this book, he thanked the Reverend Brother Antoine Bernard, C.V.S., professor of Acadian History, "who collaborated so generously in our efforts to preserve our French folklore in Louisiana."

Broussard served as supervisor for many theses on the features of different varieties of French spoken indigenously in Louisiana. In 1934, he conceived of the idea of having a foreign language and cultural immersion dormitory on the LSU campus in Baton Rouge, Louisiana, in his efforts to help keep the French culture alive in Louisiana. On April 5, 1935, the beautiful building on Highland Road resembling a French chateau was opened by U.S. Sen. Huey Long and the visiting French Ambassador to the U.S., Andrew de Laboulaye, as part of LSU's 75th Diamond Jubilee anniversary. The extraordinary building housed 50 foreign language students who lived in 22 bedrooms—men in the north wing and women in the south wing. The building housed classes where no English could be spoken. Dr. Broussard hosted many notable guests at the house, including Émile Lauvrière, a French historian of Acadia, who resided there for two months.

According to Jean-Robert Frigault, currently working on his master's degree in history at the University of Moncton, another important person in the Acadian Renaissance was Paul Capdevielle (1841-1922) an attorney who served as mayor of New Orleans from 1900-1904. Originally of French descent, he was appointed in 1877 to the State School Board by Gov. Francis T. Nicholls. While he was a member of this body the entire state school system was reorganized to operate more efficiently. For his work in the promotion of French in Louisiana he was honored by France with the Cross of the Legion of Honor in 1902.

In the 1920s, Louisiana welcomed more Acadians from the north but without any real progress toward major joint cultural programs. In 1924, Justice Breaux hosted the former Premier of Prince Edward Island, Aubin-Edmond Arsenault, representing the Société Nationale de l'Assomption (this society later evolved into the present-day Sociéte Nationale de l'Acadie ) which had been the sponsor for all of the international Acadian conferences since 1890. Arsenault remarked in his memoir that many Cajuns appeared economically successful. This observation is not surprising since Arsenault was only introduced to the state's elite Acadians and not the petit habitants (small farmers) who constituted the vast majority of Cajuns at that time.

Justice Breaux died soon after in 1926—thus opening the door for an aggressive young politician, Sen. Dudley J. LeBlanc. When Breaux died, he left behind a historic manuscript on Acadian language and culture now known as the Breaux Manuscript. It was first put into print in 1932 by Jay Ditchy in the book Les Acadiens Louisianais et leur parler . Though the original manuscript has been lost, we still have the printed document. Most of the work is in the Cajun French language, but the section on history and folklore was transcribed into English by George Reinecke in 1966 and appeared as an article in "Early Louisiana French Life and Folklore Miscellany, V. 2."

Even after 175 years, the death and suffering caused by the Deportation remained one of the most delicate topics in Canadian politics, subject to a sustained and largely successful effort by authorities to erase it from North American history. Over the decades, LeBlanc's view of placing the blame on the wrongdoers proved to be the generally accepted version. Today, in Canada, there is an ongoing attempt to foster another even more militant version, that the Deportation should be considered a genocide. As it became clear that the Acadians of the Maritimes and their Cajun cousins would never fully comprehend the challenges each faced at home, later conclaves in the mid-20th century focused primarily on the Acadian family and a hopeful future.

In the conclusion to his book Acadian to Cajun—Transformation of a People, 1803-1877 (Jackson, Miss., University Press of Mississippi, 1992), Dr. Carl A. Brasseaux wrote: "For much of the 20th century, the Acadian/Cajun community would remain a society at war with itself as a result of the socioeconomic and cultural changes wrought during the volatile 19th century."

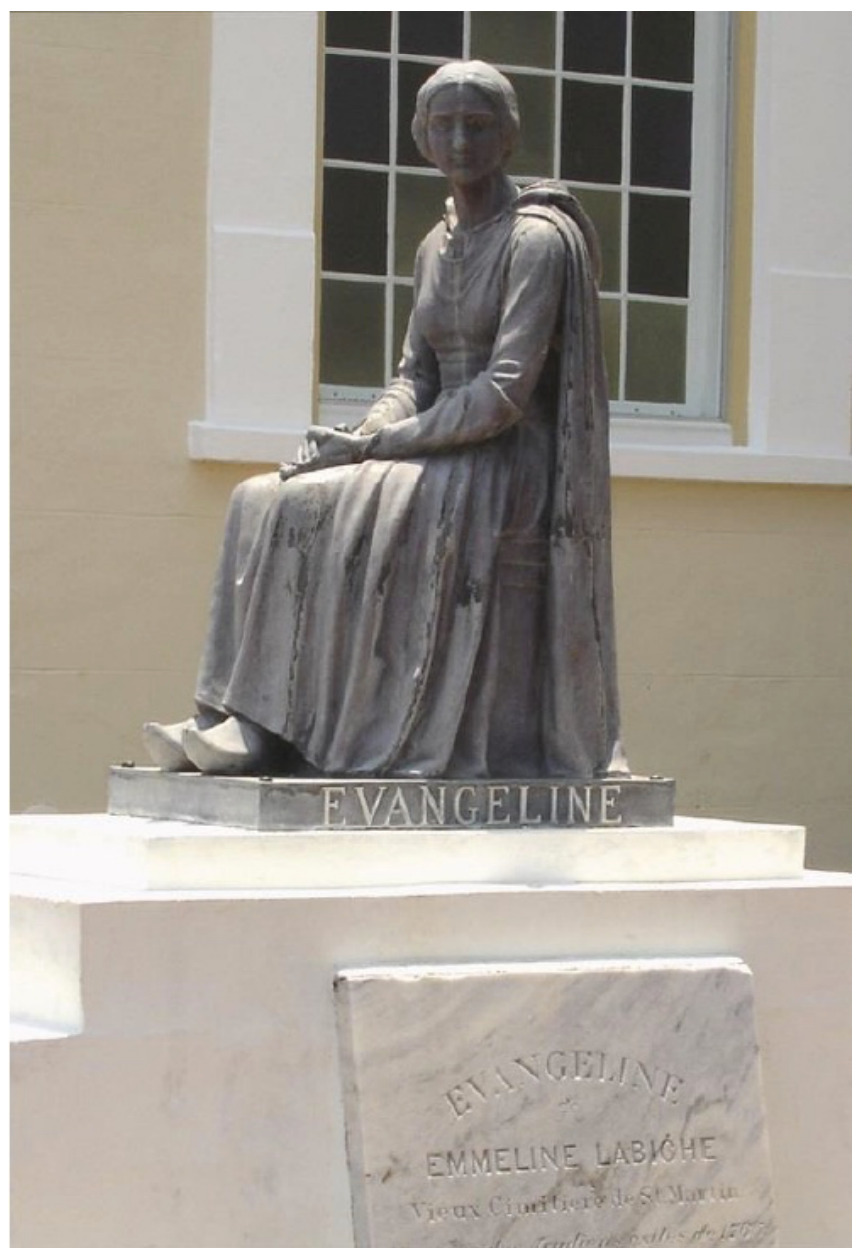

In the later part of the 1800s, the Evangeline legend had become amazingly popular in Louisiana, and the myth was adopted by businesses to sell products. In 1893, Elodie LeBlanc Broussard, a young Vermilion Parish woman skilled as a textile artist, dressed in an Acadian costume to represent Louisiana at the World's Columbian Exposition in Chicago, Illinois. In 1910, a newlyformed parish was named Evangeline. In 1928, the Longfellow-Evangeline National Memorial Association brought Evangeline Girls to the Republican and Democratic National Conventions. That same year, Dudley J. LeBlanc, now a state senator, led six delegates to an international Acadian convention in Waltham, Massachusetts. In 1929, a Hollywood production of the film Evangeline put the town of St. Martinville, Louisiana with its Evangeline monument, in the national limelight. The monument was donated by the film's star, Dolores del Rio and her film crew, and was carved in her likeness.

In 1930, LeBlanc, founder and president of The Association of Louisiana Acadians, invited young women from throughout South Louisiana to be a part of his First Official Acadian Pilgrimage of Louisiana Acadians to Grand-Pré, Nova Scotia, dressed as Evangeline Girls. He led the delegation of the girls with chaperones, Catholic priests, and prominent Louisiana businessmen to Nova Scotia, stopping at the White House on the way and meeting with Pres. Herbert Hoover.

In the 1930s, Mrs. Anasie Landry Meyers of Erath, Louisiana, became well-known for her cottonade textiles and especially for her sought-after bedspreads (courtepointe) that were gifted to First Lady Lou Hoover during this visit and later to First Lady Mamie Eisenhower. Her daughter Theresa Meyers Dronet continued the tradition. She dressed in the traditional Evangeline costume and demonstrated her skills at her spinning wheel at area fairs and festivals in Louisiana and Texas. Her husband was disabled, and thus the income from the sale of her collectible textiles was the sole support for her family. In the early 1940s, the documentary Cajuns of the Teche (1942) was filmed in the Bayou Teche area, and it included an interview and exhibition by the mother and daughter Dronet team demonstrating their skills at loom and spinning wheel. The documentary was part of the Quaint People series sponsored by the U. S. National Archives and Records Administration.

According to an article on April 16, 1931, in the New Orleans States Item , "150 Acadians arrive here to fête Evangeline's memory." The large group of French were hosted by The Association of Louisiana Acadians, founded by then-State Rep. Dudley J. LeBlanc. The highlight of the trip was the unveiling of an Evangeline statute (shown below) in St. Martinville. Louisiana, on April 19, 1931, in front of a crowd of 15,000 people. Gov. Huey P. Long delivered an address. Two of the Evangeline Girls who went on the pilgrimage in 1930 were present: Ruth Folse and Mildred Dessens (she had married and was referred to as Mrs. Emile Charles Breaux of Thibodaux, Louisiana). The bronze statue of Evangeline supposedly unveiled at this event marked the site of the "grave" of Emmaline Labiche (Emmaline was purportedly the "real" Evangeline—but she, too, was fictional and created by Judge Felix Voorhies for the book Acadian Reminiscences published in 1907. The site of the grave and statue is in the churchyard of the St. Martin de Tours Catholic Church in St. Martinville. Rev. Dismas LeBlanc of St. Joseph's University, New Brunswick, Canada, was the master of ceremonies. He was introduced by Justice Arthur T. LeBlanc of the New Brunswick Supreme Court. Marle LeBlanc of Moncton, New Brunswick, and Mrs. Laura Pitre of St. Martinville drew the veil to reveal the statute.

In 1934, with the financial assistance of $10,000 obtained from the state by Rep. LeBlanc, the first state park was established as the Longfellow-Evangeline State Commemorative Area. In 1946, as a result of LeBlanc's invitation, a group of Acadian girls from New Brunswick made a triumphant tour throughout South Louisiana. The trip was a collaboration between LeBlanc and Dr. Henri LeBlanc of Canada. They were hosted in Baton Rouge at the Governor's Mansion by Gov. Jimmy Davis. These Acadian Girls, a choral group, performed in 17 locations, including New Orleans. Group members were Alice Melanson, Maria LeBlanc, Corinne Melanson, Éméïda LeBlanc, Florence Cormier, Yvette Bernier, Léotine Poirier, Madeleine Boucher, Bernice LeBlanc, Jeannine LeBlanc, Marguerite Roy, Claudette LeBlanc, Lorraine Allain, Jeannette Malenfant, and Hélène McCarthy.

Another Vermilion Parish native French speaker played an important role in promoting the Acadian culture. In 1954, encouraged by Abbeville Mayor Roy R. Theriot Sr., Lillia Comeaux LaBauve organized Les Petit Chanteurs Acadien_ , a singing group composed of children from Abbeville schools dressed as Acadian girls and boys. Through this successful project, she kept the French folk songs alive, performing all over the state and throughout the Francophone world for 25 years. In 1955, she contributed to Les_danses_rondes, a book of old Acadian folk dances compiled by Marie del Notre Theriot and Catherine B. Blanchet. In 1970, she assisted Jeanne and Robert Gilmore, professors at the University of Southwestern Louisiana, with Chantez_en_Louisiane_ and Chantez_encore. For her lifetime of work, she was presented the Croix de Chevalier dans l'Ordre des Palmes_Académiques by France.

According to Dr. Carl A. Brasseaux, in his book In Search of Evangeline (Blue Heron Press, 1988), when Sen. Dudley J. LeBlanc led a "large number of Acadians from southwest Louisiana" [in 1930] including the Evangeline Girls to Grand-Pré, Nova Scotia, for the 175th anniversary celebration of the Acadians' exile, the southern pilgrims were received with extraordinary warmth. The group leaders exercised unprecedented influence in the inner councils of the Acadian Association." After this and 40 more years of work promoting the Acadian culture, LeBlanc became the leader in Louisiana in reuniting the Acadias of the world.

Carolynn McNally, in her article cited above, noted that the northern and southern Acadian leaders had sporadic meetings from 1902 to 1955, but these did not lead to any active or tangible partnerships between the groups, to wit: "The meeting of 'long lost cousins' was a happy ending 'to a long tragedy,' or a celebrated family reunion symbolic of a peaceful future." The support for this statement is found in the fact that today Acadians maintain their symbolic "Acadian Nation" via the celebration of their Congrès Mondial Acadien, a large festival of Acadian and Cajun culture and history.

Footnotes

- The most scholarly article on this subject was written by Carolynn McNally, "Acadian Leaders and Louisiana, 1902-1955, published in Acadiensis, Journal of the History of the Atlantic Region , in 2016.

- An article written by Justice LeBlanc "Acadians from Far and Near to Meet at Shrine," confirmed that Justice Breaux was in contact with Acadians in the early 1900s.